- Home

- News

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- World Cup 2023

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Premium

- Science

- Brand studio

- Home

- NewsNews

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Sports

- Loading...

Sports - Features

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium

A sincere ‘sorry’ can replace courts to ensure justice

In a school in Bengaluru, every student from class one to 10 sits around in a circle for at least 40 minutes every week. The students have teachers sitting amid them, voicing their views and thoughts on any given topic. The talking points range from the idea of friendship to the students’ understanding of the concept of betrayal. But the discussion stays there, and the group vows neither...

In a school in Bengaluru, every student from class one to 10 sits around in a circle for at least 40 minutes every week. The students have teachers sitting amid them, voicing their views and thoughts on any given topic. The talking points range from the idea of friendship to the students’ understanding of the concept of betrayal. But the discussion stays there, and the group vows neither to gossip about it nor ridicule the thoughts or ideas shared by fellow students or teachers.

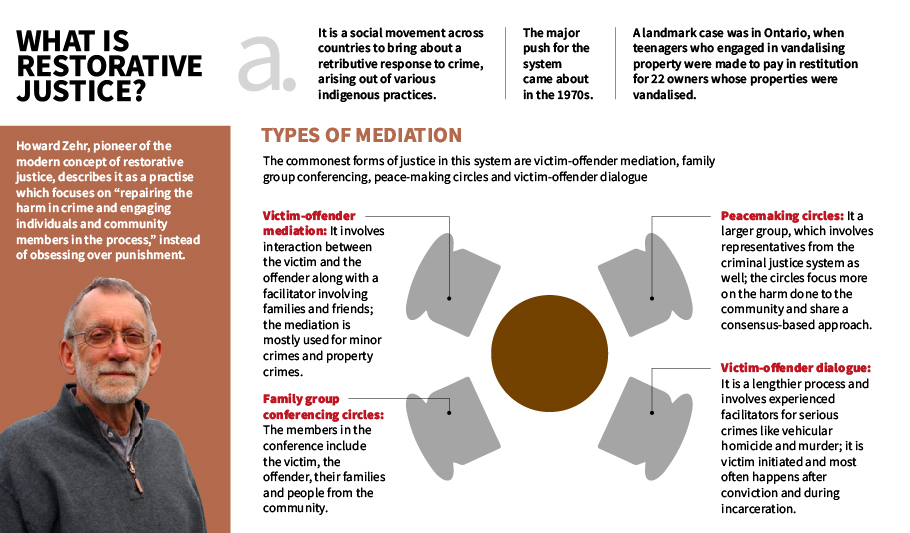

The exercise, where everyone is equal and the circle an equaliser, is an attempt to build relationships and a sense of community among students. Popularly known as restorative practice, it aims to create an environment, where the community enables an individual who might have harmed another, to admit to the mistake, create a dialogue to avoid its repetition in future and make amends to the situation.

The example of the school’s community is just a microcosm of how the concept could be implemented to address petty crimes and provide relief to victims through community intervention.

Talking it out

Arlene Manoharan, a consultant on restorative justice, rehabilitation and re-integration, describes how the practice can help in initiating a process called restorative justice, where the victim, the offender and the community are all made to have a dialogue to look at ways to meet the victim’s needs.

She says that restorative practice can work very well in the case of observation homes and child care institutions, as they have witnessed through their work.

Also read: Is playback theatre changing teacher-student relationship in Khammam?

“We first train the staff (of the institutions) in it before taking it up with the children or inmates. In one of these homes for girls who need protection and care in Bengaluru, one of the topics that came up for discussion in a circle was ‘recall a happy childhood memory’ and a staffer told us she didn’t have any before she began weeping. This was a revelation, as these are caregivers for children in need of care and protection. Towards the end of the session, she told us that this was the second time she was being heard. That is what being non-judgmental, caring and listening to their stories can do to a person,” she says.

