- Home

- News

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- World Cup 2023

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Premium

- Science

- Brand studio

- Home

- NewsNews

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Sports

- Loading...

Sports - Features

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium

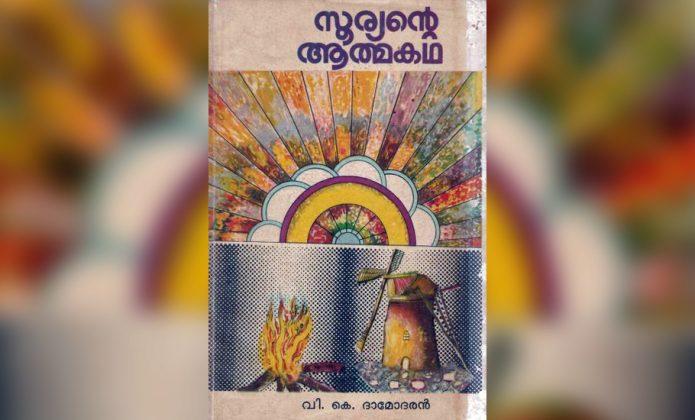

60 yrs on, how Kerala Sasthra Sahithya Parishad is igniting young minds

In the early 1990s, the chatter in the remotest villages in Hindi-speaking Bihar and Madhya Pradesh was interspersed with an unusual slogan – ‘Ernakulam jee uthega desh ke har gaon me’. The inspiration behind the slogan had come all the way from a literacy movement engineered by the Kerala Sasthra Sahithya Parishad (KSSP) in 1988-89. The rallying cry was a tweaked version of...

In the early 1990s, the chatter in the remotest villages in Hindi-speaking Bihar and Madhya Pradesh was interspersed with an unusual slogan – ‘Ernakulam jee uthega desh ke har gaon me’. The inspiration behind the slogan had come all the way from a literacy movement engineered by the Kerala Sasthra Sahithya Parishad (KSSP) in 1988-89.

The rallying cry was a tweaked version of the catchphrase that was heard during the communist-led Telangana peasant movement (1946-51), ‘Telangana jee uthega desh ke har gaon me. (A Telangana-like movement will come up in every corner/village).’

Started in 1962, the KSSP proved to be a transformative exercise for Kerala in building an inclusive and democratic society as it prompted people to question unscientific behaviour and archaic social practices. As it celebrates 60 years of its existence as a volunteer organisation, some are also looking at what the KSSP got wrong on the way and how it can stay relevant in the years ahead.

The Parishad caught the people’s imagination by making them understand the importance of learning to read and write, instead of being preachy towards the unlettered.

Why should an elderly person, who is in the last innings of his life, learn to read and write? What would he gain? Should people aim for literacy just because the government of India had a programme and funding to spread literacy? The KSSP answered all these questions and more.

The initial task was to help people understand how being lettered would help improve their lives along with that of their successive generations. How education is intrinsically linked to people’s relationship with the state and makes their access to constitutional rights easier. All this is ultimately connected to their well-being. The KSSP, through its countless volunteers, was successful in convincing people that literacy transforms life for the better.

The use of popular mediums such as street dramas, songs and dance performances to convey its message helped the KSSP emerge as an effective communicator. The organisation helped separate literacy from the idea of a bureaucratic exercise under which governments were duty-bound to raise literacy levels, and expanded it to a people’s movement.

Science for social revolution

The Parishad was born out of the need to popularise science. Articles on science hardly found space in the Malayalam publishing industry back then. The readers and the publishers loved fiction. Scientific discoveries, understanding and rational explanations remained confined to a limited circle of scientists and professionals. Those interested in writing on science had no way to get published.

That is why a group of young enthusiastic science writers gathered in Kozhikode in September 1962 to discuss the way ahead. The meeting resulted in the genesis of the Sasthra Sahithya Parishad aimed only at publishing articles on science, organising seminars and exhibitions with a select membership of science writers. The platform tried to avoid developing an hierarchical structure even though it had people designated as president and secretary.

