Scepticism towards Hindu religious subjects is passe; Bali art shows the way

Modern artists in India take an ‘oppositional’ position vis-a-vis religion; in Bali, public monuments and modern art draw copiously upon Hindu motifs, with no subversion in evidence

This piece is especially relevant because of the controversy around the Kaali posters and Mahua Moitra’s subsequent defense of documentary filmmaker Leena Manimekalai. I don’t have much to say about the controversy itself but a recent trip to Bali sparked off some thoughts on how the Hindu religion is represented differently by artists in Bali and India.

A question is why modern artists in India take a more ‘oppositional’ position vis-a-vis religion than their contemporaries in the Indonesian island. The poster for Kaali – notwithstanding Moitra’s wholehearted defence – is not viewed as ‘neutral’ towards the religion and the same was true of the work of progressive artists like MF Hussain, who invited the wrath of the Hindu right-wing through their provocative treatment of mythological subjects.

Also read: How far can dharmic principles sustain India as a Hindu rashtra?

In Indian literature, the modern tendency too has been to be sceptical towards Hindu practices as in UR Ananthamurthy’s Samskara – as the only legitimate ‘modernist’ approach. In India also, where high art has taken the subversive or sceptical approach, popular art – as in a mythological film or Raja Ravi Varma’s lithographs – has been more attuned to public attitudes towards belief.

Hinduism in Bali

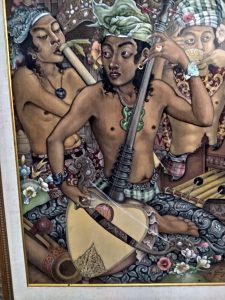

In Bali, on the other hand, not only do public monuments show Rama with his bow and Ghatothgacha battling Karna but the modern art exhibited in museums also draws copiously upon Hindu motifs, with no subversion in evidence. Since high art and literature are by their nature products of elite culture, we may surmise that the sceptical/oppositional attitude towards Hindu religious practices belong to that class in India. The term ‘elite’ is not a denigration of the class since high art is largely in its custody, in any culture.

To speculate upon the creation of the artistic /literary elite in Independent India, one must take into account the Hindu-Muslim conflict that led to the horrific violence in 1947. It will be controversial to inquire into whether Muslim invaders/monarchs in India treated Hindus fairly but the treatment could not have been evenhanded, given such animosity in 1947.

With India and Pakistan going their own ways and India opting for secularism, there was a concerted attempt in the Nehruvian era to neutralise Hindu majoritarianism; part of the design was to inculcate rational attitudes towards religious belief through education. The protection of the minorities and tolerance of their beliefs were also part of this ‘secularist’ credo.

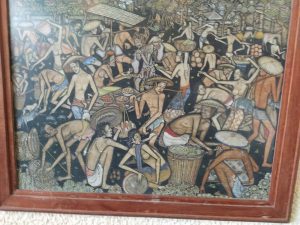

Bali art: Bhima in exile as cook shopping for provisions

Also read: Politics of food: Practice, not texts, determines Hinduism

The liberal class in India is a product of this education system but we can surmise that rational attitudes towards religious belief/practice hardly percolated as far down as the system hoped. This is substantiated by the fact that many more Indians cherish mythological films, or hang up pictures of gods by Raja Ravi Varma in their homes than visit museums or read modernist literature.

Nehru’s take

Nehru tended to see all traditional attitudes among Hindus as essentially retrogressive or ‘communal’, although the Congress party had traditionalists in its ranks (as also socialists) who had Sardar Patel’s support. With Patel’s death Nehru held sway but without being able to render the majority of Hindus ‘modern’ and liberal/rational attitudes, found domicile in a relatively smaller – though vocal – proportion of the public.

To call Nehru ‘anti-Hindu’ is unfair, but he was westernised while the majority – including those of the other religions – clung to their religious beliefs. Nehru focused on Hinduism in his rationalist/ modernising efforts but he perhaps only followed the expectation that if one reforms oneself first, the others will naturally follow.

There has consequently been an enormous gap between the liberal’s attitudes towards religious belief and those of the more tradition-minded majority, and this is now manifested in the public space as political discord. Hinduism does not proselytise but cultural policy after 1947 evidently underestimated its strength among its adherents; and that is what the Hindu right-wing, long shunned as a political pariah by liberal-minded people, has gradually taken advantage of.

This leads us to the question of what the relationship between ‘high’ and the ‘popular’ in the arts is and whether there can be such a yawning political gap between the two as in India. I have tried to speculate about the use of Hindu motifs and trace the ‘oppositional’ perspective taken by high art in India to cultural policy.

Art and religion around the world

The arts around the world teem with religious subjects and that is true not only of the popular but also of high art and literature – from Picasso to Dostoyevsky – and there is no reason for India to be so different. Even in India, Christian-born artists like Souza treat Jesus with more veneration than is granted to Hindu subjects – since Christian motifs have a value that modernity has not undone.

Evidently, there can be no guidelines for how artists or writers should approach Hindu motifs but I believe that the sceptical/oppositional attitude towards Hindu religious subjects in India has outlived its usefulness.

There is another danger lurking ahead, which is that high art and literature, by not engaging with the Hindu religion in all its complexity but simply taking an irreligious attitude towards it, is tacitly allowing a horribly simplified version to take over the public consciousness.

It could be argued that high art is not qualitatively different from the popular but only attempts to bring sophistication and depth to public attitudes. If this is allowed, the best kind of art in India could help a ‘truer’ version of Hinduism than the over-simplified one gradually gaining ground, and that would also serve a worthy political cause. Surely, artists using Hindu motifs can come up with work that will not immediately be dubbed an ‘insult to the religion’!

Hinduism is exceedingly complicated and that should be an incentive to artists and writers to also produce complex works that draw positively upon the religion and its mythology. That way they could re-establish contact with the general public that they could have lost.

(MK Raghavendra is a writer on culture, politics and cinema)

(The Federal seeks to present views and opinions from all sides of the spectrum. The information, ideas or opinions in the articles are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Federal)