- Home

- News

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- World Cup 2023

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Premium

- Science

- Brand studio

- Home

- NewsNews

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Sports

- Loading...

Sports - Features

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium

How Rajaji Tiger Reserve is roaring back to life in Uttarakhand

For the past many decades, the picturesque Rajaji Tiger Reserve in the foothills of Uttarakhand existed under the shadows of its illustrious and more popular counterpart, Corbett Tiger Reserve. While Corbett flourished on land, in poems and stories, Rajaji lagged in the competition for attention and care. Even as Rajaji began crumbling under the increasing load of human population around it...

For the past many decades, the picturesque Rajaji Tiger Reserve in the foothills of Uttarakhand existed under the shadows of its illustrious and more popular counterpart, Corbett Tiger Reserve. While Corbett flourished on land, in poems and stories, Rajaji lagged in the competition for attention and care. Even as Rajaji began crumbling under the increasing load of human population around it and in the process lost much of its tigers and other species, Corbett prospered, regularly opening its gates to visitors, including Prime Ministers, photographers and wildlife filmmakers from across the globe.

A new development has, however, begun to show results in changing the fate of Rajaji Tiger Reserve. What brought about the miracle at Rajaji Reserve are three elevated corridors built by the National Highways Authority of India (NHAI).

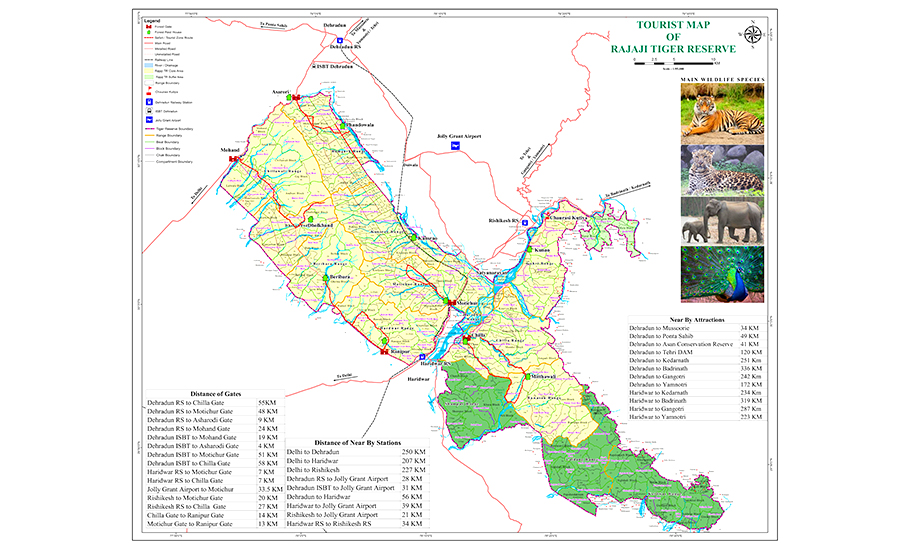

Until the mid-2022, Rajaji Tiger Reserve, comprising the western-most boundary for the tiger, the elephant and king cobra in India, was dying a slow death. Too many factors contributed to the human-induced asphyxiation. A national highway and a railway line running right through the middle of the Reserve dissected it into two parts — the western and the eastern, curtailing the movement of wildlife from one part to another. The presence of Haridwar and Rishikesh in the region, the two religious hotspots sharing their boundaries with the reserve, made it impossible for wildlife to flourish.

Such was the state of affairs that the huge western part of the reserve, which has a potential of holding 80-plus tigers, was left with just one ageing tigress. The eastern block, consisting of Chilla Range, fared somewhat better, showing an increase in the number of tigers over the years. It has around 30 big cats now. But no male tiger, or for that matter any tiger, ever crossed over from the eastern to the western block, due to the constant pressure of thousands of vehicles on the national highway.

Correct diagnosis

It was in April 2015 that Rajaji was notified as the 48th Tiger Reserve of India, and second Tiger Reserve — the first being Jim Corbett — in Uttarakhand, having inherited its name from the Rajaji Sanctuary, which was one of the constituent units that was amalgamated to create Rajaji National Park in 1983.

Rajaji Sanctuary, in turn, was named after C Rajagopalachari, popularly known as Rajaji, the first Governor General of independent India because it was on Rajagopalachari’s behest that the sanctuary was created. It is said that when Rajaji was invited for a hunting expedition to the area, he was so impressed by the biological diversity and variety of wildlife in the area that instead of hunting, he suggested the creation of a wildlife sanctuary in the area.

But despite the richness of critical wildlife, the area and the problems faced by its inhabitants due to rapid urbanization and rising tourism remained unaddressed, despite concerned authorities flagging the issues. As early as 1983, the Wildlife Institute of India (WII) prepared a research paper highlighting how the movement of elephants, tigers and other wildlife between eastern and western parts of the Rajaji Reserve was seriously restricted. In 1990, eminent wildlife expert AJT Johnsingh stressed upon the need for creating an unhindered wildlife corridor between Chilla (eastern) and Motichur (western) sections of the reserve.

But as the subsequent decade showed, all well-meaning entreaties remained buried in government files. Uttarakhand, then a newly formed state, was battling its own demons, both real and imaginary. Political one-upmanship and constant see-saw between the Congress and the BJP remained high. A tiger and an elephant do not cast votes. So, why bother about them? In a state where chief ministers change with frightening frequency, and with them the political priorities of the day, poor tigers and other wildlife of Rajaji had little scope to be considered priority.

Despite the political apathy, the forest department was hard at work, looking for solutions. “The forest department of Uttarakhand was not sitting idle. We had been evaluating the situation constantly. Various possible solutions were put on the table. It was important not to lose the Rajaji Reserve,” Samir Sinha, Uttarakhand’s principal chief conservator of forests (wildlife) and the chief wildlife warden, said.

