- Home

- News

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- World Cup 2023

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Premium

- Science

- Brand studio

- Home

- NewsNews

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Sports

- Loading...

Sports - Features

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium

Paying for NYAY scheme: The painless way

In the run up to the Lok Sabha elections 2019, the Indian National Congress has announced a flagship scheme to uplift the economically weaker sections (EWS). Under the Nyuntam Aay Yojana (NYAY), the Congress has promised to give ₹72,000 annually to the poorest 20% of Indian families. The announcement has triggered a discussion on whether such schemes would benefit the targeted households and...

In the run up to the Lok Sabha elections 2019, the Indian National Congress has announced a flagship scheme to uplift the economically weaker sections (EWS). Under the Nyuntam Aay Yojana (NYAY), the Congress has promised to give ₹72,000 annually to the poorest 20% of Indian families.

The announcement has triggered a discussion on whether such schemes would benefit the targeted households and if yes, the number of households it would benefit. Implementing the minimum guarantee scheme would benefit 33% of Indian households (approximately 250 million people) and cost Rs 2.9 lakh crores, which is about 1.3% of the GDP, according to a study by “The World Inequality Lab,” a research organisation. The important question, however, is where will the government get money to fund such a scheme?

Congress sources say the programme will be implemented in phases, likely over five years, starting with the poorest sections. In that time, the economy itself would grow, possibly double, and tax buoyancy would reduce any shock that may be caused to deficits. The cash dose may subsume some of the subsidies in place, too, thus reducing expenditure. An obvious first step would be raising taxes.

Where will the government get money to fund such a scheme?

Experts talk of levying additional taxes on the richest 1% in India. India’s top 1% of the population holds 51.53% of the national wealth, while the richest 10% holds 77.4% of the total national wealth, as per a 2019 study by Oxfam.

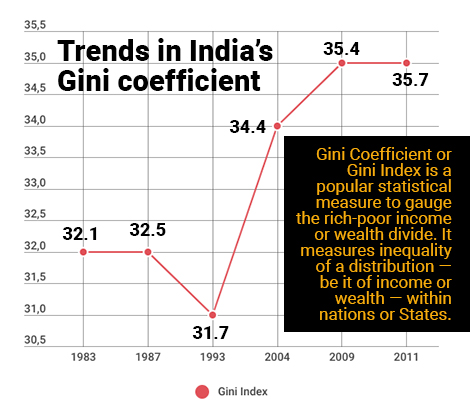

Renowned economists Lucas Chancel and Thomas Piketty have claimed that India is now seeing its highest income inequality since 1922 – the year the Income Tax Act was passed. Income inequality is defined as the tax amount being paid by the top 1% of the highest income earners.

The top 1% of the income earners contribute 22% of the total economy’s income. It is important to note that just 0.1% (approximately 13 lakh people) of the top 1% income earners accounted for 12% of India’s total income, as the economists point out in their report titled ‘Indian income inequality, 1922-2014, from British Raj to Billionaire Raj?’.

Will levying direct tax on the richest 1% income earners work?

Piketty’s report indicates high gradation in income earned by the richest 1%. Thus, levying a wealth tax on just 0.1% (or 13 lakh people) of the richest 1% of the income earners may be more appropriate.

Owing to the sky-scraping inequality and the present need to give relief to economically weaker sections (EWS) of the society, India may have to bring back wealth tax, which was scrapped by the NDA coalition government in 2015.

“Given the huge inequality created in the past 30 years, benefits have gone to the better-off sections in the society. Thus, everyone is now talking about universal basic income (or income guarantee scheme) because people from economically weaker sections are facing a crisis,” Arun Kumar, a leading economist and former professor of JNU, said.

What is wealth tax?

Wealth-tax, first put in place in 1957, is a separate tax, in addition to income and service tax. This tax is payable by individuals, Hindu Undivided Families (HUF) and the corporate sector who own wealth worth over ₹30 lakh.

As per the Wealth Tax Act, 1957, a tax of 1% is applicable on the net wealth in excess of ₹30 lakh due on March 31 every year. The wealth, as defined in the Act, includes assets such as any building or land, motorcars, stocks, jewellery, bullion, furnitures made of precious metals and land. It also includes deemed assets — assets that do not legally belong to the assessee. Deemed assets that come under wealth tax include assets transferred to spouse or another person, as well as self acquired property that is converted as the property of the family and others. This definition seeks to tackle benami assets.

In case a person owns assets in India as well as abroad, the taxability of an asset is determined on the basis of the residential status and the location of the asset. Residential status is defined by the Income Tax Department based on the number of days/years an individual spends in India.

Wealth exempted from such a tax includes property held under trust or for charitable purpose and companies registered under section 25 of the Companies Act. Companies registered under Section 25 have charity as their motive and are not incorporated with a profit motive. In case of individual or HUF, one house or part of a house or a plot of land (not exceeding 500 sq mt) is also exempt among others.

Since India had scrapped Inheritance Tax, levied at the time of inheriting an asset, inherited assets may remain out of the ambit of wealth tax.

What are economists’ take on wealth tax?

Such a tax, while perhaps being unworkable, would counteract tendencies toward inequality, and provide additional transparency and data on wealth distribution, Piketty had argued in a 2014 study of inequality titled ‘Capital in the Twenty-First Century’.

Explaining that the implementation of the wealth tax was ineffective earlier due to the inclusion of various exemptions, Kumar said, bringing back wealth tax would raise enough funds to run income guarantee scheme. The tax, however, would be required to be made more effective by introducing state tax and gift tax, Kumar stressed.

A state tax allows states to levy additional taxes on individuals, while a gift tax applies to individuals who give anything valuable to another person.

“Wealth tax is one of the options to raise funds for NYAY,” K R Shanmugam, professor at Madras School of Economics, said. He added that the government can also redirect funds from other subsidy schemes that are not doing well to fund the schemes.

Also, considering that goods and service tax (GST) is now stabilising, the government may be better placed to fund such income guarantee schemes, Shanmugam said.

Bringing back wealth tax may be a better bet

A rough estimate suggests that if a wealth tax of 1% is levied on just 1% of the population investing in the stock market, who roughly own 80% shares, India will be able to collect about ₹6-7 lakh crores, Kumar added.

Kumar’s remark stems from the fact that the government’s spending on health and education has been declining over the past few years.

While the announcements of these schemes may well be a political strategy to gain votes ahead of the upcoming general elections, according to Kumar, an implementation of any such scheme would require ‘political will’.

“(The implementation of NYAY) is possible provided we have the will,” Kumar said.