NRC makes refugees from East Pakistan become stateless twice

On a sunny Tuesday afternoon, Sachin Barman (64), and seven of his neighbours were waiting at the revenue circle office of Chaygaon in Karmrup district. Their objective was to meet the circle officer and seek permission to hold a protest, over the National Register of Citizens (NRC) list, in front of the deputy commissioner’s office of the district.

However, the woman officer who encountered them at the entrance of her office room said she cannot listen to them as she was about to leave for an NRC meeting with the deputy commissioner.

“Sarkar apunarlukor lagat ase. Sinta nakariba… protest koribo nalage (The government is with you… don’t not worry and there is no need to protest),” she said when Barman quickly explained his grievance. However, they were asked to come the next day.

With an anxious and hopeful voice, he said, “Hopefully tomorrow we might get permission to hold the protest. This is very urgent. We have been holding meetings among ourselves and have decided to take a series of protest against the NRC list.” Barman is a Hindu refugee migrated from East Pakistan in 1964 to India.

Riots of 1964 followed by the India-Pakistan war in 1965 and then the Bangladesh liberation war in 1971 caused three huge waves of migration of Hindu refugees to India from East Pakistan. According to reports, an estimate of 6.7 million Hindus were forced to take refuge in India. A huge chunk of these refugees is spread over the North-eastern states of Assam, Meghalaya, and Tripura.

Sachin Barman lives in a refugee camp known as the Bamunigaon Permanent Liability Centre in Chaygaon area of Kamrup district along with over 3,000 inmates. The camp was established by the Assam government in the 1960s.

What’s in a name?

Puzzled as to what is next, Shyamapada Chakravarty, father of two daughters, says, “Our life is over. But we are worried about our children. Where will they go and what will they do? If they are not regarded as citizens who will give them work?” Like a thousand other Hindu refugees living in Bamunigaon, Chakravarty’s family also could not make it to the NRC.

“I was ten years old then. In the year 1965, I entered India along with my parents and a brother. Hundreds of people in Cachar district,” he recalls. Chakravarty was talking about the time when lakhs of Hindus from East Pakistan faced religious persecution and migrated to India.

The Indo-bangladesh border is the fifth-longest land border in the world with a stretch of 4,256 km. Assam shares 262 km of it in Cachar, Karimganj district in southern Assam in Dhubri, and South Salamara district in western Assam.

In 1969, the Ministry of Rehabilitation issued a refugee certificate to Chakravarty’s family. According to a cut-off date (March 24, 1971) decided based on the Assam Accord, like a thousand others, Chakravarty’s family was also entirely dependent on the Refugee Registration Certificate to prove their arrival. According to the accord, everyone who entered the state after the midnight of March 24, 1971 – when the Bangladesh War began – would be declared as an undocumented migrant.

Sachin Barman the man who was waiting for approval in the Chaygaon Revenue Circle Office, also crossed the border four years before Chakravarty did. Then eight-year-old Barman used to work as a daily wage earner in Guwahati, the capital city of Assam, 60 km away from the refugee camp.

“I remember crossing the border in Meghalaya and enter Goalpara district with 600 other people. We had faced lots of torture in that country (East Pakistan), here also people call us Bangladeshi though Bangladesh was formed much after my arrival. Now, if India does not consider us as its citizen, it is better we die,” said Barman. Barring the daughters-in-law, no member of the 257 families living in Bamunigaon Permanent Liability Centre is enlisted in National Register of Citizenship.

In another refugee camp in Cachar district, an approximate of 13,000 people are out of NRC. The Tapoban Nagar Refugee camp houses over 15,000 people belonging to mainly fishing community. Cachar shares a 32-Km international boundary with Bangladesh.

“Out of the 15,000-20,000 people living here since the 1960s, not more than 2,000 have made it to NRC,” claimed Ratan Das, a rickshaw Puller living in the area for the past 50 years. He makes anything between ₹50 to ₹100 per day. “These days no one likes to ride on the rickshaw of a Bangladeshi. Sometimes we get ridiculed for asking the legitimate fare. People scold us using the word Bangladeshi as slang. Now that we are officially outsiders, making a living will be very difficult for us,” says the 65-year-old, who is survived by his wife and three sons, who are also out of NRC.

Nearly, 200 km away from Guwahati, another refugee camp in Derapather area in Nagaon district, shares the same tale. Over 3,000 people, belonging to the Rabha, Hajong, and Lalung tribe are considered as the ‘son of the soil’ have been left out of NRC.

In another refugee camp in Matia in Goalpara in western Assam, almost 2,000 people from the Rabha and Bengali community have their names missing in the citizenship List.

