- Home

- News

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- World Cup 2023

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Premium

- Science

- Brand studio

- Home

- NewsNews

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Sports

- Loading...

Sports - Features

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium

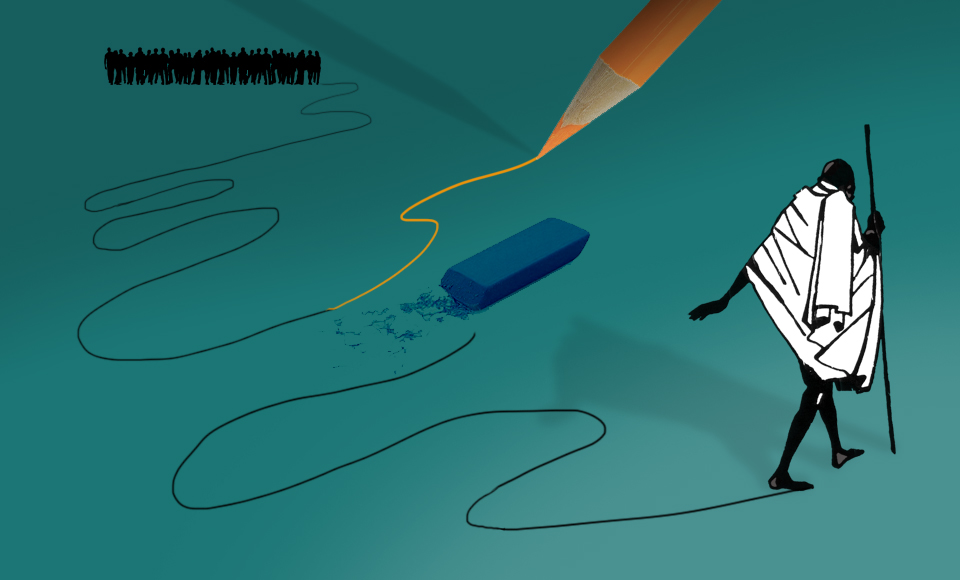

Freedom and integration: A swaraj of the Mahatma's dream

Security measures beefed up across the country ahead of the 73rd Independence Day celebrations, read some of the headlines. But does every part of the country celebrate freedom in equal measure? Many would like to avoid answering that question since such deliberations may invite action under a more stringent Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, which can declare an individual a...

Security measures beefed up across the country ahead of the 73rd Independence Day celebrations, read some of the headlines. But does every part of the country celebrate freedom in equal measure?

Many would like to avoid answering that question since such deliberations may invite action under a more stringent Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, which can declare an individual a terrorist.

What would Mahatma Gandhi have thought about the current situation?

We can only speculate.

“Let no one be forced into anything. Let there be no coercion,” he said at a prayer meeting in New Delhi on October 26, 1947, according to The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi.

Speaking about the princely states and their accession to India, Gandhi said: “I must respectfully submit that today Kashmir is not ruled by its Maharaja. In other states too there are no princes as we used to know them. They were the creation of the British. Now the British have gone. They had installed them as rulers because they could rule through them and exercise power. Kashmir has still to establish popular rule in the state. The same is the case with other states like Hyderabad and Junagadh. In my view there is no difference between them.”

Gandhi clearly advocated giving people the freedom to choose their own destiny.

“Real rulers of the states are its people. If the people of Kashmir are in favour of opting for Pakistan, no power on earth can stop them from doing so. But they should be left free to decide for themselves. The people cannot be attacked and forced by burning their villages. If the people of Kashmir, in spite of its Muslim majority, wish to accede to India no one can stop them.”

The Mahatma had the same advice for both India and Pakistan.

“The Pakistan government should stop its people if they are going there to force the people of Kashmir. If it fails to do that, it will have to shoulder the entire blame. If the people of the Indian Union are going there to force the Kashmiris, they should be stopped, too, and they should stop by themselves. About this I have no doubt at all.”

