- Home

- News

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- World Cup 2023

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Premium

- Science

- Brand studio

- Home

- NewsNews

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Sports

- Loading...

Sports - Features

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium

Ambedkar: The man from Manhattan

Ambedkar, whose 128th birth centenary was observed on Sunday, April 14, has become the elephant in a game of blind men and the elephant. Hindutvavadis see in his virulent criticism of Islam and the role of Muslims in Indian history a vindication of their own political agenda. Dalit intellectuals and politicians see in his political activity and intervention in favour of social justice as the...

Ambedkar, whose 128th birth centenary was observed on Sunday, April 14, has become the elephant in a game of blind men and the elephant. Hindutvavadis see in his virulent criticism of Islam and the role of Muslims in Indian history a vindication of their own political agenda. Dalit intellectuals and politicians see in his political activity and intervention in favour of social justice as the most significant, overarching aspect of Ambedkar relevant today. Leftists cite his advocacy of a form of socialism. With the BJP having struck a growth path, Leftists have recently taken up the task of rediscovering Ambedkar and linking Ambedkarism with their own beliefs to build a broader alliance against the BJP.

While all these dimensions that people discover in Ambedkar are consequences of Ambedkar’s fundamental worldviews they are not the worldviews themselves. They are inferences Ambedkar drew based upon his core beliefs. Those beliefs, largely coming from western liberalism, can however form the template of liberal democracy that can define the political agenda of India in the future.

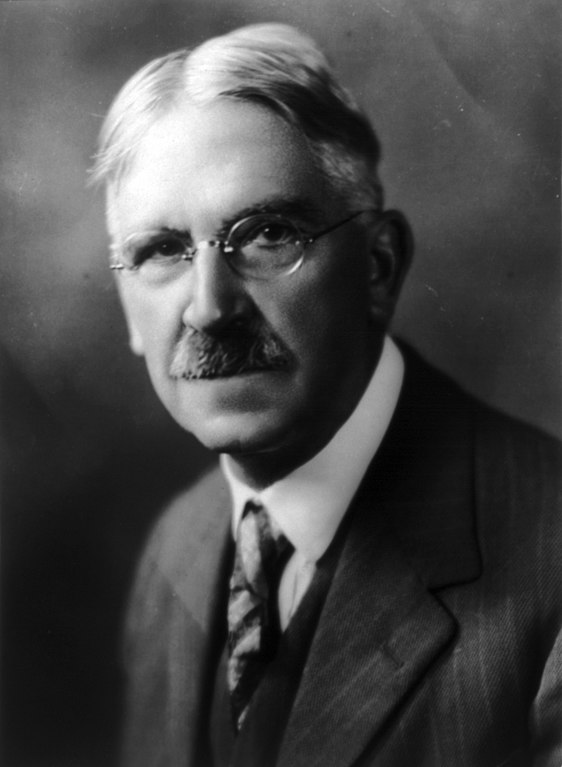

His Guru was an American academic

To think about Ambedkar, one will have to go back to an American academic named John Dewey, a professor at Columbia University where Ambedkar studied. Ambedkar openly called Dewey his master, his intellectual father figure. When Ambedkar was feted at Columbia University in the 1950s, what he looked forward to most was meeting Dewey but sadly Dewey had passed away when Ambedkar was on his way to America.

Dewey was already on the road to becoming a legend when Ambedkar landed at Columbia as a student in 1913. It is not hard to imagine what impression a kindly, unassuming and caring professor at an American university had on an Indian who had faced much discrimination, doubt and negativity over his potential back home. For all its shortcomings, American academia marked by high standards of education and quality research was and is one of the highpoints of the US. For a dalit student from India in the second decade of the 20th century, Manhattan in New York must have opened hundreds of intellectual doors closed to him in India.

Dewey’s philosophy, called loosely as pragmatism, did not lay down a rigid system but emphasized practicality and utility, besides scientific rigour and action. Importantly for Ambedkar, the philosophy had little value for the past save what was relevant for the present. Unlike an Indian who would inevitably valorize the past, Dewey valorized the individual in his present circumstances and constantly looked for tools that could help to achieve his or her growth.

Dewey was steadfast in his advocacy of individual freedom though not anarchy. He was one of the founders of the American Civil Liberties Union that in the past defended even the racist Ku Klux Klan’s right to hold meetings.

John Dewey was an anti-communist constitutionalist. He helped to initiate coordination between big business, government and labour unions to implement Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal that pulled America out of Depression. But he later veered to the left of Roosevelt and advocated socialism, which, for him, meant not state ownership of industry but a society directed by what he called organized intelligence. Dewey found such an intelligence in the process of science in which an individual is free to pursue his ideas and career even if it was in conflict with the norm but his work had to be recognized and taken forward by peer review and acceptance.