To remain egalitarian, both leaders and members of the KSSP were bound by the same rules, they shared the same dormitories as well as the burden of physical labour required to run the operations. For instance, renowned nuclear engineer and educationist Dr MP Parameswaran lugged firewood to demonstrate the functioning of smoke-free stoves to people. He was among the leaders who helped design programmes organised by the Parishad.

Spreading awareness about smoke-free stoves was one of the most important projects taken up by the organisation. It demonstrated to people the importance of energy conservation and simpler ways to achieve it. The Parishad allowed a free flow of ideas by ensuring a democratic structure where everyone was allowed to put forth their ideas at equal footing.

The KSSP, which was formally inaugurated on September 8, 1962, was in fact the rebirth of Kerala Sasthra Sahithya Samithi, an association of science writers.

Renowned scholar and Communist party member PT Bhaskara Panicker, who played a pivotal role in Kerala’s first cabinet led by EMS Namboodiripad, was the one who had organised the Samithi. He was the secretary to the then education minister Prof Joseph Mundassery. The Sasthra Sahithya Samithi, however, did not last long and later reorganised as the Sasthra Sahithya Parishad. The inaugural event took place at Devagiri St Joseph’s College, Kozhikode.

The passion and imagination for the popularisation of the movement and to build a science-driven society is reflected in the first souvenir published the same year.

“Our desire is to educate the present generation, to have an aptitude for intellectual adventure so that a new generation may grow less fettered by the ‘gross and stupid superstitions of orthodoxy’. This is the only way for true science to fulfil one of the most beneficent functions, that of relieving men from the burden of false science.”

The slogan raised by the Parishad embodied what the organisation stands for – science for social revolution.

Catch ’em young, scientists on streets

The Parishad gained success by catching the imagination of young learners. Through songs, poems, dramas and storytelling, it could translate complex scientific and social issues into a simpler language that children found easy to grasp and comprehend. The Parishad formed balavedis (children’s wing) and science forums across Kerala through which thousands are introduced to the enthusiasm of learning science from everyday life. It succeeded also because the prescribed traditional school curriculum didn’t have similar scope.

Scientists and doctors going to the streets and talking to ordinary people about the environment, food, water, literacy and development was a unique experience for the masses. The tradition has lived on for 60 long years.

KK Krishnakumar, who has been associated with the movement since its inception, says the Parishad organised countless classes across Kerala. “In one such class, we were talking about the importance of preserving water and the relationship between nature and human beings. Suddenly, an old woman stood up and told me, ‘the lecture is very interesting, we learned a lot of new things. But son, we don’t have drinking water in our village. There are public taps, but they all run dry.’”

From that moment onwards, science became a matter of politics for the KSSP. “It was a great moment of learning. No matter how scholarly you are, real learning starts only when your academic knowledge is challenged by the core issues of the public,” adds Krishnakumar.

But beyond all that, what makes the Parishad distinct from similar organisations that work on education, public health, environment or governance and policy?

The Parishad helps people practice what they have learnt. “What I have tried to achieve throughout my life is social justice. Everyone has a right to get their due share of social justice,” says Jagjeevan, who made the Parishad his full-time job early in life and was a state-level office-bearer for long. Jagjeevan was also a member of KSU, the student wing of the Congress in Kerala.

Even though the KSSP is generally known to be a collective of Left-leaning people, anybody from any political party can join it. “No one has ever asked me to leave KSU. No one has ever challenged or questioned my political association. On the contrary, even the senior members like Dr MP Parameshwaran were not hesitant in entrusting youngsters like me with bigger responsibilities.”

The many achievements

Popularising science was not just about publishing articles on science in Malayalam and introducing scientific concepts to the ordinary people. It was also about educating people and making them aware of the misuse of science. Bringing environment to the centre of the debate was one of the biggest contributions of the KSSP. The movement against the contamination of Chaliyar river, the campaign against the pollution in Eloor, which was mapped as the most contaminated industrial belt in Asia, are among the projects undertaken by the KSSP.