Gandhi had been profoundly disturbed that the once creative and vibrant Hindu civilisation had become degenerate, diseased and feeble, and as a consequence fallen prey to waves after waves of foreign invasions. He reflected deeply on the nature and causes of its degeneration and concluded that unless radically revitalised and reconstituted on the foundation of a new yugadharma, it was doomed.

He began to search for and establish dharma appropriate to India in the modern age. He tried making sevadharma the essence of Hindu dharma. He knew how to tap and mobilise the regenerative resources of the tradition but then he held a unique moral and political authority. He critiqued unacceptable beliefs and practices. Sometimes he won. Many a time defeated.

Gandhi looked at tradition as a resource stressing the role of reason as having no hostility with it. For him, tradition was not a mechanical accumulation of precedents but a product of countless conscious and semi-conscious experiments by rational men over several generations. Reason, he felt, lay at the heart of tradition manifesting itself in abiding values and organising principles

Gandhi wanted universal decentralisation and moral constraints to be the goals of a political system. Of course, no politician would agree with him. Power lies in control and decentralisation is the loss of that power.

For Gandhi, progress or development was not an exclusive linear movement but an inclusive holistic process. His sarvodaya — the ennoblement of all, for every human being to be able to blossom first within limitations and then within their own space, time and society, and then to flower out in fulfilling self-expression constantly in consonance with fellow humans.

This is what he said about Jammu and Kashmir in another talk on November 11, 1947 in New Delhi: “Whatever I have said about Junagadh equally applies to Kashmir and Hyderabad. Neither the Maharaja of Kashmir nor the Nizam of Hyderabad has any authority to accede to either Union without the consent of his people.”

“As far as I know, this point was clarified in the case of Kashmir. If it had been only the Maharaja who had wanted to accede to the Indian Union, I could never support such an act. The Union government agreed to the accession for the time being because both the Maharaja and Sheikh Abdullah, who is the representative of the people of Jammu and Kashmir, wanted it. Sheikh Abdullah came forward because he claims to represent not only the Muslims but the entire masses in Kashmir.”

The Mahatma expected Indians to be sensible.

“I have heard people talking in whispers that Kashmir could be divided. Jammu would come to the Hindus and the Muslims would have Kashmir. I cannot even think of such divided loyalty and division of the Indian states into several parts. Hence, I hope that the whole of India would act sensibly and this ugly situation would be avoided soon at least for the sake of lakhs of Indians who have been compelled to become helpless refugees.”

“The Nawab of Junagadh after consenting to accede to India, had revoked his decision, fled to Pakistan and executed an Instrument of Accession on September 15, whereby the state was declared to have acceded to Pakistan. The government of India refused to accept the accession of Junagadh to Pakistan in the circumstances in which it was made,” said Gandhi.

The Nizam wanted “Hyderabad to be an independent sovereign state” and refused to accede to the dominion of India. After prolonged discussions between the government of India and the Nizam, a delegation led by the Nawab of Chhatari arrived at a draft standstill agreement on October 22. The Nizam, however, against the advice of his Council, dissolved the delegation and appointed a new one on October 29 (Vide ‘Fragment of A Letter’, 26/11/1947).

The government of India, while accepting the accession of Jammu and Kashmir to India, had “made it clear to the Maharaja that, as soon as the invaders have been driven from the soil of Kashmir, the people of the state should decide the question of accession”.

Gandhi rejected violence on moral grounds. He argued that violence could never achieve lasting results. Every successful use of it blunted the community’s moral sensibility.

In Gandhi’s view, building up the pride and self-confidence of a diffident and long-oppressed people, atmasuddhi (soul-cleansing) as he called it, was an immensely complex and protracted task calling for great patience, hard work and skillful organisation. It required living in the remotest villages, educating illiterate people, organising them, teaching them sanitation, hygiene and habits of cooperation, building up their economic strength, reconciling those long divided by deep cultural, religious, linguistic and other differences and healing wounds.

The pilgrimage to ‘swaraj’, he said, is a painful climb and not like a “a magician’s mango that could spring up from nowhere merely by engaging in heroic deeds”.

(VR Devika is a scholar in Gandhian studies and a social entrepreneur. She is the founder of Aseema Trust.)