- Home

- News

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- World Cup 2023

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Premium

- Science

- Brand studio

- Home

- NewsNews

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Sports

- Loading...

Sports - Features

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium

Why Ambedkar’s vision of Dalit consciousness stands defied

On April 14, India marked the 131st birth anniversary of Dr Bhimrao Ambedkar. Political parties, irrespective of their ideological persuasions, broke into a competitive frenzy to unveil statues of the Dalit icon and architect of the Indian Constitution, launch welfare schemes or organise seminars and events in his name. It is tempting to imagine how Babasaheb, were he alive today, would...

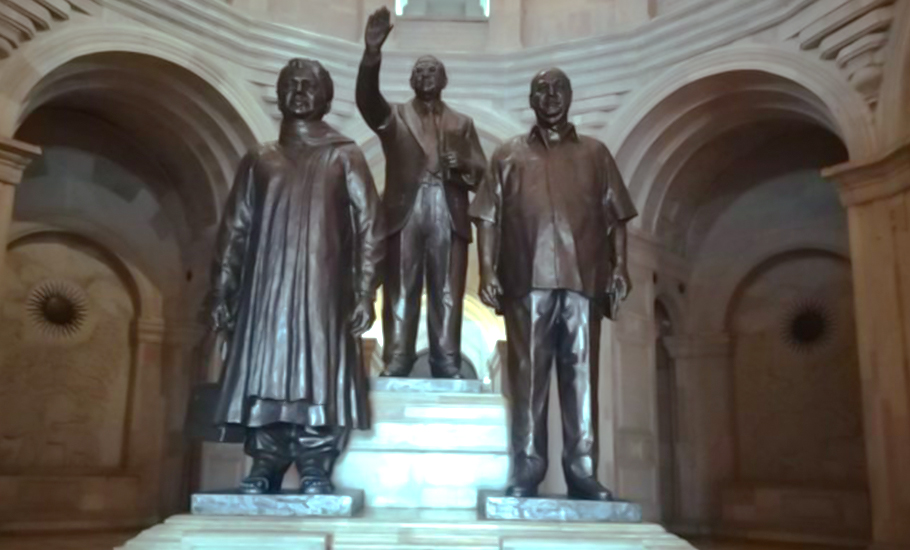

On April 14, India marked the 131st birth anniversary of Dr Bhimrao Ambedkar. Political parties, irrespective of their ideological persuasions, broke into a competitive frenzy to unveil statues of the Dalit icon and architect of the Indian Constitution, launch welfare schemes or organise seminars and events in his name.

It is tempting to imagine how Babasaheb, were he alive today, would have reacted to being elevated to a cult figure. In his final address to the Constituent Assembly on November 25, 1949, Ambedkar had warned the nation of the perils of hero-worship of even great men. “For in India, Bhakti or what may be called the path of devotion or hero-worship, plays a part in its politics unequalled in magnitude by the part it plays in the politics of any other country in the world. Bhakti in religion may be a road to the salvation of the soul. But in politics, Bhakti or hero-worship is a sure road to degradation and to eventual dictatorship,” Ambedkar had said.

In the 66 years since his untimely demise, Ambedkar has emerged as a figure all political parties – even those whose previous avatars once violently opposed the Constitution he framed and found his idea of affirmative action for emancipation of oppressed classes as abhorrent to their ideology – want to appropriate as their own.

And yet, while Ambedkar’s fan base continues to expand exponentially, his great bequest to India’s democracy – a vibrant, resilient and sometimes militant movement for the socio-political emancipation and invigoration of the Dalit – appears to have reached a precipice.

Last month, results for the UP assembly polls saw the electoral annihilation of the state’s – as also the entire Hindi heartland’s – foremost Dalit identity party, Mayawati’s Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP), as the BJP stormed back to power for a second consecutive term. Punjab, the state with the highest concentration of Dalit population across the country, voted almost uniformly for the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), an outfit that has in the past expressed reservations against reservations, has no notable Dalit face and has in its key leadership positions (chief ministers, Rajya Sabha MPs, top rung office-bearers) only members from the upper castes.