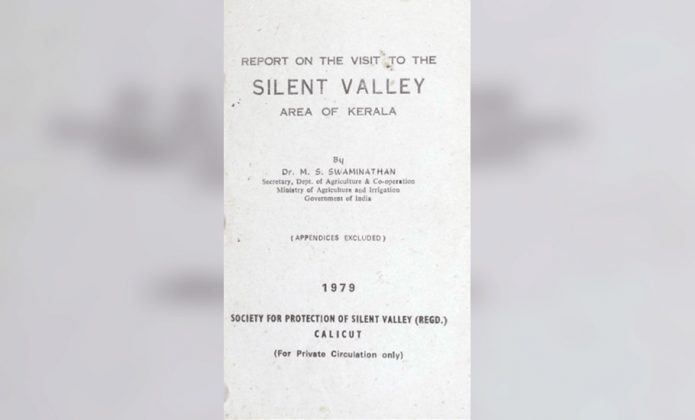

The historical struggle against the idea of a hydroelectric project in the Silent Valley rainforest was yet another landmark intervention organised and engineered by the Parishad. Members and followers of the Parishad travelled from village to village, demonstrated kalajathas (folk theatre), spoke to people and sold books.

The Bhopal gas tragedy was one of the triggers that helped the KSSP gain relevance in states beyond Kerala. The massive campaign against Union Carbide, the company which was responsible for the gas tragedy, spread like wildfire even among children. The call for boycotting the products of Union Carbide like Eveready battery saw a great response.

“I still don’t buy or use the Eveready battery. We all know the ownership has changed, but political perception is not just an idea. It’s a habit that you practice,” says Professor Anita Rampal, a scholar in science education and the former dean, faculty of education, Delhi University.

Anita Rampal does not clearly remember when and how her association with the Parishad began. “I was fascinated by the kalajathas organised by the Parishad. The Parishad was quite successful in striking a chord with people and their problems. Democratisation of science is the most vital contribution of the Parishad,” says Rampal.

The process of widening the organisation beyond the border of Kerala was a slow and spontaneous exercise. A collective of states, Bharat Jan Vigyan Jatha (BJVJ), took out massive rallies from states across India with the immediate trigger being the Bhopal gas tragedy of 1984 that sent a deep shock wave across the nation. The rigour of questioning the misuse of science created by the Parishad gained momentum after the worst-ever industrial disaster that the country had witnessed.

The five rallies reached Bhopal on December 2, 1988 – the fourth anniversary of the tragedy, a ground-breaking moment in the history of people’s movements in India. The All India People’s Science Network (AIPSN) was formed at the All India People’s Science Congress organised in Kannur in February 1988 inspired by BJVJ. AIPSN – a permanent platform with an objective to look at science from the perspective of the people – is a federation of like-minded science organisations from various states. Twenty six organisations, including the likes of Delhi Science Forum and Tamil Nadu Science Forum, participated in the Kannur conference.

“The ability to draw in a large number of people across party affiliations is the strength of KSSP,” Harsh Sethi, former consulting editor of The Seminar, who was part of the KSSP, tells The Federal. Sethi was associated with the KSSP 20 years ago. “I am amazed by the amount of knowledge produced by the KSSP and its capacity to popularise the same among people.”

The fact that the KSSP raised funds only by selling the books it published goes on to show its popularity. “There is no match for KSSP as a volunteer organisation. There were volunteer groups in India but were small in terms of participation and were led mostly by the charisma of some individuals,” he adds.

But no success story can evade scrutiny. The KSSP, too, is no different.

What KSSP has failed to do

Although the Parishad has published a plethora of leaflets, books and survey reports on the status of women in Kerala, the organisation could not address the deep-seated patriarchy, both in and outside the organisation.

“I remember one training programme I attended sometime in the 1980s organised by the KSSP. I knew that most of the elementary school teachers in Kerala were women. However, I was shocked to see the thin presence of women in that meeting,” says Prof Rampal.

Sethi, too, shares the same view. “The KSSP has to do a serious introspection on why it has never had women in their top leadership. It also failed in understanding the reality of caste in Kerala,” he says.

Prominent Dalit Scholar and writer KK Kochu couldn’t agree more. “Boycott calls as a mark of of protest was a powerful tool used by the KSSP, but have they ever asked for boycotting caste-based labour?” he asks.

According to Kochu, the KSSP pioneered ideas like preparing the resource mapping of every panchayat. But they failed in mapping the resources of Dalit communities in Kerala. “In other words they did not map the lack of resources for Dalits in Kerala.”

