- Home

- News

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- World Cup 2023

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Premium

- Science

- Brand studio

- Home

- NewsNews

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Sports

- Loading...

Sports - Features

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium

GM crops: How farmers are ploughing the field of frustration

‘Chor Bt nahin, hakkache Bt (Not by stealth, Bt by right).’ ‘Tantragyan swatantra amchya hakkachi, nahin kunyacha bapache (Technology freedom is our right, not anyone’s father’s).’ These are a couple of slogans farmers in Maharashtra have been raising as they fight for the right to use genetically modified (GM) crops. Unhappy with the slow pace at which the government is moving on...

‘Chor Bt nahin, hakkache Bt (Not by stealth, Bt by right).’

‘Tantragyan swatantra amchya hakkachi, nahin kunyacha bapache (Technology freedom is our right, not anyone’s father’s).’

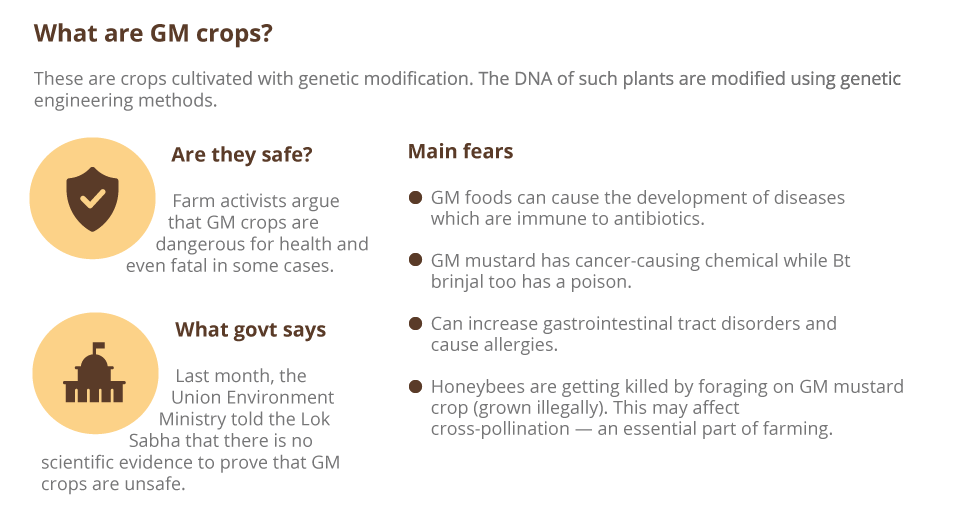

These are a couple of slogans farmers in Maharashtra have been raising as they fight for the right to use genetically modified (GM) crops. Unhappy with the slow pace at which the government is moving on the issue, some farmers affiliated with unions in Maharashtra and Haryana have taken matters into their own hands.

They planted unapproved GM crops — like cotton that is immune to the controversial weedkiller glyphosate, and brinjal that is toxic to the fruit and shoot borer — in defiance of the law. The protesters want access to agricultural biotechnology so they can lower the cost of cultivation. But there is no indication that the ruling party will overcome internal opposition and oblige them.

The protest planting of herbicide-tolerant and bollworm-resistant (HTBT) cottonseed began on June 10 at Akoli Jahangir village in Maharashtra, in the three-acre field of Lalit Patil Bahale, a microbiologist by training. He had stopped growing cotton about two decades ago, after continuously losing the crop to bollworms. That was before GM cotton with the bollworm-killing Bt trait was approved for cultivation in 2002.

The event was organised by the Shetkari Sanghatana, a 40-year-old Pune-based farmers union. Sharad Joshi, its founder, gave up a job in the United Nations at the age of 40 and came back to Pune to farm. When he realised that the government’s policies had largely made farming unprofitable, he became an advocate for free markets and free access to technology for farmers.

Court sides with farmers

Cottonseed is a monsoon season or kharif crop. As the monsoon advanced, the andolan or satyagraha, as the farmers’ union call it, picked up pace. About two dozen farmers planted HTBT cotton and made a public show of it.

On June 24, Laxmikant Kauthakar of Adgaon Buzurg village in Maharashtra’s Akola district and 10 others, including Bahale, were booked under the Seed Act, the Environment Protection Act and Sections 143 (unlawful assembly), 180 (refusal to sign statement), 188 (disobedience of public servant’s order) and 420 (cheating) of the Indian Penal Code.

