- Home

- News

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- World Cup 2023

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Premium

- Science

- Brand studio

- Home

- NewsNews

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Sports

- Loading...

Sports - Features

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium

For waterman, Ganga is so holy yet so unholy

During elections, river pollution is not a serious issue for Indian politicians, especially when there are bigger problems to milk such as joblessness and farmer distress. But for Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who began his 2014 campaign with “Mujhe toh Ma Ganga ne bulaya hai (Mother Ganga has called me),” the very same river may prove to be his undoing, according to Rajendra Singh,...

During elections, river pollution is not a serious issue for Indian politicians, especially when there are bigger problems to milk such as joblessness and farmer distress. But for Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who began his 2014 campaign with “Mujhe toh Ma Ganga ne bulaya hai (Mother Ganga has called me),” the very same river may prove to be his undoing, according to Rajendra Singh, Ramon Magsaysay Award winner and India’s water warrior. “The people of Varanasi remember and feel betrayed by him,” he told this writer.

- Ganga river basin fact sheet:

- Length of Ganga: 2525 km

- The main branch of the Ganga passes through five states — Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand and West Bengal, where it travels through 66 districts, 118 towns and 1,657 gram panchayats.

- The Ganga basin is the largest river basin in India in terms of catchment area. Spread over 26% of the country’s land mass, it covers 8,61,404 sq km.

- (Source: https://nmcg.nic.in/location.aspx)

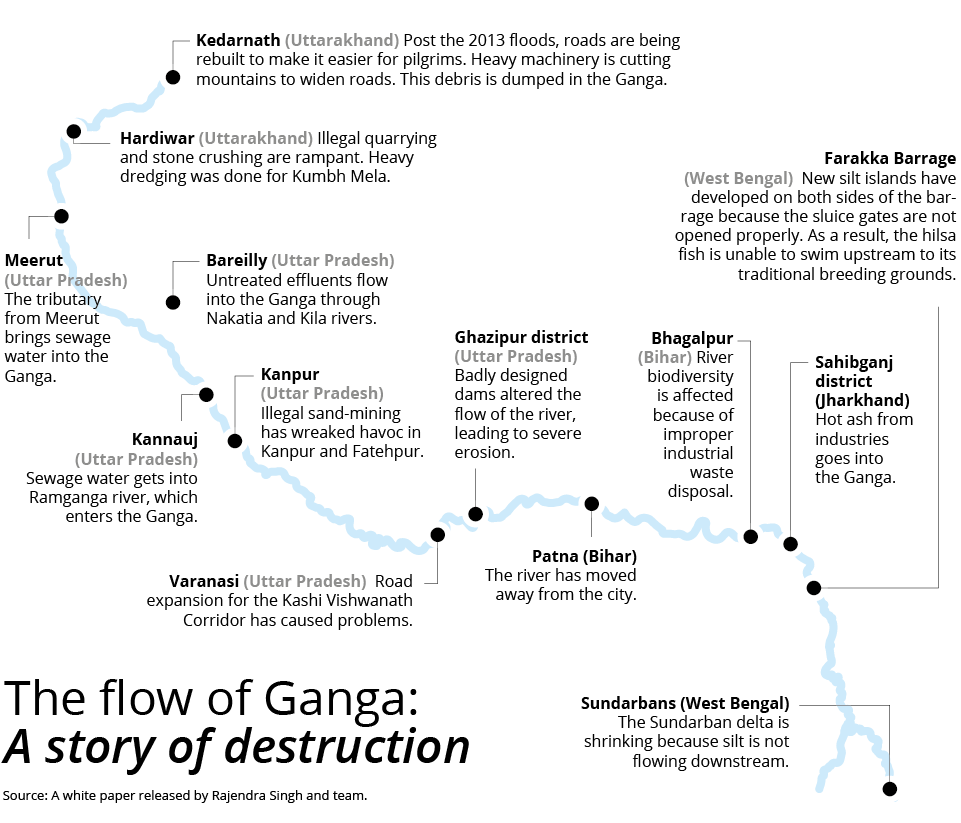

Over the years, various bodies have been set up by different governments to clean the Ganga but none have succeeded. The river’s condition is only getting worse. Singh and his team undertook a 111-day expedition tracking the river from its source at Gaumukh to its destination at Ganga Sagar to assess the situation on the ground and see if any of the assurances of cleaning the Ganga were fulfilled. Instead they found a trail of broken promises. Superficial beautification aside, very little has been done to reduce pollution levels in the river and restore its health, they found. After the 2,500-km Ganga Sadbhavana Yatra, Dr Singh released a white paper documenting the river’s health on January 12.

According to the report, in the upper regions of the Himalayas, where the river is supposed to be pristine and pure, there is large-scale road construction work taking place. After the 2013 floods, which affected holy sites like Kedarnath and Badrinath, roads are being rebuilt for pilgrims. Badrinath sees a heavy flow of visitors from April to October as part of the Char Dham Yatra. Heavy machinery is deployed to cut the mountains and widen the roads. This is not only destroying the fragile Himalayan ecosystem, but the mountain debris is dumped in the Ganga. This causes a disturbance in the river and the water level to rise.

