- Home

- News

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- World Cup 2023

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Premium

- Science

- Brand studio

- Home

- NewsNews

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Sports

- Loading...

Sports - Features

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium

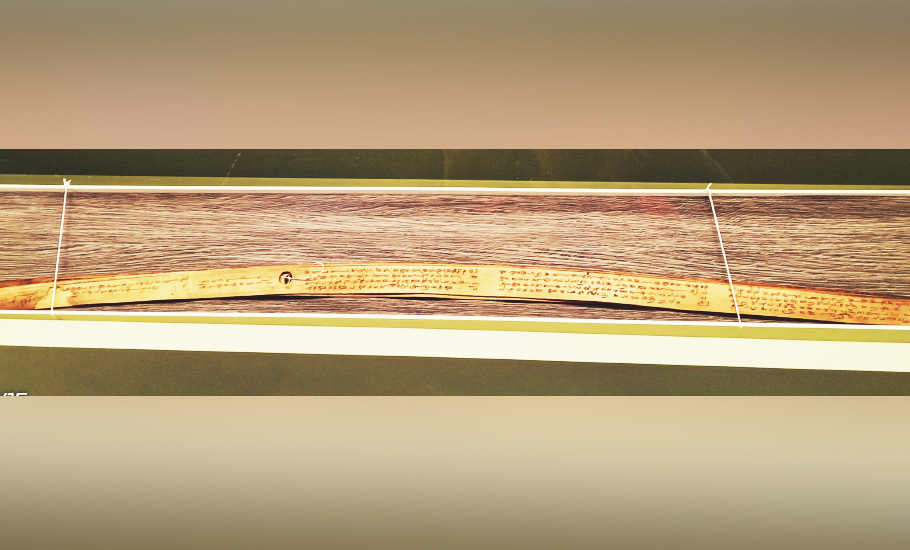

A museum where palm leaves tell the tale of ancient kingdoms

How do you create a museum with palm leaves alone – mostly of the same size and texture, illegible to the layman? It took a while for museologist-bureaucrat Venu Vasudevan to find an answer to the questifon. Even though the contents on the engraved palm leaves differed, their physical features remained the same. A mechanical display of the manuscripts would not make sense. He soon...

How do you create a museum with palm leaves alone – mostly of the same size and texture, illegible to the layman? It took a while for museologist-bureaucrat Venu Vasudevan to find an answer to the questifon. Even though the contents on the engraved palm leaves differed, their physical features remained the same. A mechanical display of the manuscripts would not make sense. He soon realised that the key was to create excitement and wonder from the contents of the palm leaves rather than the objects themselves. With a team of creative people, Venu went ahead.

In 2019, a team started transliteration of the ancient palm leaf manuscripts. Another team worked on the design and other aspects of the proposed museum. Despite Covid-induced lockdown playing hide-and-seek, the team could finish the work on time. The one-of-a-kind Palm Leaf Manuscript Museum was opened to the public at Central Archives in Thiruvananthapuram a month ago.

The museum presents a selection of manuscripts from the Central Archives, which houses one of the biggest collections of palm leaf manuscripts in the world. “There are galleries which outline the evolution of writing and the emergence of the Malayalam script from olden systems such as Vattezhuthu and Kolezhuthu. Through the eight thematic galleries, the visitor gets a glimpse of the complex administrative systems of land management, the path-breaking proclamations of the Travancore royals, international negotiations and agreements and documents that have become historical milestones,” said Venu Vasudevan, who is additional chief secretary (archives and museums) to the government of Kerala.

There are 187 engraved palm leaves displayed at the museum’s eight galleries. The oldest among them is a manuscript of AD 1249 with details about a Pandya king called Kashikanda Parakrama who built a temple in Tenkasi and sheltered people in that area. This palm leaf manuscript, engraved in Tamil, gives information about the rulers of south Kerala during the 13th century AD.

Like in most civilizations, the history of writing in Kerala also began with cave engravings. Malayalam, as a language, progressed through scripts such as Tekkan Brahmi, Vattezhuthu, Kolezhuthu, Mayanma, Grantha etc. With the discovery of writing on palm leaves, many ancient temples and ancestral homes started recording their daily activities. A collection of such palm leaf manuscripts was called ‘Granthavari’. Most popular among them are ‘Koodali Thazhath Tharavad Granthavari’, ‘Kozhikode Granthavari’, ‘Perumbadappu Granthavari’ and ‘Mathilakom Granthavari’. Although the idea of maintaining these Granthavaris was not to record history, they eventually became the primary sources of the bygone era.

The engraving on palm leaves makes use of different old scripts such as Vattezhuthu, Kolezhuthu, Malayanma and Grantha. The majority of the writings were in Tamil and Malayalam. All these scripts are derived from the mother script Brahmi which was widely used in South East Asia and Indian subcontinent. Scholars believe that south Indian Brahmi originated from northern Brahmi, which in course of time gave birth to Vattezhuthu, Kolezhuthu and Malayanma. Vattezhuthu is the most ancient script of Kerala which was widely used in issuing decrees and commercial transactions in Tamil.

The Palm Leaf Manuscript Museum is housed in the historical building which is situated at the north-west area of the fort heritage zone in Thiruvananthapuram. The building was a military barrack and it was later used as the prison of erstwhile Travancore until a modern prison was constructed in Poojappura in 1887. The building has been used as the headquarters of Huzur Vernacular Records (official archives of Travancore) since 1887. More than 10 million palm leaf manuscripts ranging from 13th century AD to 20th Century AD are stored here. This is perhaps the world’s largest collection of manuscripts, according to scholars.