Why refugee certificates are refused

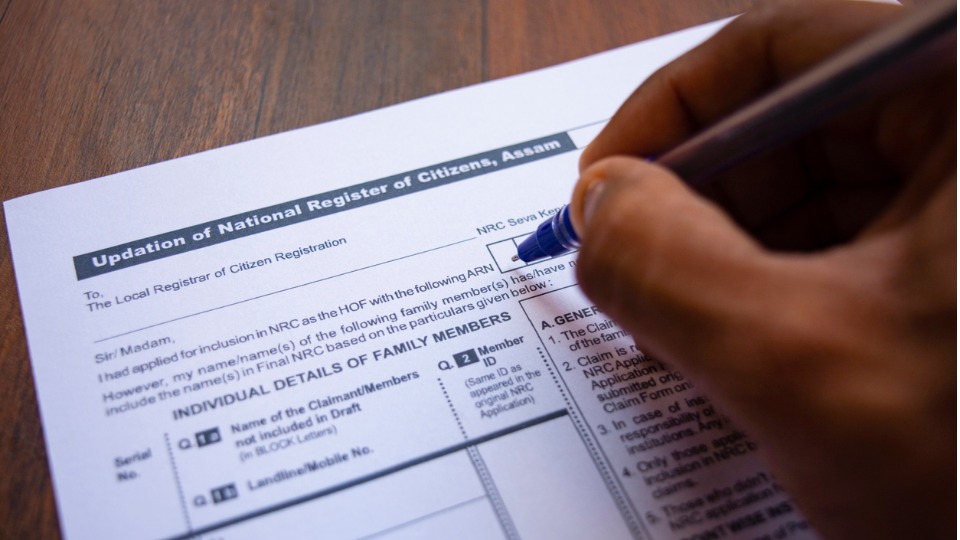

Thousands of refugees in Assam relied on their refugee registration certificates to claim their legacy in Assam. The Supreme Court had also approved the document as a legal one to claim citizenship.

However, a look back to 2018 shows that these certificates as a legal document of citizenship have been always confusing for the NRC officials. After the NRC authority, on May 2018, issued an intra-office memo advising the officials not to accept such certificates unless it is “absolutely confirmed about the genuineness”.

This move came as the NRC authorities felt that many illegal migrants with forged documents, listed their names in the partial draft NRC that was released on January 1, 2008.

A NRC official said, “As many as 100 refugee certificates were rejected by the NRC officials in Kamrup district saying that they are not credible as the government does not have any backend record to check the authenticity of these certificates.”

In October 2018, Prateek Hajela, the State Coordinator of NRC in Assam, filed an affidavit in the Supreme Court suggesting the drop of Refugee Registration certificate along with four other documents listed as valid proof of citizenship. In his report, Hajela stated that only ten documents out of the 15 listed earlier can be relied upon for inclusion of the names in the NRC, subjected to the authenticity of the documents verified by the relevant issuing authority.

Following his report, the SC had on September 5 allowed usage of any one of the 10 of the total 15 documents provided in List-A to claim the form to be used by the claimants for proving legacy.

The main reason why refugee certificates are seen as doubtful documents is because the government of Assam does not have any backend data to check the authenticity of it. In most of the cases, the reason for rejection in NRC against one is mentioned as “documents not satisfactory”.

Of promises and despair

Three months after India’s Independence, the Congress working committee on November 25, 1947, adopted a resolution which said, “The Congress is bound to afford full protection to all those non-Muslims from Pakistan who have crossed the border and come over to India or may do so to save their life and honour,” as quoted in India’s Struggle for Freedom: Select documents and Sources.

Jawaharlal Nehru, in the Parliament on November 5, 1950, said, “The Hon. Member referred to the question of citizenship. There is no doubt, of course, that those displaced persons who have come to settle in India are bound to have the citizenship. If the law is inadequate in this respect, the law should be changed,” as quoted in Jawaharlal Nehru Selected Speeches: Volume-2: 1949-1953.

“When Nehru gave us the refugee certificates why the state government did not keep its copies? We have kept our refugee certificates by wrapping in plastic bags and under the trunks for the past 50 years. Floods came, ethnic violence erupted, but we protected our documents. Why could the government not do it?” questioned 70-year-old Harekrishna Das, a refugee from Bamunigaon Permanent Liability Camp.

Abhijit Sharma, whose petition in Supreme Court in 2009 led to the entire exercise of NRC said, “Names of many Indian citizens who migrated from Bangladesh as refugees prior to 1971 have not been included in the NRC because authorities refused to accept refugee certificates.”

Amidst all these voices, the BJP is supposed to table the Citizenship Amendment Bill, in the winter session of the Parliament – a bill that seeks to make Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jains, Parsis and Christian immigrants from Afghanistan, Bangladesh and Pakistan eligible for Indian citizenship. Now, it has been considered as the way out to provide citizenship to these refugees.

“The border was open, the Indian government welcomed us by building refugee camps. Our families got lands from the government as well. And now the same country has made us stateless,” laments Barman, while waiting for permission to protest against being stateless twice.