- Home

- News

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- World Cup 2023

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Premium

- Science

- Brand studio

- Home

- NewsNews

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Sports

- Loading...

Sports - Features

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium

Novak Djokovic: The worst best champion

All other things being equal, Novak Djokovic will be tennis’ winningest men’s singles player by the time he calls time on his career. Like his two great peers and rivals, Roger Federer and Rafael Nadal, he has won an all-time high 20 Grand Slam titles; also like the Swiss ace and the Spanish matador, he has completed the career slam, winning each of the four majors at least once. At 34, he...

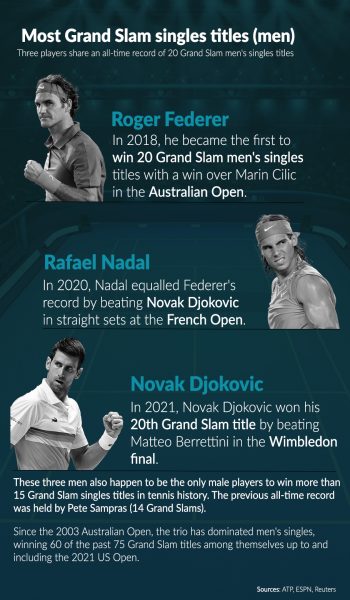

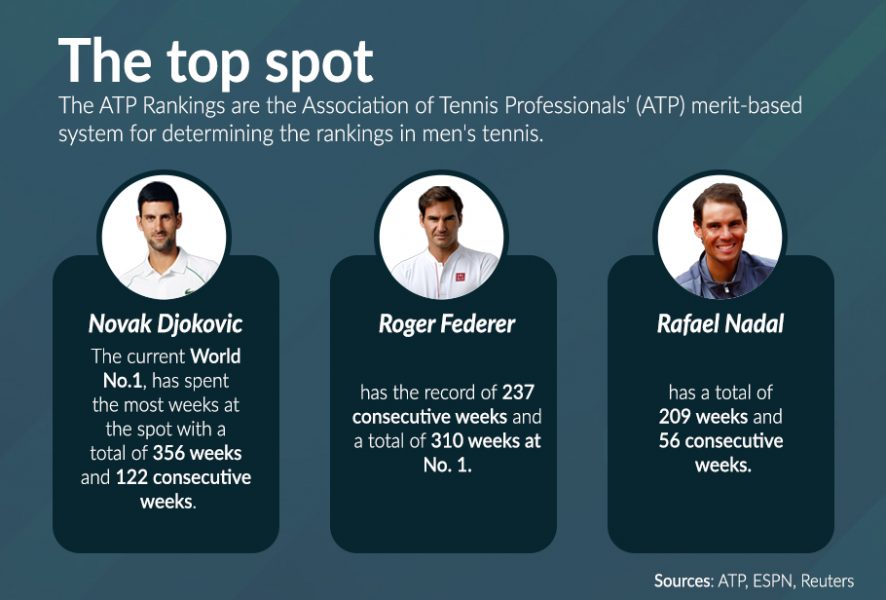

All other things being equal, Novak Djokovic will be tennis’ winningest men’s singles player by the time he calls time on his career. Like his two great peers and rivals, Roger Federer and Rafael Nadal, he has won an all-time high 20 Grand Slam titles; also like the Swiss ace and the Spanish matador, he has completed the career slam, winning each of the four majors at least once. At 34, he is the youngest, fittest and, until recently, the most active of this dream triumvirate.

Yet, Djokovic will never be the people’s champion. At least not like Federer and Nadal are. That’s bound to rankle the Serb.

It’s hard to say why Djokovic hasn’t been able to touch people across genders, nationalities and generations like his fellow members of the golden generation of men’s tennis have. After all, he has a game to die for, a spirit that’s indefatigable, a presence that is towering and inspirational. But sometimes, that’s how the cookie crumbles, doesn’t it?

As far-fetched as it might seem, Djokovic is a bit like Virat Kohli, minus the naked, all-out, in-your-face aggression. Of course, Kohli plays a team sport whereas Djokovic is in an individual pursuit of excellence. Yet, there are so many traits common to both champions – like the internal drive to be the best versions of themselves which, in their view, will also make them the best among their contemporaries. Like the willingness to put everything out in the heat of the battle, leaving nothing behind minute after minute, hour after hour, day after day. Like the understanding and the bloody-mindedness to identify and accept the need for lifestyle changes —and the maturity and passion to execute them — if they weren’t to wind up as what-might-have-beens. Oh, and like the fact that while both men are respected, admired even for their professionalism and unparalleled ambition, they haven’t always received the love they believe is their due.