Churunas (scrolls), ancient palm leaf granthas and single palm leaf manuscripts have been displayed at the museum. The most important leaf from a scroll is displayed with translations of the text into Malayalam and English. A magnifying lens is kept at the bottom of every palm leaf for those who want to read it. Manuscripts on copper plates, bamboo splints and paper records are also housed here. They form the oldest and most voluminous records about the history of erstwhile Travancore, Kochi and Malabar regions. There are land and revenue records, tax records, orders of the Diwan, land disputes, court judgements and orders, adoption and family pension, harbour records, import and export of grains and royal decrees. There is a separate section for Mathilakam records, the most significant documents on the famous Sree Padmanabhaswamy Temple in Thiruvananthapuram.

A palm leaf manuscript of an order denying permission for self-immolation in 1818 shows how progressive the king was. A permission to perform sati was sought by one Veeramma, widow of Sitaraman, in Kollam in 1818. The permission, however, was denied. Veeramma made a sit-in before the Hajur Cutchery, the old form of the current Secretariat, for a long period. She was sent back with her relatives after giving the announced compensation.

Empowerment of women was given importance in the 19th century. A palm-leaf manuscript in Malayalam in 1864 mentions allocation of funds for starting vocational centres for the sustenance of women. Travancore ruler Ayilyam Thirunal Balarama Varma allocated 300 rupees for starting an employment centre for women. The idea was to make women in Travancore self-sufficient by establishing shops.

A palm leaf manuscript records a significant offering to Thiruvattar Adi Kesava Perumal temple by Marthanda Varma, the legendary king of erstwhile Travancore. When the Dutch captured Colachel and established a fort there in 1741, Marthanda Varma decided to recapture it by waging a battle. He visited Thiruvattar Adi Kesava Temple and gave offerings to the god. After sacrament before the deity, the chief priest handed over the sword to the king. It was from here that Marthanda Varma set out to Colachel with his army.

“The battle of Colachel has an important place in history. This document is about the battle of Colachel. The Dutch were defeated in the battle of Colachel in AD 1741. The prisoners of war were sheltered at the Puliyoor Kurichi fort. With this victory, Marthanda Varma became the first Asian ruler to defeat a European naval force,” said Maya, a member in the team of translators of the palm leaf manuscripts.

The manuscript also reveals accounts of fascination for new products. In 1867, Christopher Latham Sholes invented the first practical typewriter and a keyboard layout. However, the typewriter found its way to Kerala in 1896 itself. The Kochi ruler accorded sanction to buy a typewriter for the use of the appeal court. A Yoder brand typewriter was purchased in 1896, with a cost of Rs 9,450.

King Swati Tirunal Rama Varma (1813-1846) was the first Travancore ruler to introduce the western system of education in the state to impart free English education. The king brought R B Roberts from Nagercoil to Thiruvananthapuram and started free school. This institution later became the famous University College. A palm leaf record of the appointment order issued to RB Roberts has been displayed at the museum.

We are used to domestic travel restrictions today, as we have had a tough time dealing with covid since 2020. However, a palm leaf manuscript reminds us of the travel restrictions imposed in 1819. “The record says that many died in Kochi due to an epidemic. More doctors were appointed in Travancore to initiate steps against the spread of the epidemic. They distributed medicines among the subjects. That was also the festival season in Aryankavu, Achankovil and Sabarimala regions. As a travel ban was imposed on the region, orders were issued to resume travel across the border. The restrictions were lifted as the pandemic spread was not so severe beyond the border and travel restrictions might affect trade,” said Smitha and Jaseela who with Maya translated the manuscripts into Malayalam and English.

Another palm leaf manuscript, engraved in 1862, shows the request of one Piyatha Thithayi Umma of Pokkakka Illam for getting her missing lease deed. The deed is about the land that she leased to Thrissur Vadakkumnathan temple at an amount of 31 ‘puthupanam’ (old currency). “She requests that if found, the lease deed has to be handed over to Thrissur Devaswom and the border of this land is recorded in this document. This is an important record of Hindu-Muslim religious harmony that existed in the 19th century AD,” said Smitha. Caste hierarchy, however, was at its peak those days. People belonging to Shudra, Ezhava, Channar and Marakkar were not allowed to wear gold and silver ornaments. A palm leaf manuscript of 1818 records a decree by the then queen Parvathy Bai by giving permission to all for wearing gold and silver ornaments.

The museum maintains a special section for the Mathilakom records of the famous Sree Padmanabhaswamy temple and the erstwhile Travancore kingdom.

The temple became famous for its vast wealth that counts to billions. The Mathilakom records are related with the upkeep of Sree Padmanabhaswamy temple. The state archives has a collection of millions of such records. “From this huge collection, some selected items are exhibited here. These are related with construction of the temple, Thippadidanam (surrendering the state to Sree Padmanabha), festivals, opening of the vaults in the temple,” said Jaseela.

King Anizham Tirunal Marthanda Varma (1729- 1758) dedicated the Travancore kingdom to Sree Padmanabhaswamy and the ruler became a servant of the deity. Known as “Thrippadidanam” in history, the whole area of Travancore became the land of the god. The palm leaf manuscript of 1750 displayed here details the area and the properties dedicated to the god. The palm leaf manuscripts were once a property of the scholars and academics. The trend has changed today, thanks to technological advancement. With videos and QR code systems, the Palm Leaf Manuscript Museum makes it accessible to laymen and researchers alike.