The efforts bore fruits in late 2022, after NHAI, after prolonged consultations and brainstorming sessions with the state forest department and other interested parties, including WII, completed the construction of three elevated corridors — at Motichur, Teen Pani and Lal Tappar — between Haridwar and Dehradun.

Success — at last

And it was in October end last year that the moment which everybody was waiting for all these decades arrived. Footage from the CCTV camera installed by the forest department showed a male tiger walking underneath one of the corridors from the eastern to the western side.

“This was a huge step. It is a testimony not just to the resilience of our ecosystem, but also to what concerted human efforts can achieve,” Sinha said.

The authorities are keenly watching the area and studying the movement of other tigers. “Another tiger has crossed the Ganges from the Chilla side. We are monitoring it closely. It’s likely to cross over to the western side. The corridors have resurrected the movement of tigers and other wildlife. Now, we can safely say that it’s only a matter of time when the Rajaji Park becomes one composite whole, and not a separate island which it was until very recently,” field director of Rajaji Park, Saket Badola, told The Federal.

A few years ago, the forest authorities had translocated two tigers — a male and a female — in the western block of the reserve. The tigress has still not given birth to cubs. But both Sinha and Badola hope that once the tigers from the eastern block start coming regularly to the western side, the process of natural regeneration would start. This is what happened in Sariska and Panna tiger reserves when, after several false starts, the relocated tigers started breeding successfully in the region.

Threats to Rajaji

Having tigers back in Rajaji Park is one thing, safeguarding the forests which holds them and other wildlife is another. Badola admits there are a number of threats which are still looming over the fragile Rajaji Park ecosystem. “First is the porous landscape. The highway from the National Capital Region passes through heavily-populated Haridwar, Rishikesh and Kotwar regions, all of which share boundaries with Rajaji Park. There are industrial units in Sidkul. The waste water from here is released into Song, Suswa, Rispana and Bindal rivers flowing through the park. None of this is good news for wildlife conservation and propagation in the area,” said Badola.

The threat of poaching too looms large in the region apart from man-animal conflicts. “To address these issues, we have stepped up patrolling, made more watch towers and are even using drones for surveillance. We are also focusing more on capacity building of staff, vets and other personnel connected with wildlife preservation,” he said.

Return of tigers to the eastern zone of Chilla

In the 1990s, the Chilla range had been virtually run over by ‘Van Gujjars’, who had made umpteen settlements inside the forests. Thousands of cattle which they owned wreaked havoc on the fragile ecosystem of Rajaji Park, leading to tigers almost disappearing from Chilla range, and several herds of elephants moving out in search of food which was being consumed by the cattle reared by the nomadic community.

“It was a humungous task to peacefully move out Van Gujjars from the Chilla range of the park. The effort went on for several years, but we finally managed to achieve our goal. Thanks to this, not only has the tiger made a magnificent comeback in Chilla, but there is proportionate increase in other wildlife too,” Sinha told The Federal.

The Terai Arc and its importance

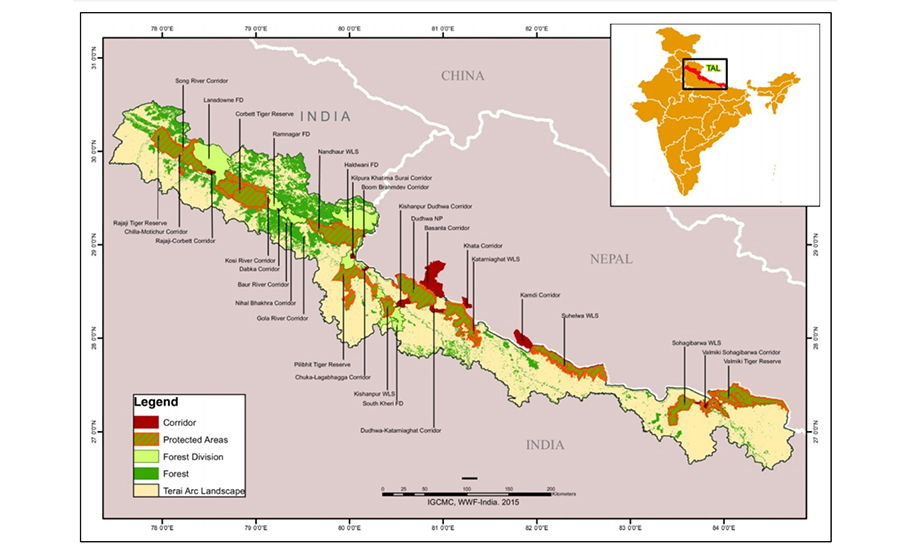

Rajaji Park forms the western-most boundary of the Terai Arc, the stretch of vast forest which starts from Uttarakhand and reaches right up to Uttar Pradesh before ending in the Valmik Tiger Reserve of Bihar. It also encompasses many regions of Nepal. Though fissures have developed at several places in the form of new settlements and towns, the basic contour of the arc remains intact. “Wildlife still moves from one region of the arc to the other,” said Badola.

Significantly, the tiger is found in almost all the reserves of Terai Arc, arguably making it one of the longest stretches of forest in all of Asia. Rajaji Tiger Reserve, Corbett Park, Dudhwa National Park, Katarniaghat Wildlife Sanctuary, Pilibhit Tiger Reserve, Suhelwa Wildlife Sanctuary and many more protected areas fall under the arc.

A strengthened Rajaji Reserve would not only make the boundary of the Terai Arc stronger, it would also give a new lease of life to the endangered wildlife and forest cover of the region.