- Home

- News

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- World Cup 2023

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Premium

- Science

- Brand studio

- Home

- NewsNews

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Sports

- Loading...

Sports - Features

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium

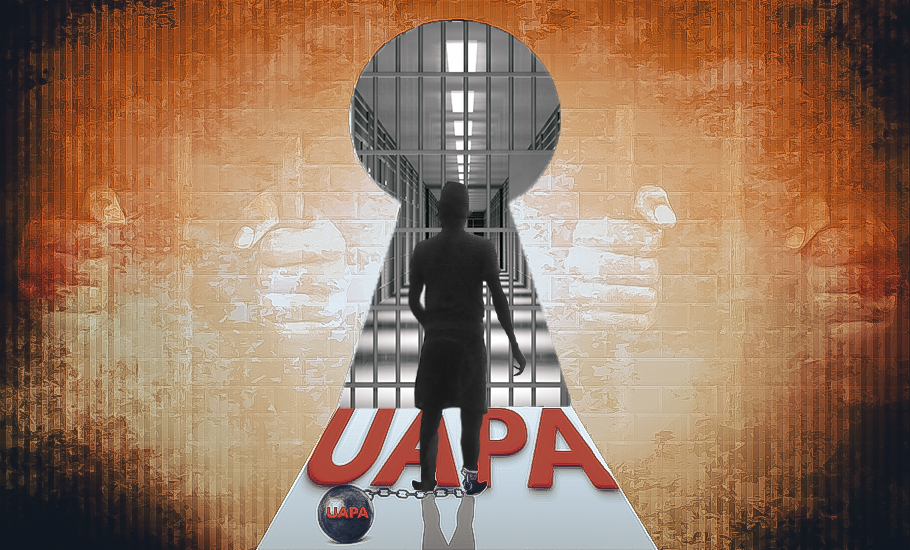

Lives put on hold, UAPA accused in Kerala stare into the abyss

Forty-six-year-old Swapnesh Babu, a construction worker in Kerala’s Ernakulam, cannot go to work all days of the week. There are days when he is required to mark his presence at the local police station and sign a register before the investigating officer to assure the authorities he hasn’t gone absconding. Swapnesh, an activist associated with the Njattuvela cultural group which...

Forty-six-year-old Swapnesh Babu, a construction worker in Kerala’s Ernakulam, cannot go to work all days of the week. There are days when he is required to mark his presence at the local police station and sign a register before the investigating officer to assure the authorities he hasn’t gone absconding.

Swapnesh, an activist associated with the Njattuvela cultural group which performs plays centred around social and political issues, was booked in 2013 under several sections of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) and the stringent Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA), 1967, also known as the anti-terror law.

In the nine years since, his case hasn’t moved beyond the FIR and his life has been stuck in the rut of regular visits to the police station and frequent police harassment.

His crime? Putting up posters along Kochi’s Marine Drive on February 21, 2013, against the arrest and the assault on activists associated with Left groups such as Porattam, an organisation of Maoist sympathisers.

Swapnesh’s was a solitary protest against the arrest of those who observed ‘Martyrdom Day’ on February 18, 2013, to commemorate the 1970 ‘encounter’ killing of Naxal leader Verghese. The Porattam activists were picked up by the Kerala Police on February 19 of that year for organising the event. Arrested for his poster protest, Swapnesh was released on bail in March the same year.

Granting bail to Swapnesh, Ernakulam sessions judge P Ubaid said, “Protesting against the government by words or slogans will not constitute a terrorist activity or any unlawful activity. We are citizens of a country where we enjoy freedom of speech and expression, of course, subject to limitations and constraints under the Constitution of India.”

The police’s case hasn’t moved an inch since but Swapnesh’s harassment has continued unabated.

“I am living in a rented house and have to move every two years. The cops keep coming and enquiring about me in my locality. Earlier, they also used to come to my worksite. This has been going on for eight years. Either they have to get me to the trial or stop this harassment,” Swapnesh, a daily wage worker, a drama artist and a social activist tells The Federal detailing his endless ordeal since being booked under the UAPA.

Swapnesh’s isn’t an isolated case. Many continue to face harassment in Kerala after being slapped with the UAPA despite no chargesheet being filed or case reaching the trial stage.

The UAPA is the primary counter-terror law in India. The law has come under sharp scrutiny recently with various courts finding application of the UAPA arbitrary.

The Act was originally enacted in 1967 under the Indira Gandhi government. But has since undergone over half-a-dozen amendments, the last one in 2019 under the Narendra Modi government. Between 1967 and 2004, the UAPA was not a terror law. In December 2004, a chapter dedicated to punishing terrorist activities was inserted. More amendments followed in 2012 and 2019 to expand the scope of the UAPA.

In its current form, the UAPA covers terrorism, money laundering for terror financing and designation of groups as well as individuals as terrorist.

The terror law makes bail difficult. It extends the pre-chargesheet custody period from 90 days to 180 days. The law curtails an accused’s to bail and makes the court depend on police documents to presume guilt. The conviction rate in the UAPA is dismal. According to the Union Home Ministry’s data given to Parliament in March 2021, only 2.2 per cent cases registered under UAPA between 2016 and 2019 resulted in conviction by courts.

