- Home

- News

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- World Cup 2023

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Premium

- Science

- Brand studio

- Home

- NewsNews

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Sports

- Loading...

Sports - Features

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium

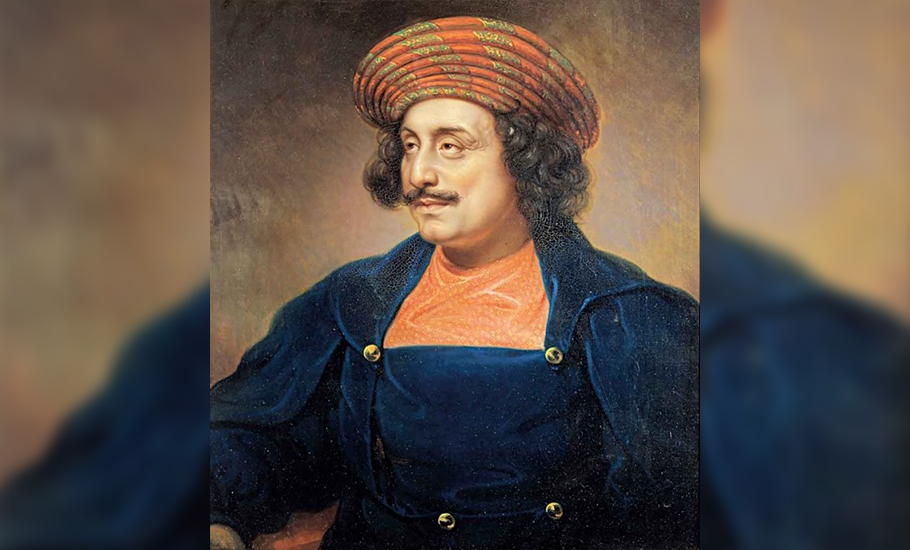

250 years later, what Raja Rammohun Roy’s legacy means today

As a pioneering modernizer of the Indian society, Raja Rammohun Roy was a tall figure. It is not without reason that Rabindranath Tagore called him the ‘Father of Indian Renaissance’ and the ‘Prophet of Indian Nationalism’. He was a harbinger of both socio-cultural renaissance and political nationalism. As the nation observes his 250th birth anniversary year, it is pertinent to look...

As a pioneering modernizer of the Indian society, Raja Rammohun Roy was a tall figure. It is not without reason that Rabindranath Tagore called him the ‘Father of Indian Renaissance’ and the ‘Prophet of Indian Nationalism’. He was a harbinger of both socio-cultural renaissance and political nationalism. As the nation observes his 250th birth anniversary year, it is pertinent to look at his legacy.

Early life

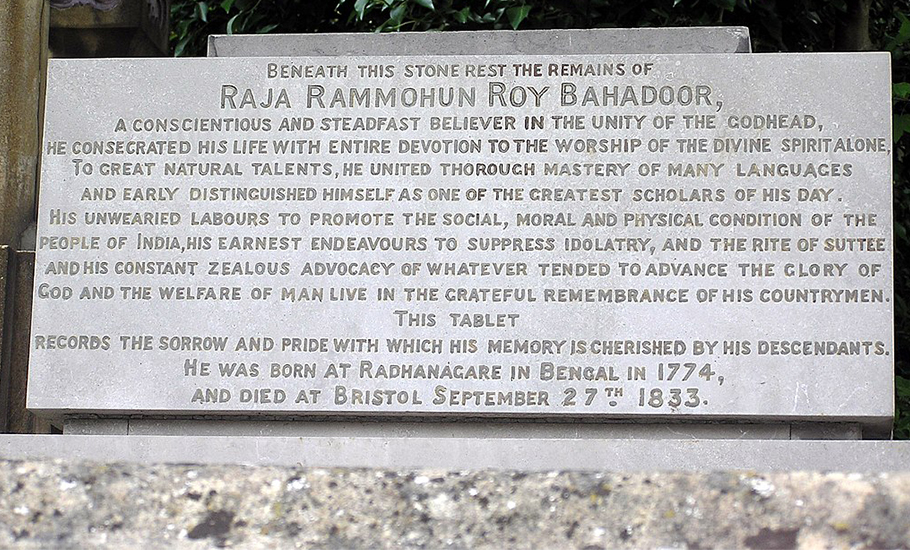

Raja Rammohun Roy was born in 1772 in a traditional elite Brahmin family in the Radhanagar village of Hooghly district of united Bengal. Tragedy struck his family when he was 17. His elder brother Jagmohan died and his sister-in-law Alkamanjari was forcibly placed on his funeral pyre and burnt alive as the practice of Sati was widely prevalent in 18th century Bengal.

The incident left a deep scar on the mind of Roy. This became a life-defining event for Roy who took to the path of demanding reforms. As he grew up, the trauma of the younger days turned him into a determined reformer against many forms of social evils prevalent in his day. By 1812, Roy was leading a successful crusade against Sati. The then Governor-General of India, Lord William Bentinck, passed the Bengal Sati Regulation (Regulation XVII) 1829 on December 4, 1829, which made Sati illegal in the whole of British India.