A reformed and reconstituted education system was necessary for the growth of the individual and society. Dewey’s theories on education have been widely implemented in the US. In them, education involved directed activity, experimenting and personal inquiry as opposed to learning of skills and techniques. Dewey saw schools and colleges as only a part of the education system and recommended breaking barriers between the school and society. Ambedkar’s politics gave much importance to education as an instrument of personal and social growth although it is quite possible that he wouldn’t have accepted opening up schools to the community since in India the community was typically caste-based.

Having studied in the West, Ambedkar sought a bright shining light of liberalism in India — a man who would stand for personal freedom, individual advancement, a searingly critical attitude toward the past, and illuminating a way forward. He didn’t find one.

In Gandhi, he saw one of the worst apologists of the caste system. Nehru, for all his modernism and distrust of a past that promoted social injustice, was at the same time awed by the civilizational baggage of India.

Ambedkar savaged Indian religions like a Deweyite would. He did not see Hindus as coming close to the Deweyan standard of a community. And, in any case, Hindus and Muslims had little like-mindedness, to use a Deweyan term for the requirement of a community to form. For Ambedkar, the lack of any like-mindedness promoted by hundreds of years of conflict and hostility gave the logic to partition. And he supported the formation of Pakistan.

Ambedkar said brahmins were learned people but they couldn’t produce a Voltaire for a Voltaire would have to critique the past in a wholesome fashion. Ambedkar’s critique of the caste system was based on the values of liberalism. He sought to free the individual in India from structures that stifled freedom, not to promote an alternate communitarian identity.

His critical attitude to Islam and Muslims centred around Muslim politics that was caught in the pre-colonial narrative of having ruled India for centuries. Like a true Deweyite, he did not dwell much on theological questions. Cosmological, ultimate and essential topics had no use for him.

Sanghis sometimes cite his occasional laudatory references to the Upanishads although elsewhere he has critiqued the same Upanishads for not measuring up to Buddhist thought. Even in the praise he had for the Upanishads, Ambedkar was seeing if the Upanishads had any use in the present in terms of influencing one’s attitude to democracy. And he found that, conceptually, the Upanishads could support democracy.

Ambedkar was a scholar who brought a critical eye to the topic on hand. His was a commitment to unflinching truth-telling. He was a scholar first, a politician next. He was not interested in constructing a grand political philosophy or system. His books did not serve any politically tactical purpose. They were meant to lay bare the subjects and answer key questions. For instance, he wrote that the shudra was downgraded in the caste hierarchy because he had challenged brahmins. He also said that the “broken men”, those outside the caste system who are today called dalits, were outsiders to the brahminical system because they were beef-eaters, and were likely the historical Buddhists who had lost to brahmins. For that reason, they were characterized as untouchables so that the brahminical system could be kept in place.

Ambedkar decided to leave Hinduism because he concluded that was the only way to escape the caste system. He has written against converting to Islam and derided Christian missionary activity among untouchables.

Dalit leaders in Tamil Nadu, too, had earlier advocated converting to Buddhism, many years before Ambedkar, seeing it as the religion of their forefathers. But Ambedkar was likely not motivated by a desire to return to the past or the origins. He saw Buddhism as a Manhattan liberal would and still does – Dalai Lama’s meetings are typically full-house in New York City.

The Buddha ignored ultimate cosmological questions. He was agnostic, had little use for the past, and laid down a practical path for individual growth. Master Dewey would have appreciated Ambedkar’s choice.

Ambedkar was interested in scholarship and wanted to be engaged in the great battles for justice and equality in society – again a Deweyite trait. For that reason, he often went beyond his primary expertise, which lay in economics.

His work in economics, too, was grounded in American liberalism. Theorizing on how to create a pan-Indian currency system, he advocated full convertibility of the Indian rupee and retaining the gold standard – all anathema to Soviet-style socialistic planning that was fashionable during his time. He advocated mixed economy and communitarian farming that would allow the market do its job. Like a true liberal for whom the individual was primary, Ambedkar distrusted Marxism.

Why India needs a Voltaire

As the BJP gains ground in India and pushes for an increasingly right-wing agenda in politics and society, it would serve India if a political pole is built around a more thorough-going liberalism than India has seen. That liberalism would include a commitment to individual rights, growth and freedom, while promoting the market to deliver on economic efficiency. A thoroughgoing liberalism would open a window for India. For that to happen, it may be time to make Ambedkar, the man from Manhattan, India’s Voltaire. Ambedkar came from the most underprivileged section of Indian society and was therefore eminently qualified to push for a liberal agenda.