Akola District Collector Jitendra Papalkar said the government had no issues with HTBT cotton, if it is approved. However, the seeds sown were not labeled. A sample was sent for testing to the Central Institute of Cotton Research, Nagpur. Papalkar wonders what will happen to the farmers if something goes wrong. “Who will take responsibility for the losses?” he asked.

On August 5, the Nagpur bench of the Bombay High Court restrained the State from taking criminal action against the farmers, said Anil Ghanvat, president, Shetkari Sanghatana.

Farmers say they are forced to break the law because approval for GM crops is stalled for political, and not scientific, reasons. Communist parties and farmers’ unions affiliated to them are opposed to multinational corporations (MNCs) and are reflexively anti-American. The biggest players in agricultural biotechnology are MNCs, led by the American company Monsanto (which has now merged with the German Bayer).

Within the Sangh Parivar family, the Swadeshi Jagran Manch is an implacable opponent of GM technology because it thinks it will put Indian agriculture in the thrall of Western companies. It believes farmers can practice traditional agriculture profitably and sustainably. The ruling party’s thrust is on organic farming. GM technology does not qualify as organic though some ecologists like Ullas Karanth say it should because the bollworm- or borer-killing Bt technology obviates the need for pesticide sprays.

Even among the centrist parties, opposition to GM technology is pretty strong. Bihar Chief Minister Nitish Kumar has said GM mustard will not be allowed in the state. Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam’s MK Stalin has also opposed it even though mustard is not grown in Tamil Nadu. In a letter to former environment minister Harsh Vardhan (in the previous government), he had ignorantly claimed that the state does not grow any GM crops, though Bt cotton is grown in Tamil Nadu and the Coimbatore-based Rasi Seeds has a big business in Bt cottonseed.

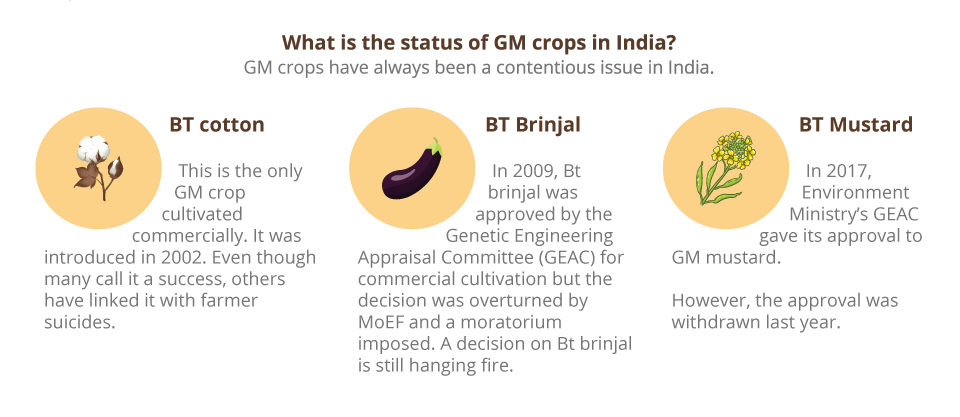

Piracy forces GM into India

It was the BJP-led government of Atal Bihari Vajpayee that approved India’s first and so far only GM crop — Bt cotton — for cultivation in 2002. It was compelled to as farmers in Gujarat had planted pirated Bt cottonseeds in 2001. The regulator — Genetic Engineering Approval Committee (GEAC) — ordered the crop to be burnt down, but the Shetkari Sanghatana, led by Joshi, mobilised farmers against the move. The government backed down. Narendra Modi was Gujarat’s chief minister at that time. The state’s agriculture minister was Parshottam Rupala, who is currently minister of state for agriculture at the Centre.

In the Congress party, former prime minister Manmohan Singh was in favour of GM technology. But his environment minister Jairam Ramesh vetoed the release of Bt brinjal in February 2010, even though the GEAC approved it. Ramesh also imposed an indefinite ban on its cultivation. The buzz was that Sonia Gandhi, the chairperson of the United Progressive Alliance, was influenced by her Left-oriented National Advisory Council. The ban could have been overturned by the Modi government but it has not so far.

