- Home

- News

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- World Cup 2023

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Premium

- Science

- Brand studio

- Home

- NewsNews

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Sports

- Loading...

Sports - Features

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium

Bengaluru makes an attempt to explain letters used in its Singapura

There are many Singapuras in India as well as abroad. But how many of us know that there was a Singapura in Bengaluru, 17 km from today’s Majestic and three km from the Yelahanka bus stand. The earliest map of Singapura dating back to 1915 CE shows the village had two lakes, one pond, eight wells, three water holes and five hillocks. The revenue village had a perimeter of seven km and an...

There are many Singapuras in India as well as abroad. But how many of us know that there was a Singapura in Bengaluru, 17 km from today’s Majestic and three km from the Yelahanka bus stand. The earliest map of Singapura dating back to 1915 CE shows the village had two lakes, one pond, eight wells, three water holes and five hillocks. The revenue village had a perimeter of seven km and an area of 3.3 sq km (815 acres). The population data from the first Mysore state Census in 1871 CE shows Singapura had 34 homes with 60 men and 73 women. But the same area is home to more than 40,000 people today.

Like many metros, urbanisation in the name of development in Bengaluru has led to destruction of many of its inscription stones, one of the main sources of history of a place and its people. However, since the launch of ‘Inscription Stones of Bangalore’, a citizen activism project to raise awareness among people and protect ancient inscription stones in 2017, things have changed. The team, led by PL Udaya Kumar, with the support of the Mythic Society, has preserved more than 200 inscription stones in Bengaluru and its surrounding areas so far.

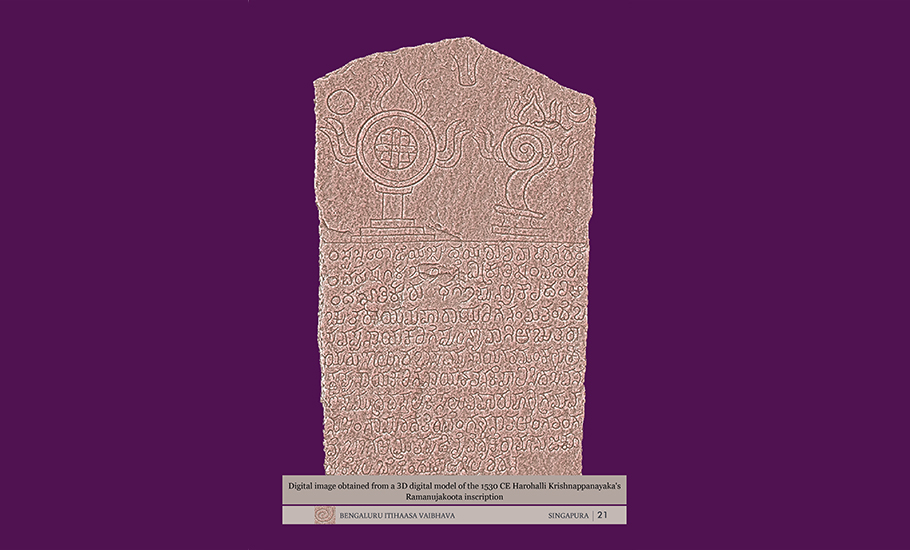

The story, however, doesn’t end with preservation. The Mythic Society Inscriptions 3D Digital Conservation Project uses advanced technologies such as mapping, 3D scanning and optical character recognition to restore those inscription stones. The team, supported by a panel of epigraphists, then studies the highly accurate 3D digital model of an inscription developed from digital 3D scans and deciphers the text of the inscription. The team conducts awareness lectures based on their findings.

A couple of months ago, the team released a bilingual magazine, Bengaluru Itihaasa Vaibhava, detailing the history of localities and villages in Bengaluru Urban, Bengaluru Rural and Ramanagara districts (the earlier undivided Bengaluru district). “Our fact-based history narration drives from information recorded in stone inscriptions we have intensely studied using modern technological methods and processes. This first issue of the magazine was about Singapura, a historical locality in north Bengaluru,” says Udaya Kumar.

“We believe it is a serious shortcoming that local history is not known to residents. Therefore this magazine is written for ordinary and local citizens. These readers could be children, students or adults. Therefore, the language and style we use in the magazine are such that even a curious child can read and learn from it the story of its neighbourhood,” he says. “Our aim for the magazine is that it be read and understood by scholars and ordinary people of all backgrounds. It is freely shared electronically via social media platforms,” he adds.