Arlene, who is working with adolescent boys lodged in observation homes in Bengaluru as well, explains, “These boys are often angry young men and have been in conflict with law. The homes have to be a safe space for them to share their experiences and thoughts. Through the circles we have discussions with them about hopes and what they aim to be in their lives.”

Dr Sangeeta Saksena, co-founder, Proactive Health Trust says that restorative practices can be used to build relationships between people in any setting where all of them can learn from each other — community, corporates and even classrooms as seen in the above example. “There are people, who have such circles even in their family set up. Within our organisation too we hold such discussions when someone new joins us or when someone is leaving,” she adds.

A realisation, an apology to heal wounds

Shyam (name changed), who was in his teens, was part of a gang that vandalised a shop to settle scores with the owner. The case dragged on in court for almost two years. When one of the organisations, Counsel to Secure Justice (CSJ) in New Delhi working on a pilot project on restorative justice, stepped in by bringing the complainant and the offender face-to-face, the latter admitted he had been part of the gang which had destroyed the shop, at the behest of his uncle.

“The minute they came face-to-face and the complainant realised that the offender was a youngster, who was admitting to his mistake, he decided to forgive him and let go,” says Nimisha Srivastava, programme director, CSJ.

CSJ has been moderating such discussions related to minor offences, with the support of the Juvenile Justice Board. Nimisha says the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015 stresses more the principle of diversion or promoting “measures for dealing with children in conflict with law, without resorting to judicial proceedings”.

Organisations like Enfold Proactive Health Trust in Bengaluru, Ashiyana in Mumbai and CSJ in New Delhi have been carrying out restorative practices in various settings.

Also read: Do police stations frighten kids? The child-friendly ones in Thiruvallur don’t

Restorative justice, which is still in a nascent stage in the country stresses the offenders’ accountability apart from considering the needs of the victims. It also looks at empowering the victims and changing the behaviour of offenders. In countries like New Zealand, juvenile offenders come directly into the system of restorative justice, except in cases of manslaughter or murder.

Nimisha says that it is natural to link juvenile justice with restorative justice because both are co-related across the world.

“When tried in the criminal justice system, juveniles often graduate from smaller crimes to bigger crimes. And it doesn’t help them rehabilitate. A stint in the observation home often exposes them to violent children and addiction,” she adds.

Lack of rehabilitative measures in the criminal justice system, leaves very little scope for such children to change for the better, Arlene says. “There is much to be desired and it takes a lot to build a child who is remorseful and make them really apologise for the harm they caused. The system doesn’t allow it. You may give compensation to the victims, but their needs are not met and questions not answered,” she adds.

Not cut out for all cases

The process entails a lot of work involving both the victim (complainant) and the offender along with their family and members of their community. “Probably that is why it is seen as intensive, but it saves time and energy. It allows the community to step in rather than the state taking it up,” Nimisha says.

She also points out that this particular practice to provide justice is not recommended for all cases. “I wouldn’t say go for it to reduce the pendency of cases.”

And, the path is also fraught with challenges. “Schools often refuse to re-admit the child (offender) even after the due process is through. We are therefore working on a holistic model that addresses all these issues,” she adds.

Also read: Highest number of children in care homes, but TN cares little

In some cases, the child doesn’t have the expected congenial atmosphere at home to fall back on. “In such cases, we work with the family members or parents. There are issues of domestic violence in some homes and these also have to be dealt by us, as part of the process. It doesn’t end with just the victim-offender interactions,” adds Nimisha.

It is also a fallacy that the process of restorative justice is all about the offender apologising to the complainant, says Sangeeta. She adds, “It is about making them accountable and responsible for the actions and not about getting away lightly. The premise is saying, ‘I did it’, and about ‘what can I do to repair the harm’,” she says.

Experts on restorative justice say that with pilot projects being carried out in the country, it is still early days for the process to be established. Experts like Swagata Raha, a consultant on restorative justice and legal affairs, are at the moment looking at ways to work on cases in the entry point of the system.

“After the due process is completed, we can also look at ways in using it for integration of offenders,” she says.