- Home

- News

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- World Cup 2023

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Premium

- Science

- Brand studio

- Home

- NewsNews

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Sports

- Loading...

Sports - Features

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium

Special needs: How parents are coming to their own aid

When her two-year-old son was diagnosed with autism, Radhika was in a state of shock and denial. “Why me?” she kept asking herself. After several rounds of consultation with child psychiatrists and neurologists, she decided that brooding over the situation wouldn’t help. Instead, she began meeting parents of other children with autism. After enrolling her son at a special...

When her two-year-old son was diagnosed with autism, Radhika was in a state of shock and denial. “Why me?” she kept asking herself.

After several rounds of consultation with child psychiatrists and neurologists, she decided that brooding over the situation wouldn’t help. Instead, she began meeting parents of other children with autism. After enrolling her son at a special school, Radhika took up a training programme for parents to understand more about the condition.

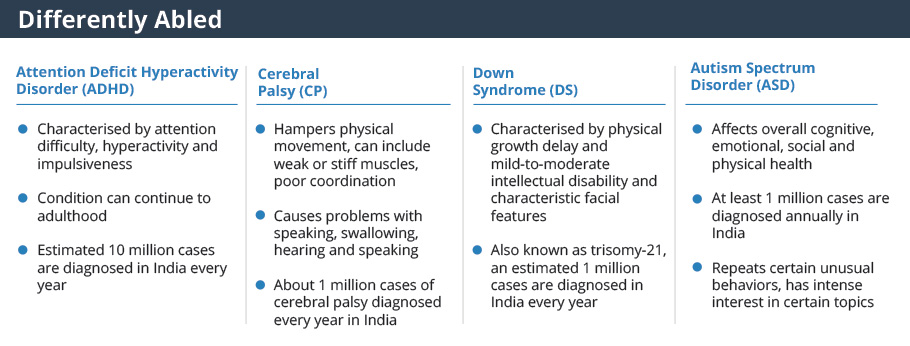

A condition that still continues to be mistaken for mental retardation, autism or autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a broad range of conditions, which hampers social skills, causes repetitive behaviour apart from affecting speech and non verbal communication.

Parenting a child with a disability is often a challenge, and can send parents into a tizzy. But, as Radhika says, learning about it and educating herself on the needs of her child has taught her a lot. “From what his actions mean to how to manage his behaviour, I have been observing ways to apply intervention, watching special educators.”

Now, Radhika says, she is a lot more patient and forgiving of herself.

Apart from ASD, a developmental disorder, there are conditions such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), cerebral palsy — another group of conditions that affects body movement — and Down Syndrome (DS), a genetic condition that causes both development and intellectual disabilities.

While Down Syndrome can be diagnosed even before birth, other conditions may take a few years to be spotted. Therefore, a parent is not quite ready to cope with the needs when they learn about the condition. Experts agree that there is no end to the struggles of parents.

Kalpana Rao, mother of a child with cerebral palsy, says that a teacher’s perspective of taking care of a child with special needs, apart from connecting at the emotional level, helped her go to the next level.

“As a mother I would be happy if my daughter accomplished a task, say, keeping her things in place. But a special educator wants her to do it consistently, focusing on improving the quality of life. I could get that perspective only as a volunteer at a special school,” says Rao.

Special needs and education

While there is little data about the estimated population with such conditions, about 2.21 per cent of the total population comprises people with disabilities. These include persons who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments, as per the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UN CRPD).

For that population, there is a need for 15 lakh special educators, and at the moment, a good number of those with special needs drop out of school after primary level, as their needs are not met.

Amid such a scenario, there are a group of parents taking up special education for many reasons — from understanding the condition of their children better to offering their services to others by working as special educators or starting their own institutions.

But do all parents know about it? Not really.

From occupational therapy, which involves enhancing cognitive and motor skills to speech therapy to physical therapy, there is a broad range of intervention offered by special schools and therapy centres. Yet, parents are in the dark about what to do at home.

Recognising the need to bring the parents on board, a few months ago, the Kerala government came up with draft guidelines that will come into effect from 2020. These guidelines not just aim at regulating centres, but also to empower parents.

According to Seema Lal, researcher and co-founder of ‘Together We Can’, a movement that brought about the guidelines, knowledge is crucial for parents. “After a child is diagnosed with a particular condition, parents often feel they are not equipped to handle the situation. This thought makes them vulnerable. What are they supposed to do once the therapy centres are done giving them the intervention they need? And how do they manage at home? Therapy centres do very little to address such doubts,” she says.

