- Home

- News

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- World Cup 2023

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Premium

- Science

- Brand studio

- Home

- NewsNews

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Sports

- Loading...

Sports - Features

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium

How this Bengal village became the home of Iyengars from South India

Godi Bero is just a dot on the map of West Bengal. Many in the state have never heard of this picture-postcard village in Purulia district that has been a treasure-trove of history, preserving a few centuries-old cultural links between South India and Bengal. Located behind two huge rock formations some 52 kilometres from the district headquarters of Purulia, Godi Bero nestles amidst...

Godi Bero is just a dot on the map of West Bengal.

Many in the state have never heard of this picture-postcard village in Purulia district that has been a treasure-trove of history, preserving a few centuries-old cultural links between South India and Bengal.

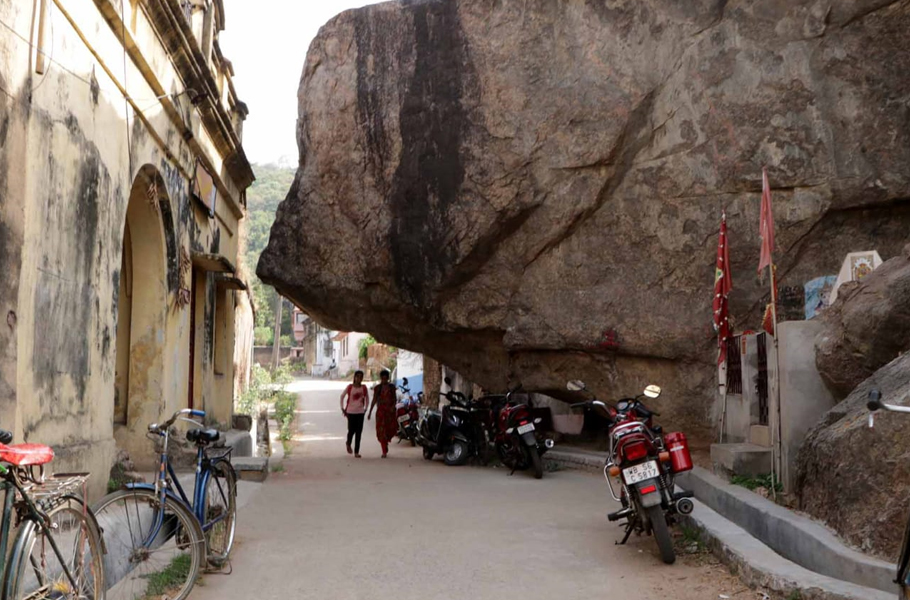

Located behind two huge rock formations some 52 kilometres from the district headquarters of Purulia, Godi Bero nestles amidst a contrasting landscape of wide expanse of barren unfertile land interspersed now and then by green wooded stretch.

At the entrance of the village the dry stretch gives away to a sprawling lake, adding serenity to the ambience. At the far end of the water body, lush green plateau provides a splendid backdrop to the place in the middle of a rough and dry terrain.

The social milieu of the village, shaped by lesser-known historical events, is as varied as its topography.

https://youtu.be/JZgDQ8iEyW0

Tamil Iyengars arrive in Bengal

Here in the middle of the 17th century some Iyengar (Vaishnavite Brahmins) families from Kanchi came to settle on the invitation of the local king.

According to legends, a revered Brahmin from Kanchi, Tiru Ranga Acharya, while returning on foot from pilgrimage to various north Indian shrines was resting on the foothills of Panchakot.

While he was mediating, cowherds saw a halo radiating around him. They reported the supernatural phenomenon to the then king of the Panchkot Raj, the dynasty of Bhumij Zamindars who ruled the western fringe areas of present-day West Bengal and some of the adjacent areas of Jharkhand in the 17th century.

The king, Satrughna Singh alias Gorur Narayan Singh, after seeing the phenomenon, pleaded with the Brahmin saint to stay in his kingdom and initiate him as his disciple, the legend thus goes.

“Tiru Ranga Acharya did not agree to the king’s proposal. But he agreed to send his brother Rangaraj to become the Raj Guru of Panchkot king,” said Trilochan Acariya Goswami, recalling the fascinating story of his ancestry he grew up hearing.

Goswami is a senior member of the now-depleted Iyengar community of Bero. Every Friday, he religiously presides over elaborate rituals such as giving baths and offering puja to local deity Sri Keshab Roy Jiu at the centuries-old Bero temple.

There is no recorded history as to when the community came to settle in this part of eastern India. As per a 1928 publication, ‘Survey and Settlement Operation’ by a settlement officer of Chotanagpur BK Gokhle, ICS, Tiru Ranga Acharya’s visit dated back to the middle of the 17th century.

“As was promised to the king, after some time Acharya’s brother Rangaraj arrived at Panchakot and initiated the king as his disciple,” Goswami added.

As per some accounts, the year of Rangaraj’s arrival in Panchkot was 1651.

After days of his arrival, Rangaraj moved his residence to the foothills of Bero as Sevait (custodian) of the deity Sri Keshab Roy Jiu of the Bero temple, according to Goswami.

The king also donated to the Vedic Brahmin 57 and ½ mouzas of Devattar state. Gradually, other family members of Rangaraj too moved to Bero, establishing a thriving Iyengar locality far away from South India.

Some Iyengar families from Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh too subsequently settled in Godi Bero. Goswami himself is a Telugu from Andhra Pradesh.