While there are a number of academic documents available on the historic and prehistoric periods, there is a lack of such documents when it comes to local and subaltern history of the region. Stone inscriptions are considered a significant source of information when it comes to history. Still, inscriptions and their decipherments are limited to scholars.

“The laymen in Bengaluru are not aware of the exact information contained in an inscription or its historical importance. We address this problem by helping conserve inscription stones physically and digitally by using cutting-edge technologies such as high-resolution 3D digital scanning. The team aims to digitally conserve some 1,500 stone inscriptions found in Bengaluru Urban, Bengaluru Rural and Ramanagara districts,” he says. About 70-80 per cent of the 1,500 inscriptions in the three districts were first documented in the Epigraphia Carnatica Vol. 9, 1905 CE edition, published by Benjamin Lewis Rice, the father of Karnataka Epigraphy.

Udaya Kumar said this modern technique is a huge improvement over traditional 2D methods such as estampage or flour tracing for reading inscriptions; its most important benefit is that once an inscription stone is scanned it is accurately preserved for posterity. “A 3D digital model also provides the ability to recreate exact physical copies of the inscription stone in metal, wood, stone…in whatever material of whatever sizes we want,” he says. K Dinesh, a resident of Bengaluru, said the magazine was an eye-opener for him.

“I have been living in Bengaluru for three decades but I never knew the history of the place until I read the magazine. I have learnt how to read inscriptions thanks to the magazine. I am waiting for the next issue,” he says.

Every inscription, according to Udaya Kumar, is a direct written message from people in the past telling us about something interesting and important that happened at that location.

“Even though most inscriptions are in Kannada, we also found many inscriptions in Tamil, Telugu and Sanskrit,” he says. The lockdown, however, gave enough time for the team to sit and work. “We used to conduct many awareness lectures in schools and other public places. When lockdown restricted our movements, we got enough time to sit and bring out a magazine like this,” says Udaya Kumar. The Mythic Society Inscriptions 3D Digital Conservation Team comprises five people—MG Byrappa, MN Madhusudhana, KC Shashi Kumara Naik, PL Udaya Kumar and R Yuvaraju. Founded in 1909 CE, the Mythic Society is a pioneer institution in the area of Indic studies.

This first issue of Bengaluru Itihaasa Vaibhava has focused on the factual history of Singapura, its people, their beliefs and their practices. The team has used three inscriptions (the newly discovered Singapura Nalapanayaka’s inscription (1528 CE), Harohalli Krishnappanayaka’s Ramanujakoota inscription (1530 CE) and Chikkabettahalli Singappanayaka’s Ramanujakoota inscription (1524 CE), the 500-year-old Varadaraja Swamy temple at Singapura, a prehistoric site (the Jalahalli microlithic tools factory), Roman coins discovered at Yeshawantapura to unravel the history of Singapura.

Rajendra Shetty, a teacher, said the bilingual edition of the magazine will help reach more people. “The magazine has taught me how to approach history in a simple way. Since the magazine appears in both Kannada and English, it will reach more people,” he says.

The name Singapura may have its roots in the Kannada word ‘singa’ and ‘pura’. Singa is an equivalent term for ‘simha’, which means lion. The word ‘pura’ has many meanings. It has been used for forts, a donated village, a secure place or a place smaller than a city. Adjoining Singapura is the massive 1600 acre Air Force Station Jalahalli.

“Much of this land belonged to the 1915 CE Singapura revenue village. The Jalahalli station is one of India’s largest Indian Air Force (IAF) training centres with some 60-70 per cent of its personnel getting trained here every year. Before being an Indian Air Force training centre, it was a Prisoner of War (POW) camp during the Second World War (1941-45). About 22,000 Italian POWs captured in Africa were housed in the Singapura, Jalahalli, Hebbal, and Jakkur regions,” says the research team of “Bengaluru Itihaasa Vaibhava.”

The magazine (https://bit.ly/Bengaluru_Itihaasa_Vaibhava_Singapura_English) will appear in English as well as in Kannada. The Kannada version of the second edition of Bengaluru Itihaasa Vaibhava has been released. The English version, however, will be released at the end of February or March. “We will highlight similar other histories of Bengaluru’s localities and villages in the coming issues of the magazine,” says Udaya Kumar.