- Home

- News

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- World Cup 2023

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Premium

- Science

- Brand studio

- Home

- NewsNews

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Sports

- Loading...

Sports - Features

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium

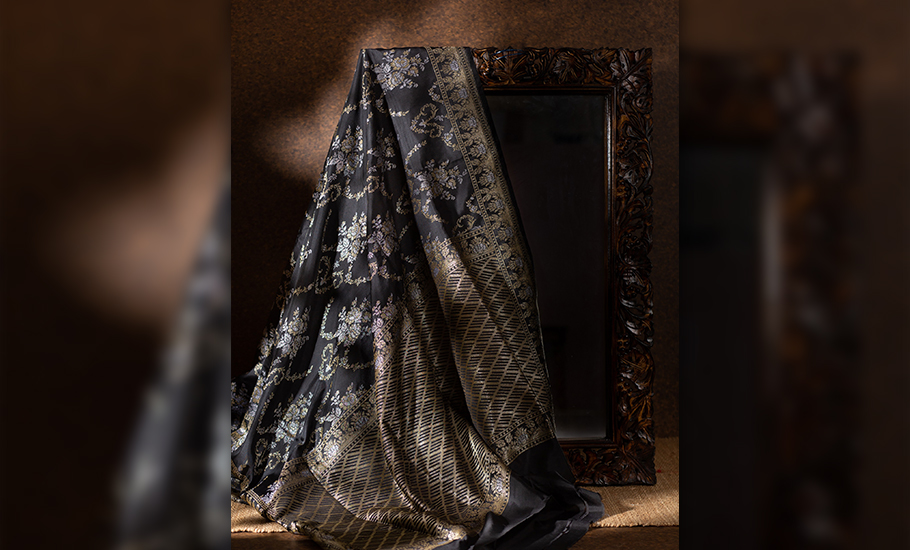

Reviving Banarasis: The warp and the weft of timelessness

Textiles, embroideries, and weaves are the fabric of Indian culture. They are the dreams, aspirations, and hopes of those who weave them — the karigars. How many times did you marvel at your grandmother’s or mother’s heavy zari Banarasis? Gently running your fingers over the intricate work? Looking wistfully in the mirror at the resplendent sheen the weave casts as you hold the...

Textiles, embroideries, and weaves are the fabric of Indian culture. They are the dreams, aspirations, and hopes of those who weave them — the karigars. How many times did you marvel at your grandmother’s or mother’s heavy zari Banarasis? Gently running your fingers over the intricate work? Looking wistfully in the mirror at the resplendent sheen the weave casts as you hold the dreamy material against your face?

There is something about the timeless elegance of Banarasis. An “object of permanence” is what textile revivalist Smriti Morarka calls it. She has been engaged in preserving weaving traditions for the past two decades and more. A Banarasi is an experience in itself, she believes. And why not? Unless you feel the touch of the glorious texture against your skin, unless you understand the quiet caress of the heavy drape, unless you are awestruck by the minute beauty of the motifs and the subtle shine of the zari work… how will you know the importance of the weave that demands to be preserved and is a legacy unto itself?

Banarasi, one of the most diverse and versatile weaves of India, is seeing a revival now. A Banarasi can be woven on silk, cotton, organza, tussar or georgette. It can also be woven in many techniques such as kadwa, jaamdani, phekwa, tanchoi, meenakari and a few more kinds.

“The advent of the Mughals in the 14th century led to a shift in the weaving industry of northern India, especially near Agra. The weavers of then Uttar Pradesh would make clothes from cotton, but the Mughal influence focused on the inclusion of silk weaving which paved the way for the thriving silk industry we see today. Varanasi (then Banaras) is credited to be the birthplace of the famous and treasured Banarasi silk sari,” say designer duo Swati and Sunaina GOLD.

The duo came together in 2007 in then Calcutta with a conviction to bring back the lost treasures of Indian woven textiles and offer them to a discerning audience that truly appreciates the craft and the effort of master craftsmen who devote their lives to weave these heirlooms and keep the art alive.

There was a time, not long ago, when most bride trousseaus boasted a few Banrasis. And, of course, the wedding sari was undoubtedly a crimson Banarsai—this was long before the likes of Sabyasachi Mukherjee made pastel lehengas much desired. The demand for Banarasis suffered with the turn of the century.

One of the reasons that led to the decline of the Banarasi weave was that there were hardly any skilled craftsmen left. With the advent of machine looms and mass production, no one had the time and patience for a handcrafted weave. The younger generation—lured by urban India and its dreams — did not take after their parents in the traditional profession of weaving. And if they did, they did not carry forward the legacy of their forefathers and lost the beauty of tradition to time and modernity. Also, the craftsmen — ingrained in their age-old design motifs and colour palettes — failed to realise that the market had changed. Maroons, reds and pinks with heavy zari work were no longer in demand. The millennials craved something that was more contemporary. Since the karigars were not reinventing themselves, patrons began losing interest. After all, it seemed if you had seen one Banarasi, you had seen them all.

It was during this phase that revivalists stepped into the picture. They aimed at protecting the expressions of weaving culture and developing new varieties that would seamlessly blend the techniques of the esteemed old and the cutting-edge new. With this aim in mind, they helped to revive and recreate the old motifs and techniques used in the antique pieces which were forgotten in time. At the same time, contemporising tradition was the key to all they did.

Organisations such as design label Prastuti, began the movement by employing more than 1,000 women karigars from rural India. Stitching together a legacy of women empowerment, the brand — spearheaded by brother-sister duo Tanvi and Anshul Gupta — went back to the basics. It shied away from using any modern technology or techniques. It can take over a year for a product to move from the design board to their store — from explaining the details/design to the weaver, getting the raw material, selection of colours and embroidery style. “Our products are heirloom pieces. Due to the extreme skill and efficiency involved, the products never go out of fashion,” says the duo.

Then there is Ekaya Banaras — India’s first handloom luxury brand that presents some of the finest Banarasis from the craftsman’s repertoire. The brand headlines the principles of heritage and artisanship. It depends on traditional karigars and merges their expertise with the vision of designers to provide a new and fresh product range that stresses luxury and timelessness. “We try to bridge the gap between the weavers and the global market,” says CEO Palak Shah. Versatility is at the core of the brand. As part of their Revival project, the brand began studying old heirloom saris of their patrons for adaptation and revival. The project is a private collaboration with each client where the brand examines old woven heirlooms to help preserve, restore and revive the delicate pieces and the cherished memories they hold.

Among the new names in the revivalist space, there is Tilfi which passionately believes in the promise, beauty and enduring legacy of Banaras’ textile heritage. Inspired to return to their roots by one of their weavers, Tilfi was started with the aim of building a global, yet resolutely Indian artisanal luxury brand. It began with the conviction that Varanasi’s craftsmen made some of the finest textiles available anywhere in the world. The brand believes in celebrating and preserving master craftsmanship and endeavours to create products that withstand the test of time.

While big names in the realm of fashion — Abu Jani-Sandeep Khosla, Ritu Kumar, Anita Dongre, Tarun Tahiliani — are reiterating their love for the traditional weaves such as Banarasi, there are also new names on the horizon — Suket Dhir, Raw Mango, Payal Khandwala and more — that are crafting a new design vocabulary when it comes to Banarasi weaves. Artisanal and handmade are their calling cards.

As Khushi Shah, founder, Shanti Banaras, aptly puts it, “A true Banarasi is a bespoke legacy. It is a cherished family heirloom of emotional value to be passed down from one generation to the next.”