As you come down from the mountains, to Haridwar, more than 100 stone crushing operators work day and night on the riverbed. Illegal quarrying and stone crushing activities are rampant but little preventive action is taken as the nexus allegedly includes administrative officials, claim various NGOs and groups. In addition, the white paper says that 96% of the river’s water is sent into the Upper Ganga Canal and only 4% flows down the mainstream river.

Ganga, viewed as holy and personified as ‘Ma’, sees a continuous influx of devotees throughout the year. In preparation of the Kumbh Mela, heavy dredging was done to make temporary bridges on the river to help pilgrims. Just outside Haridwar, at Jagjeetpur, the town’s sewage goes straight into the river, turning it into a dirty stream.

As you go further down, preparation for a yatra at Alwara in Uttar Pradesh is testimony to the fact that no one is bothered about the Ganga’s health, the report says. Old river rejuvenation structures, like johads (traditional, community-owned rainwater storages) and check-dams, have been destroyed and this has made the river water-starved in many places.

Sewage treatment plants, present along the banks of the river, are more like show pieces. Most of them don’t function, found Dr Singh and his team. At Bareilly, Uttar Pradesh, untreated effluents are discharged into the Ganga through the Nakatia and Kila rivers. Rivers Hindon and Koshi, which flow through Meerut and Rampur, bring sewage from these places to the Ganga.

Another problem in Uttar Pradesh is badly designed dams that have altered the flow of the river, leading to severe erosion in Saidpur, Dharampur, Tarighat, Puraina, Yuvrajpur, and surrounding villages. As a result, settlements are uprooted and people fight over land. Wastewater enters the Ramganga river, a tributary of the Ganga, in Kannauj. In Kanpur and Fatehpur, illegal sand-mining has wreaked havoc on the river.

In Varanasi, where Modi is contesting this Lok Sabha election, nearly 300 small, old temples were razed in the name of development, much to the ire of residents. The PM’s pet project, the Kashi Vishwanath Corridor, plans to expand the road to make it easier for devotees visiting the Kashi Vishwanath temple. The pathway will begin from the Lalita ghat, on the banks of the Ganga, and head towards the Vishwanath temple.

The ₹20,000 crore budgetary allocation for Namami Gange has been used to build and beautify ghats, but not revive the Ganga.

In Bihar’s capital, Patna, the river has moved away from the city. The Ganga has already shifted 2.5-3.5 km from most ghats, according to reports. Yet, nothing much is being done about it. The river’s biodiversity is severely affected further down in Bhagalpur, where the fishing industry has taken a hit. In Jharkhand’s Sahibganj district, hot ash from industries goes straight into the river, adding to the pollutants.

As one heads into West Bengal, erosion at Farakka Barrage is reducing the landmass of India and increasing that of Bangladesh. New silt islands have developed on both sides of the barrage because the sluice gates are not opened properly. Fishermen observed that the hilsa fish is unable to swim upstream to its traditional breeding ground due to this. However, grand schemes like Namami Gange divert the attention of people from these issues.

Rajendra Singh, also known as the ‘Waterman of India,’ is a water conservationist and environmentalist from Alwar district in Rajasthan. Singh is known for his catalysing role in the building of 8,600 johads, or community-owned traditional water harnessing resources, in 1,058 villages of Rajasthan. He won the Magsaysay Award in 2001 and was named the 2015 Stockholm Water Prize Laureate for his innovative water restoration efforts. Singh is the founder of an NGO called Tarun Bharat Sangh, which aims to empower rural communities.

Rajendra Singh, also known as the ‘Waterman of India,’ is a water conservationist and environmentalist from Alwar district in Rajasthan. Singh is known for his catalysing role in the building of 8,600 johads, or community-owned traditional water harnessing resources, in 1,058 villages of Rajasthan. He won the Magsaysay Award in 2001 and was named the 2015 Stockholm Water Prize Laureate for his innovative water restoration efforts. Singh is the founder of an NGO called Tarun Bharat Sangh, which aims to empower rural communities.

Dr Singh’s report also addresses the issue of flooding that happens in the delta region. “The problem of flooding is because insufficient water is released during the lean period,” says Singh. At least 60% of the water must be given to the mainstream during this period and the greenbelt coverage on riverbanks must be conserved. Dredging is not the solution for silt sedimentation, he says. When the river is in full flow all year round, then the silt automatically gets carried to the Sundarbans and helps in delta formation. Currently, the Sundarban delta is shrinking because the silt does not flow downstream.

Many environmentalists have protested the exploitation and slow killing of the Ganga. But most of them are labelled anti-national and silenced through indifference or threats. Singh, however, is undaunted by the trail of unkept promises. His team is currently on a pan-India Ganga Aviralta Yatra to increase awareness about the need for a free-flowing river. “The nations need a Ganga revolution, now,” he concludes.