Farmers want HTBT cottonseed because it saves the cost of weeding. According to a survey done by the National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO), wages are the single biggest item of agricultural cost. There is a perception in urban areas that rural labour is plentiful. It is not. The demand for agricultural labour is often concentrated to the time of sowing and harvesting. Even at higher wages workers are scarce at these times. Manual weeding in the black cotton soil areas of Maharashtra is difficult because the fields become slippery after the rain. Weeds, if not checked, will eat plant nutrients, resulting in poor harvests.

Although unapproved, there is a sizeable area under HTBT cotton. After analysing over 13,000 leaf cuttings, the Field Inspection and Scientific Evaluation Committee (FISEC) estimated that 15 per cent of the cotton area of Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana and Gujarat and 5 per cent of Punjab was planted with illegal HTBT cotton in 2017.

A member of the committee said they had found 20 hybrids with the HTBT trait. One set had been bred for Andhra and Telangana and another set for Maharashtra. The committee screened for seven HT genes that are in use worldwide and found the samples to contain technology from Mahyco Monsanto. He speculated that they were stolen and not leaked because the technology owners wouldn’t benefit from illegal sales. He said it was an organised effort that involved at least five years of breeding.

The way out

Environment minister Prakash Javadekar has said cotton with herbicide tolerance can be approved for cultivation, as the gene is stacked on to cotton with the bollworm-killing GM trait, which is already approved.

But there is no application for approval of HTBT cottonseed before the GEAC. In 2016 Maharashtra Hybrid Seeds Company or Mahyco (which licensed the technology from Monsanto) withdrew its application, afraid that it would not profit from franchising the technology even if it was approved. Radha Mohan, the former agriculture minister, had not only brought Bt cottonseed under price control nationally, he had also drastically reduced the fee payable by franchisees to the owners of patented GM traits. That had a chilling effect on agricultural biotechnology companies, including Dow Chemicals and DuPont. Unless the government gives an assurance that it will not interfere in pricing and royalty issues, it is unlikely that companies with proprietary GM technology will want to make them available in India.

In the case of Bt brinjal, Mahyco has asked GEAC to revisit the ban in the light of the Bangladesh experience. About 27,000 farmers are growing it there, up from 20 three years ago. Mahyco provided the technology free to the Bangladesh Agricultural Research Institute, which got approval for Bt brinjal on the basis of Indian bio-safety data. GEAC had asked the Indian Institute of Horticultural Research, Bengaluru, last year to present a report on Bangladesh’s post-release experience but when contacted its director said, it did not have the wherewithal to do a study in another country.

Two farmers who planted Bt brinjal in Haryana had their crops destroyed by the government earlier this year. Those farmers said even though they paid a higher price for the seedlings they were more than compensated by the saving in pesticide costs. Brinjal is one of those vegetables that is virtually doused with pesticides because the fruit and shoot borer is hard to reach once it lodges itself inside the fruit.

In May 2017 GEAC recommended to the government that GM mustard was safe and should be approved for cultivation. The GM mustard hybrid, DMH-11, was developed by a team of Delhi University (DU) scientists, led by its former vice-chancellor Deepak Pental, with public funds. The GM technology that it has employed allows hybrids in mustard, which is a self-pollinating crop, to be efficiently made. Anti-GM activists have doubted the yield claims made for DMH-11. Even if they are right, the DU technology can be used to cross superior parents for more productive hybrids.

Pental’s work is an entirely swadeshi effort. But the Swadeshi Jagran Manch has opposed its release, saying it is tolerant to a herbicide developed by Bayer and the DU team is fronting for the MNC. The Prime Minister’s Office is said to be in favour of its cultivation. When Prakash Javadekar was environment minister in the previous government, he had told this correspondent he was “determined” to approve GM mustard. Before he could do so, he was given the HRD portfolio.

The president of the Shetkari Sanghatana, Ghanvat, who practices farming in Ahmednagar, says, “This government has forced us to become smugglers.” The risk is that the farmers are not assured of quality seeds despite paying a hefty price to the pirates. If seeds with doubtful herbicide-tolerance or insect-resistance potency are sown, weeds and insects will develop resistance over time.