The inward migration from different parts of the erstwhile Madras Presidency continued under the patronage of the Raj Guru and the Maharaja of Panchakot until the 19th century, according to some records.

Maintaining Tamil traditions

One of the descendants of the relatively new entrants is VN Achari, a retired bank employee. For three generations, they have been living in Bero.

Clad in a white veshti (dhoti) with a tilak on his forehead, VN Achari stands out for his distinct identity in a remote Bengal village.

Most male members of the community can be seen draped in white veshti.

Despite migrating to a distant land hundreds of years ago, the Iyengar community of Bero retained their South Indian traditions, culture and language.

“The community is a strict vegetarian. We have been speaking Tamil at home since childhood. Marriage and Upanayan are still being held in South Indian traditions,” VN Achari said.

“We mostly eat South Indian food at home. But over the years some Bengali vegetarian cuisines have also crept into our kitchens,” Achari added.

Pongal and other festivals are celebrated here with as much gusto as Durga Puja, he said.

One factor that helped retain the traditional continuity is the strict practice among the community not to enter into a marital alliance with the locals.

“It was quite a feat that those days when there was no proper communication, matrimonial matches for the youth of the village were made with suitable bride and groom from place in South India through contacts maintained constantly,” said Roma Devi Achari, the 85-year-old mother of VN Achari in fluent Bengali. She is equally conversant in Tamil.

The community has by and large maintained the tradition even today, retaining regular contacts with their place of origin.

But do not they feel out of place with their dual identity?

“I feel quite at home both here and also when I visit my relatives in Tamil Nadu. This is because we have assimilated with the locals without relinquishing our own tradition, culture and language,” said Dwarkanath Achariya Goswami, 34-year-old current descendant of the Raj Guru.

Dressed in white shirt and veshti, he looks every bit Tamil.

Very few in the community, however, can read and write Tamil or any other South Indian language as there is no opportunity to pursue the language formally in school.

In Bengal, Telugu has been granted the status of one of the official languages. There are a few Telugu-medium schools in Kharagpur area in West Midnapore district. But, none in and around Bero.

“In schools we studied Bengali. We learn Tamil only at home,” VN Achari said.

Struggling to sustain

Until the 1950s and ’60s, there were around 45 to 50 Iyengar families in Bero. The number has now reduced to about 15 now, with many having migrated back to South Indian cities for better employment avenues, said Dwarkanath.

The village has a total population of about 2,956, mostly Adivasis and Bengalis.

Most of the residences of Iyengar families are today either abandoned or locked as the village has passed its prime.

Dwarkanath, an advocate by profession, is from the 14th generation of the first Sevait, Rangaraj. He is trying to retain the glorious heritage of his family. But without government support and lack of livelihood opportunities in the village, he seems to be fighting a lost cause.

After the Zamindari system was abolished, Dwarkanath’s family surrendered to the government 14,000 acres of land out of 14,050 acres it possessed.

The end of the zamindari system dwindled agricultural income of Iyengars of the village, triggering migration of educated youth for jobs.

Despite being a micro community, it contributed immensely to the development of the area, particularly in the field of education. Iyengars of the village helped establish two high schools in the area, including one for girls.

Many persons from the community have made marks in different walks of life. Prominent among them are freedom fighter S Vir Raghab Achari, former CPI (M) MP (nine-time) from Bankura Basudeb Acharia, former managing director of Sundaram Finance Srinivas Acharya, neurosurgeon Dr NK Achari, to name a few.

Iyengars of Bero are now counting their remaining days in the place their ancestors made home centuries ago.

The number of abandoned and locked houses in the locality are increasing gradually, sending across an ominous sign of an imminent end to a glorious legacy.

Financial crisis

Dwarkanath, the bespectacled current heir of the Raj Guru, is striving to retain the tradition amidst many odds.

The perpetual annuity which Dwarkanath’s family is supposed to get against the surrendered properties is pending for over 15 years, he said.

Within the debottar estate, there are eight temples and one mosque.

To maintain this heritage, which provides direct employment to 60 people, Dwarkanath regularly needs to dig deep into his pocket.

“Our estate has a mango garden, which fetches an annual income of about Rs 50,000. From an annual fair held at Chandi temple we get around Rs 60,000 and another Rs 35,000 per annum from the estate’s farm land. These incomes do not suffice the requirement. To meet the shortfall, I have to chip in. We also get some donations occasionally. Srinivas Achariya, the MD of Sundaram Finance, Chennai helped renovate Keshab temple,” he said.

The centuries-old temples in the village also stand testimony to a rich legacy of Hindu-Muslim unity.

“In this village, there are about 15 per cent Muslim population. They are the descendants of guards brought in by our ancestors to protect debottar properties, including temples from Bargi invasion,” Dwarkanath said, sharing vignettes of his family history.

Barigs were Hindu Maratha raiders who indulged in large-scale plundering in Bengal for about 10 years in 1741–1751.

Pointing at the relic of what once served as a kitchen of the Keshab temple, Dwarkanath said during the heydays of the Sevait, hundreds of people used to get free prasadam everyday.

“Tons of firewoods were used to cook prasadam for so many people. When the Nawab of Bengal (I don’t exactly remember the year and the name of the Nawab) came to know about the use of such huge quantities of wood, he ordered an inquiry. After the investigation revealed the purpose of using wood, the Nawab issued an order ensuring continuous supply of wood,” he said.

That was a different era. Today, Godi Bero has lost most of its old grandeur, but somehow managed to hold on to its unique heritage. But for how long? This is a question that weighs on the mind as one returns from the village.