Parents donning the role of a special educator can help them immensely, she adds. “However, it should be a matter of choice, not compulsion.”

V Jayanthini, a child psychiatrist, believes that parents empowering themselves helps improve services offered to kids with special needs. She adds that irrespective of how educated a parent is, they need to know what the children are coping with and the role parents can play.

Also read: Kerala shows the way with guidelines for special needs’ therapy centres

Although a lot has changed in the last few decades, Jayanthini feels there is a lot more to be done. As most of these services for children are restricted to urban centres, there is a considerable strain on parents as they have to migrate to places near these centres to access the services.

“Still there is no regulatory mechanism that would also help the centres. They must have records and proof of meeting the necessary requirements, like in western countries where there is a framework that dictates the desired therapist-children ratio, space, first-aid needs, facilities and equipment, etc,” says Jayanthini.

Care and self-care

Senthamizhselvi, a parent of a child with special needs who now runs Kumaran Special School in North Chennai, calls the experience she gathered as an assistant to a special educator an eye-opener. “I watched the way the person handled children with different conditions with ease, but at the same time, keeping in mind their individual needs,” she says.

“It was during that stint that I gained more confidence and clarity to handle my child’s behaviour.”

Pursuing a diploma in special education for a year, she sat through classes in other schools to observe case studies of children in a module of the course that had a combination of theory and practical elements.

Some of the diplomas in special education for various conditions are recognised by the Rehabilitation Council of India. The BEd in special education (multiple disabilities) in Vidya Sagar launched last year aims to equip persons with the knowledge to help children avoid dropping out of schools due to absence of specialised staff. The course is affiliated to the Tamil Nadu Teacher Education University and recognised by the Rehabilitation Council of India.

Poonam Natarajan, founder and board member of the 34-year-old organisation and former chairperson of the National Trust, says, “When I started Vidya Sagar, the first programme I launched was the parent training programme. Having been a parent of a special child, I know how important it is to know more about the condition. Back then, there was barely any information.”

According to Natarajan, it is only because of parents of special kids who came forward to train that there are adequate staff at the institute today. “The BEd course would have had more takers if it were for a year. Now, the course duration has gone up to two years and there are not enough people willing to take it up. In the current batch of eight people, four are parents of children with special needs.”

Also read: ‘Draft education policy neglects needs of disabled children’

Besides, special schools have their own tailor-made courses for parents. Jaya Krishnaswamy of Madhuram Narayanan Centre for Children with Exceptional Needs says the early intervention programme for parents focuses on the mother as an educator of her child. She is guided by experts to evolve as a carryover agent, co-educator and a co-therapist for her child. In many cases, the father, grandparents and close relatives of the child are also involved in the process.

But in the entire process, parents need to take care of themselves too. Lotus Foundation in Chennai has a programme where the parent is made to focus on self-care, knowing the condition of the child, knowing the child, and managing the child’s behaviour.

“It is a must for parents to take care of themselves first. Healthy eating habits, good sleep, a healthy lifestyle are important. Meditation and yoga are encouraged for physical and spiritual well-being.”

Personal experience

Thirty years ago, Surekha Ramachandran set out on a journey to help children with Down Syndrome after her daughter was born with the condition. Her efforts led to the establishment of the Down Syndrome Federation of India.

“Besides early intervention, there is counselling for distraught families, training children to overcome their shortcomings, providing physiotherapy, and speech therapy, and spreading awareness about Down Syndrome,” she says.

A similar effort in Kochi provides a 10-day programme every year for parents of children with autism by Autism Club, guided by Dr CP Abobacker.

Biju Isaac, who has been associated with the club as a parent, says, “The reality of autism and various strategies to manage children with autism were explained in these classes. Often parents are left grappling with limited access to useful information.”

The club also comes up with a quarterly magazine called Autism Voice that talks, among things, about the rights of persons with autism and fight against all discrimination.

B Sriram, who published a book, Avalakku Endru Ore Manam, Aishy’s Jottings, (roughly translated as ‘A Mind of Her Own’) with the diary entries of his daughter Aishwarya, an autistic person, says, “There are many parents who look for information to understand the condition better. Many of the books they come across can discourage them immensely. I feel my book can give them a better insight.”