Worse, the police do not even file chargesheets in such cases.

Govindankutty, the editor of People’s March, a pro-Maoist magazine was picked up by the police from his rented house in Ernakulam on December 19, 2007, over alleged Maoist connections. In addition to charges of sedition under the IPC, he was slapped with charges under the UAPA and was remanded into judicial custody for two months. While he was released on bail later, Govindankutty has been facing constant harassment from the police.

“Every time there is a VIP movement, the cops come here. They ask me about my travel plans and about the people I meet among other things. Fourteen years have passed since the FIR was lodged. They have not yet submitted the chargesheet and so there has been no trial. I face constant vigil and restrictions on my movements,” 75-year-old Govindankutty, who lives alone in a one-room house in Kochi, tells The Federal. His only means of income is the welfare pension provided by the state government. “When I started living here, the neighbours had the impression that I was a terrorist because of the frequent inquiries by the police. Now, they know there is no substance in the allegations against me. They often give me food and take care of me,” he says.

Govindankutty’s arrest followed the arrest of Malla Raja Reddy, a leader of the People’s War Group, which merged with the Maoist Communist Centre of India to form the Communist Party of India (Maoist) in 2004, from Angamaly in Ernakulam on December 17, 2007. The police intensified surveillance and search of suspected Maoists in the state which led to the arrest of Govindankutty because he was in touch with Naxal leaders and used to be a PWG member during his stay in Hyderabad in the early 1990s, besides his association with the People’s March.

The People’s March, for more than 10 years, was published from Kolkata before being shifted to Delhi. In 2003, Govidankutty shifted the publication of the magazine to Kerala. Eventually, the magazine stopped publishing hard copies but continued bringing out digital editions till 2008, the year when the website was blocked by the government. Govindankutty tried to work around the ban by publishing People’s Voice. Interestingly, the ban on People’s March was lifted in 2009. Govindankutty’s life, however, never returned to normal. He had to shut down the publication of People’s March in 2012 because of varying reasons including his health and arrests of many of the magazine’s contributors.

Thushar Nirmal Sarathy, a lawyer practising in the High Court of Kerala was arrested on January 30, 2015, under various sections of the UAPA for allegedly having connections with the banned Maoist organisations. Police crackdowns on sympathisers after major incidents executed by Maoists are a routine.

Like Govindankutty’s arrest, Thushar too was nabbed after an incident allegedly executed by Maoists. On January 29 that year, the office of the National Highways Authority of India at Kalamassery in Ernakulam was vandalised by a group of people suspected to have connections with the banned CPI(Maoist). A search was conducted at Thushar’s house in Ernakulam and the police seized books and leaflets which they said proved the lawyer’s affiliation to the banned outfit.

Thushar was an office-bearer of the People’s Human Rights Movement that was accused of being a frontal organisation of the CPI(Maoist). While no chargesheet was filed or trial conducted in Thushar’s case, surveillance and perennial inquiries continued for years.

“I surrendered my passport. I have to take the court’s approval even for travelling outside Kerala. I have been facing this harassment since seven years. Either they should submit the chargesheet and proceed with the trial or close the case,” Thushar said.

Talking to The Federal, Thushar said the case severely affected his career as well. “The cops keep warning my clients that they would not get a favourable judgment from the court if they engage me as their lawyer. As I am an accused in a UAPA case, they tell the clients that the judges would be prejudiced and they [clients] would lose the case. Not only that, in some cases, even the prosecution brings up my case to discredit my arguments in cases which are totally unrelated to mine,” Thushar says.

As many as 145 UAPA cases have been registered between May 25, 2016 and May 19, 2021. Not only has the state police filed a high number of UAPA cases, it is also clear that they invoke the Act without adhering to statutory procedures mandated under the law. While UAPA sections were included in a large number of cases, the Pinarayi Vijayan-led Left Democratic Front government has received recommendations for prosecution sanction only in eight.

As per Section 45 (1) (2) of UAPA, sanction for prosecution is given only after considering the report of an authority appointed by the Centre or the state that makes an independent review of the evidence gathered during the investigation and makes a recommendation.

The data on UAPA arrests and prosecution was revealed by Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan in the state Assembly.

Of the eight cases that received recommendations, only three were granted sanction for taking cognisance. Section 45 of the UAPA makes the sanction of the prosecution mandatory for taking cognisance of the case under the Act. Recently, the Kerala High Court quashed the charges under UAPA imposed on a suspected Maoist leader, Roopesh, on the ground that there had been a delay on part of the government in issuing the statutory sanction.

“Often, the UAPA is used to intimidate and harass people rather than proceeding with trial and bringing the case to a conclusion. In many cases, the police do not work on the case beyond filing an FIR, but use it as a weapon to keep people under surveillance,” says advocate KS Madhusoodhanan, lawyer at the high court who often appears as defence advocate for people booked under the UAPA.

The disruption in the lives of people, who have been facing UAPA charges and never got an opportunity to prove their innocence in a court of law, demonstrates the absolute misuse of such stringent laws.

“The process itself is the punishment,” an oft-repeated remark with regards to such laws is a reality that people like Govindankutty, Thushar Nirmal Sarathy, Swapnesh Babu and many others have to live with.