Championing women’s rights

Raja Rammohun Roy not only fought for a widow’s right to live after her husband’s death, he also launched a crusade for widow remarriage and for upholding the dignity of women in general. He argued that women’s inferior status in society was because they had never been given an opportunity to socialise and get educated. They were deprived of a public life as well as professional life. He came down heavily upon the male-chauvinist society saying that men who cheated their wives outnumbered the cheating wives by ten to one.

Polygamy was widely prevalent among elite feudal families of Bengal in those days. Men would not come to meet their wives for months together. Rammohun Roy squarely posed the question: If women are of loose character, how is that even in such conditions they lived in the joint family taking up all the family responsibilities without any complaint even if they are ill-treated and subjected to domestic violence? Almost a century before Periyar EVR of Tamil Nadu, Roy had emerged as a similar sarcastic opponent of masculine sexism.

Pointing out the hypocrisy of the prevailing social order, Roy rhetorically asked why when the husband was poor the wife did double the amount of work to help sustain the family, but when the husband started earning better and got rich, he got married to another woman.

In a very orthodox society of 18th century, where the orthodoxy even enjoyed religious sanction, it was a grim battle for Roy and his fellow pioneers to usher in a dignified life for the loving and caring womenfolk of their own households. Roy did not limit his crusade to Sati abolition and widow remarriage only. He also campaigned for women’s right to education, right to employment, and right to property.

Broader reforms plank

Again, he did not limit his reforms campaign to the issues of women’s rights only. He strove very hard to promote modern education in general, for both men and women. The modernising impact of education would also be humanising, Roy believed. His reforms campaign was directed against the oppressive features of the caste order and superstitions in all religions.

Roy was sent to Patna to study Persian and Arabic at a young age. After a study of Koran, Bible and Sufi literature, he turned against polytheism and idol worship. Due to this, he developed differences with his father and had to leave home. He went to Tibet to study Buddhism. From there he went to Varanasi to study Sanskrit and Jainism. Back in Bengal, after a brief stay in Murshidabad and Rangpur, he moved to Calcutta, where he started learning English.

Roy established Atmiya Society in 1814 in Calcutta to fight against superstition, idolatry, caste rigidities, and meaningless rituals in all religions. Since he became a proponent of oneness of God, he earned the opposition of the orthodox in all religions. On August 20, 1826, he established Brahmo Samaj, a reform outfit in which he rallied many prominent reformists like Dwarakanath Tagore, Debendranath Tagore, and Keshub Chandra Sen.

And he always promoted Hindu-Muslim unity and a syncretic culture in Bengal which thrives even today despite the violent division of Bengal brought about by history.

Rammohun Roy did not limit his crusade only to social reforms. He also waged a concerted battle against the colonial rule. Not many know that even a few decades before the first expressions of economic nationalism appeared in the writings of Dadabhai Naoroji and Ranade among others, it was Roy who articulated the concept of colonial drain. He was the first to coherently argue that lack of development and industrialisation in Indian society was because of the huge drain of surplus from Bengal to England. He even concretely worked out the near-exact volume of the drain those days in quantitative terms.

Early colonial modernity vs late colonial modernity

While evaluating Roy’s contribution to the modernisation of Indian society, it needs to be underlined that the modernity triggered by British colonialism was early colonial modernity, the nascent and fledgling one when the urban middle class formation with modern education had just started taking shape unlike late colonial modernity after the reasonably broader development of indigenous capitalism and a numerically larger middle class that acted as the social base of advanced modernity.

The early colonial modernity was quite complex. The native champions of the early stirrings of modern values in life faced an acute dilemma. On the one hand, the modernity spawned by the Enlightenment project, had an epochal attraction, not only in Europe but also in the backward colonial setting of India. On the other hand, since England symbolised the last word in European modernity then, it was also seen as something associated with the enemy rulers.

In Europe itself, there was a dark side to the modernity that dawned with Enlightenment. From the early cruel colonial conquests and genocides, to the later-day fascism and wars, some ugly facets were also seen as the logical culmination of the seamy side of modernity. Some in India wanted to shun that modernity altogether. Others wanted to embrace it to fight the enemy better.

Roy even engaged with the colonial authorities, and cooperated with them in ushering in reform legislation like Sati Regulation and Child Marriage Act.

Years in England

After working briefly for East India Company, Roy started working for Akbar Shah, a descendent of the Mughal rulers, who gave him the title of Raja. Akbar Shah sent him to England to make a case for an increase in their privy purse.

Roy’s fame as a reformer of the Hindu society had travelled to England even before he went there in November 1830. Thanks to his stature, he was warmly received by the royal family as well as philosophers like Bentham and other intellectuals. The authentic home-bred Indian liberal was eagerly courted by the prominent British liberals. There he lobbied with the British government to ensure that the attempts of the orthodox Hindus to overturn the Sati Regulation did not succeed. In 1833, he died in England due to meningitis at the age of 61.

His eventful life established him as the foremost reformer of Indian social life in the early colonial period.

The early decades of the 19th century are often described as renaissance years in Bengal. As one of the early pioneers of that age, Roy had exerted a lasting influence on next generation stalwarts like Debendranath Tagore, Rabindranath Tagore, Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, Kazi Nazrul Islam, Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay, Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay, Michael Madhusudan Dutt, and even Swami Vivekananda. All of them respectfully acknowledged that impact.

A fond remembrance as well as revisiting the works of this reformist Hindu philosopher who symbolised a syncretic culture is of high contemporary value in today’s polarised India.