It’s uncanny how both are in the news at the same time for off-field developments that have put an asterisk against their names. Kohli is no longer the captain in any format for the country, a king without a kingdom once he abdicated the T20 throne, was knocked off the ODI pedestal and dramatically stepped down as the Test skipper. Djokovic, likewise, is the lord and master of all he surveys, yet he doesn’t even have a canvas on which to paint his pretty pictures, to unleash masterpieces and continue to wow audiences who, despite not entirely warming to the person, haven’t been untouched by the magic that emanates from his racquet.

Djokovic fancies himself as something of a revolutionary, tasking himself with righting perceived wrongs that he believes he is best equipped to pull off. In his native Serbia, he can do no wrong; coming agonisingly slowly to grips with the deep psychological scars stemming from decades of internecine battles, the Serbs see in Djokovic an individual who showcases the best of themselves and their country. To them, Djokovic is a messiah, the global superstar who flies their country’s flag high in every corner of the world and yet has retained his core Serbian values despite the temptations more advanced and glamorous avenues offer.

It’s an adoration that sits lightly on the World No. 1, even if in his heart of hearts, he might feel that not even his countrymen’s deification can compensate for his elusive quest for universal love. Djokovic has come to become the symbol of Serbian pride, a torchbearer that fights the good fight and opens the eyes of the world to an otherwise speck-sized country that hardly occupies the mental bandwidth of the rest of the global populace.

The groundswell of goodwill and support in the immediacy of Djokovic’s deportation from Australia on January 16 testifies to how slighted the Serbs feel at their superhero being treated like the mere mortal he is. Djokovic knew the risk he was taking while seeking a medical exemption to play at the Australian Open, the year’s first Grand Slam, despite being unvaccinated against the coronavirus. For a man who otherwise claims to play by the rules, he did his best to bend, maybe even break, many of them until the wheels of justice caught up with him and scuttled his designs of making a strong charge for a world-leading 21st Grand Slam crown.

Djokovic isn’t a card-carrying member of the anti-vax brigade. Indeed, until he landed in Melbourne in the first week of January, he steadfastly refused to discuss his vaccination status, though it was an open secret that given his penchant for alternative medicine, he hadn’t allowed himself to be jabbed by any of the World Health Organisation-endorsed protective shields.

Australian rules are unambiguous about not allowing non-citizens or residents into the country if they are not double-dosed against the wretched virus. But a lifeline loomed ahead of Djokovic; unvaccinated players could seek medical exemption if they had contracted the virus in the weeks leading up to their arrival in Australia.

By Djokovic’s contention, he had tested positive for COVID-19 in the country of his birth on December 16, and that he hadn’t travelled to any other country in the 14 days prior to his arrival in Australia. Questions abound over the veracity of the former claim following an investigation by Der Speigel, Germany’s largest news website, while there is little doubt that the second disclosure is a complete untruth. Djokovic travelled to Spain before landing in Australia; he conveniently blamed the oversight in failing to disclose the same on ‘human error’.

After being moved to an immigration detention centre, subsequently released by a judge’s orders, having his visa cancelled for a second time by Alex Hawke, the Australian Immigration Minister, and having a second appeal overthrown by a Federal Court which automatically meant deportation, Djokovic left for Belgrade via Dubai on January 16, perhaps not with the result he had hoped for but confident he had made a statement–though what that is, is more than a little confusing.

Queering the pitch further is confirmation of the news that Djokovic holds 80 per cent stake in a Danish biotech firm, QuantBioRes, which is aiming to develop a medical treatment to counter Covid. Whether to get jabbed or not is Djokovic’s choice, obviously. But if he chooses not to, he knows the attendant risks of not playing by the rules when he seeks entry to another land. As things stand now, there is a good chance he may not be allowed into France for the French Open in May-June unless he gets vaccinated in the interim. This isn’t quite the good fight Djokovic thought he was getting into, leaving him with having to make the toughest, most morally challenging decision of his adult life.