The two outcomes seem to reaffirm two distinct electoral trends that have, in the recent past, disrupted the conventional Dalit political movement and defied the Ambedkarite vision of Dalit consciousness.

The poll results in UP, a state otherwise known for its overt caste-identity politics, saw Dalit assertion being subsumed by (as also witnessed in varying degrees in the past two Lok Sabha elections and the 2017 UP polls) and homogenised into the BJP’s rabid Hindutva scheme. In Punjab, despite the Congress’s appointment of Charanjit Singh Channi as the state’s first ever Dalit Sikh CM, the AAP won over the Dalit community through its narrative of alternative politics.

What was seemingly common to the poll results in both these states was how successfully the BJP and the AAP projected a politics of aspirations to tide over hurdles that the conventional politics of identity may have posed to their respective bids for victory.

“The dynamics of contemporary Dalit politics are no longer what they used to be until the 1990s when merely flaunting Dalit identity, proclaiming adherence to Babasaheb’s vision and mouthing platitudes for social justice would mobilise the Dalit voter in favour of a party. Today, the Dalit voter wants more from a political party as his aspirations have transcended identity politics. These aspirations may simultaneously be about issues arising out of governance, as may be the case in Punjab, or the sentiment of parity with upper castes that is pushed through religious radicalisation of the Hindutva framework as has been the case in UP or other states where the BJP has successfully dominated areas of Dalit concentration,” explains Anurag Bhaskar, assistant professor at the Sonipat-based Jindal Global Law School.

K Raju, former IAS officer and national coordinator of the Congress party’s SC, OBC, Minority & Adivasi Departments, agrees with Bhaskar. India’s contemporary Dalit politics – its leadership and narrative, says Raju, is “in need of a reboot”.

Raju, who edited the recently launched book, The Dalit Truth – Battles for Realising Ambedkar’s Vision, told The Federal, “self-proclaimed Dalit identity parties like the BSP, Lok Janshakti Party or the various factions of the RPI, have failed to present any forward-looking agenda that caters to the aspirations of the Dalit community… somewhere down the line the Congress too failed to keep up with the changing dynamics of Dalit politics. The void thus created helped the BJP to spread falsities and impose an aggressive cultural and sub-cultural nationalism on the Dalits to co-opt them as foot soldiers of the violent Hindutva movement.”

While AAP is still a newbie on India’s vast political landscape and its ability to repeat Delhi and Punjab like victories in other provinces by assimilating various castes groups is still on trial, the BJP’s in-roads across various denominations (with the predictable exception of Muslims) is amply evident.

The successful integration of Dalits into the BJP’s vote bank, except in states where sub-nationalism or regional and linguistic identity politics is still dominant, has been amply visible in recent years. Take, for instance, the results of the 2019 Lok Sabha polls in which the BJP successfully swept 46 of the 84 constituencies reserved for scheduled caste candidates. Add to this tally the seats won by its regional allies such as Nitish Kumar’s Janata Dal (United), late Ram Vilas Paswan’s Lok Janshakti Party and Anupriya Patel’s Apna Dal, and the count goes up to 52 seats. A bulk of the Dalit-reserved seats that the BJP failed to win came from states of Tamil Nadu, Odisha, Punjab, Andhra Pradesh and Telangana while it picked up all or a majority of such seats in states such as UP, MP, Rajasthan, Karnataka, Gujarat, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Assam and Jharkhand.

It is not difficult to see how Ambedkar’s vision for socio-political emancipation of the Dalits through overcoming religious dogma and annihilation of caste would ideally be a formidable ideological counter to the currently raging vicious politics of Hindutva as propagated by the BJP and its ideological affiliates or subsidiaries. Yet, the BJP has been the biggest beneficiary, at least north of the Vindhyas, of the disillusion that the Dalit electorate has had against outfits such as the Congress, BSP, the Left parties or others that once found a captive vote bank in the community.