Kochu, who is also critical of the ‘conservatism’ towards environmental concerns maintained by the Parishad, adds that it never raised the question of the land ownership and nor cared to address the relationship between caste and land ownership.

“It has created hindrance in Kerala’s growth in the production sector. Their objection to the K-Rail project is the latest example,” he adds. (K-Rail is the dream project of the Left government that envisages to construct a high-speed rail network from Thiruvananthapuram to Kasaragod.)

However, many among the KSSP leadership are open to criticism. It does not deserve any mercy in this regard. It is a matter of shame that even after 60 years, the KSSP has very few women members as office bearers in their state and district offices. We need to learn and grow further and for that we need to have a fundamental shift in attitude,” says Krishnakumar.

Amid such criticisms, many can’t help but wonder whether the Parishad lost its past glory. Quite a few who grew up working with the Parishad or following its journey too feel so.

Behind time

“After a point of time, I believe the mainstream Left [CPI(M)] started ignoring the Parishad. This has happened because the Parishad stood against the party agenda in several contexts, especially in matters related to environmental issues,” says Jinoy Jose, former deputy editor of The Business Line.

Jinoy, who identifies himself as someone groomed by the Parishad, also thinks that it lacks the ability to catch up with today’s generation, especially those from urban areas and to cater to their aspirations.

“For a village lad like me, hailing from a lower-middle class Catholic family, the Parishad trained me to see the world from an entirely different point of view.” He says it introduced him to the world of books. “The balavedi during my childhood and the science forum in my teens nurtured rational thinking and a probing mentality, which laid the foundation of my growth to a career in journalism.”

He recollects a speech delivered by Communist leader Manik Sarkar at Irinjalakuda in Thrissur organised by the Parishad and its instant translation by late professor EK Narayanan, a scholar of physics. “That electrifying translation in impeccable English inspired me to learn English which I believe was a game-changer in my life,” says Jinoy.

Despite all that, what keeps the KSSP unique is its ability to learn and improvise. The leaders and members know that they have to go on a fast-track mode to catch up with the new generation.

“The young generation is well exposed to information technology. There is a need to understand their communication tools and to develop a methodology to talk to them,” says Krishnakumar.

While it does not mean that the KSSP has distanced itself from the current generation, the balavedis are active mostly among the rural children across the state. Neelambari Gireesh, a Class 8 student from Malappuram’s Kadambuzha, tells The Federal what she had recently learnt from the balavedi.

“We had an exciting time on the day of the annular solar eclipse [2019]. We all gathered in the school and observed the solar eclipse. We also came to know about the superstitions attached to solar eclipse. People usually say that we should not eat during an eclipse. But we all enjoyed food when the eclipse was happening to prove that it is only a superstition.”

This quest for rationalism is reflected well in the Parishad’s website regarding its membership process. Initially, membership was limited to science writers only. As the Parishad grew into a mass movement almost everyone was encouraged, albeit with a rider. “Those who do not respond to mails/letters, those who procrastinate, those who are unable to see the collectivity in work, those who do not trust in human talents and those who go for gossiping instead of constructive criticism. Everyone else is welcome,” says the KSSP website while explaining who ‘cannot’ be a member/activist.

Inspired by the Parishad, many learnt to question irrational beliefs. Take, for instance, the Parishad member KK Krishnakumar, who wrote a Malayalam song that was later translated to several languages. In the song, written in the early 1980s, he stresses on the importance of questioning and not taking anything at face value.

Tell Me Why…

A rainbow rises up there, and stars twinkle in night sky

Why, tell me why jasmines are white an’ hibiscus red

Flies not my little kitten unlike the creaky crow and pesky pigeon.

Why, tell me why, will you please?

Smugglers steal away all trees in our mountains, even as

Lesser mortals languish on streets, begging for daily bread.

Why my rivers are poisoned while caste and creed

Throttle and torture us humans; why, tell me why.

Why do we starve, and struggle with truth?

Why are there superstitions, why and why?

Ask, let us, loud and clear, head held high

Whenever injustice raises its ugly head

Why, why, why and why. Tell me why!