This churn, of course, didn’t happen overnight nor can it be solely attributed to the Modi mania that has had India under a self-destructive trance ever since 2014. Harish Wankhede, assistant professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University’s Centre for Political Studies, believes that the present electoral affiliation that the BJP has successfully forged with the Dalits is the result of propaganda spread through past decades by the party’s ideological mentor, the RSS. Wankhede says the RSS-BJP combine popularised “Brahmanical culture and religious artefacts as national symbols” and aggressively enlisted the community into the communal Hindutva scheme by telling Dalits that they are an “integral part of the umbrella Hindu identity”.

In his paper titled ‘Indian Dalits and Hindutva Strategies’ (Denison Journal of Religion, 2017), academician Seth Schoenhaus writes: “The possibility of inclusion in Hindutva furnishes Dalits with solidarity, as they channel their feelings of marginalisation into the popularised movement that Hindutva has become.”

Rajasthan-based Dalit rights activist Bhanwar Meghwanshi, who was once an RSS volunteer (karsevak), told The Federal that the RSS-BJP combine invested massively to enlist Dalits “primarily as foot soldiers who would swell the ranks of its mobs for carrying out riots targeted at Muslims… Sangh pracharaks would talk up Dalit pride by speaking of the community as saviours of Hindu Rashtra and misappropriate history by telling the Dalits that it was them who fought against Islamic invaders in the past alongside the Kshatriyas and it was now their duty to carry forward that legacy as the country was being overrun by Muslims.”

Meghwanshi had quit the RSS in 1992 when he “realised that the Sangh wanted us to believe we are Hindus but within its ranks it treated Dalits with the same contempt that the Varna system advocates”. In 2019, Meghwanshi wrote his memoir, I Could Not Be a Hindu: The Story of a Dalit in RSS, which detailed his time with the RSS and the discrimination he faced by the outfit’s upper caste members on account of being a Dalit.

“By assimilating Dalits into the Hindutva framework, the BJP tells the Dalit community that it has fulfilled Babasaheb’s dream of annihilation of caste but what it has actually done is to strengthen sub-castes. The RSS-BJP strategy for the past few years has been to subtly pit less dominant Dalit sub-groups against the more dominant ones and then consolidate the smaller Dalit groups behind it. Now they have begun appealing at an even lower level of gotras (sub-clan) by conducting events targeting people of specific gotras instead of castes and sub-castes. With other political parties doing nothing to expose the BJP’s hypocrisy, I don’t see any awakening among the Dalits at least in the political sphere,” Meghwanshi said.

Raju believes a bigger disservice has been done to the Dalits by political outfits that owed their rise and electoral wins to their Dalit identity. “To stay politically and electorally relevant, Dalit parties like the BSP, RPI, LJP formed alliances with the BJP despite clear ideological differences. These alliances eventually led to the Dalit parties ceding their political space to the BJP. Dalit voters felt that if the BJP is acceptable to a Mayawati, a Ramdas Athawale or a Ram Vilas Paswan, then why should Dalits treat the BJP as pariah,” said Raju.

Beyond political mobilisation, the RSS-BJP combine also invested in social campaigns for bringing Dalits under the Hindutva arch. Though never shedding their Brahmanical stamp, saffron affiliates systematically carried out sustained and extensive nationwide programmes that included community meals (samrasta bhoj), opening schools in Dalits bastis, organising Ram-leelas with the heavy symbolism of Lord Rama (the BJP’s favourite Hindu deity) being the saviour of Dalits, identifying and deifying icons of cultural and social importance to various Dalit sub-castes, etc.

These measures helped the Sangh Parivar homogenise the many distinct Dalit sub-castes into one common Hindutva meta-narrative. Ambedkar’s doctrine of annihilation of caste was based on his belief that “castes are anti-national” because they “bring about separation in social life” and “generate jealousy and antipathy between caste and caste”.

While advocating complete abolition of castes, Ambedkar had told the Constituent Assembly, “we must overcome all these difficulties if we wish to become a nation in reality. For fraternity can be a fact only when there is a nation.”

By absorbing the Dalit into its Hindutva meta-narrative, is the BJP craftily tweaking Ambedkar’s vision into a Hindu Rashtra being the prerequisite for fraternity in India?