In Myanmar, generals turn brutal as resistance intensifies

After failing to control protests demanding Aung San Suu Kyi's release and restoration of the parliament, the military moved into brutal mode opening fire with live ammunition in seven cities across the country last weekend.

Myanmar’s all-powerful army ‘Tatmadaw’ has started doing what it does best — shoot its own people.

After failing to control protests demanding Aung San Suu Kyi’s release and restoration of the parliament, the military moved into brutal mode opening fire with live ammunition in seven cities across the country last weekend.

UN Human Rights office confirmed 18 deaths in the February 28 firings with at least seven killed in the southern coastal town of Dawei, venue for a major Japanese-sponsored Special Economic Zone (SEZ). But far from being subdued, the killings led to a surge of people joining the demonstrations.

A Burmese military colonel, who attended his staff college in India, once told me that his generals had a simple formula to quell uprisings — shoot to silence and shoot more if it does not work. This reminds of East Pakistan martial law administrator Lt Gen Tikka Khan in 1971 — “kill a few lakhs Bengalis if they revolt and kill more if the revolt is not silenced.”

On Wednesday (March 3), the military upped the ante, opening fire in one-time capital and commerce-culture hub Yangon and then in six other cities. At least eight died in Mongywa, the capital of the Sagaing region, bordering India. Similar casualties were reported from Yangon, Pyay, Mandalay, and other cities.

The UN Human Rights Office in Asia confirmed at least 38 deaths during the mayhem on ‘Black Wednesday’, saying at least 54 people have so far died, 170 injured and more than 1,700 arrested.

The military may take comfort from the fact that the demonstrations have been largely concentrated in the towns and cities and not yet spilled over to the villages. But they are already having to reckon with administrative paralysis — policemen, government officials, bankers and businessmen are all deserting the military-backed State Administrative Council (SAC), shutting down shops and showrooms, banks, and financial institutions.

The army may still resort to greater force but as TV anchor Thida Moe told me recently: “The world has come a long way since 1988 when the last coup happened. The army just cannot repeat what they did then, killing thousands, because it all hits the social media in no time. A massacre like 1988 will provoke the global community into action. Even China which has backed the junta cannot back the Tatmadaw blatantly.”

Related news | Myanmar rebel group’s asylum request can put India in a dilemma

Thida was right — even after the Wednesday killings, protesters continued to swarm the streets in Yangon, capital Nayphidaw, Mandalay and other cities, and China seemed to get cold feet.

The military-backed SAC got a huge slap on its face when Myanmar’s UN envoy Kyaw Moe Tun openly pitched for global support to restore democracy in Myanmar. The SAC fired him and appointed his deputy Tin Maung Naing this week but Naing resigned after Wednesday’s killings and said his boss Kyaw Moe Tun was ‘still the ambassador’. The SAC has failed to appoint a new UN envoy and Kyaw has petitioned the UN to recognise him as the legally appointed envoy of the Myanmar government and de-recognise the SAC as ‘illegal’.

Kyaw is continuously meeting US, EU and ASEAN diplomats in a determined bid to step up the diplomatic offensive to force the military to restore parliament. A French diplomat described Kyaw as deposed leader Suu Kyi’s “best trump card on the global stage.”

On the day Kyaw’s revolt at UN held the centre-stage in the world body, Burmese policemen from border check-posts started fleeing into India’s Mizoram state, turning the spotlight on the military’s failed repression campaign which was only leading to uncomfortable spillovers.

The military-backed SAC, in an attempt to pacify the ASEAN, accepted 1,084 Rohingya Muslims back from Malaysia by sending three navy vessels.

The SAC also seems to have indicated that they may take back 81 Rohingyas stranded on a leaky boat in India’s Andaman islands after they sailed from Bangladesh’s Cox’s Bazar on February 11. It’s a different issue that the Rohingyas and the global rights groups including UN will raise a huge hue and cry if India sends these Rohingyas back to Myanmar since Bangladesh has refused to take them back.

Related news | UN envoy calls for release of Aung San Suu Kyi and other Burmese leaders

Since India has also called for ‘orderly democratic transition’ in Myanmar without raising the pitch against the Burmese army, which is seen as an ally to fight Northeastern rebels based in the jungles of Sagaing, the only real support for the military junta comes from China.

Suu Kyi’s NLD government also could not ignore China and had to clear all major Chinese projects (except scaling down the Kyaukphyu port and SEZ and not allowing the Chinese to resume work on the controversial $6 billion Myitsone dam in Kachin state).

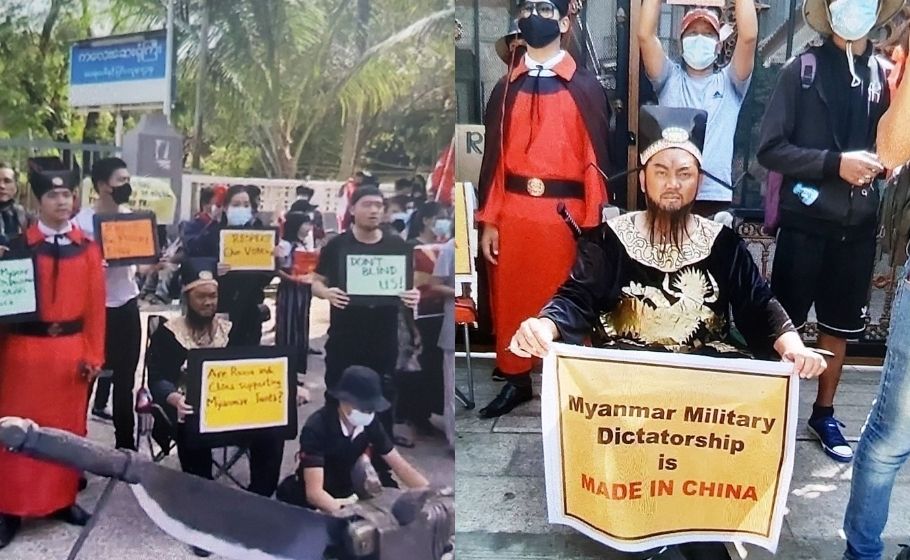

But Beijing reckons that the Burmese military, though suspicious of Chinese backing of the Wa and Kokang rebels up north, will be all the more dependent on it due to the inevitable global isolation as in 1988-89. No wonder, the pro-democracy protesters are flaunting placards: “Myanmar Coup: Made in China.”

But unlike 1988-89, when China itself was reduced to an international pariah after the military action at Beijing’s Tiananmen Square, the country now aspires to superpower status and must project itself as a responsible power on the global stage.

With its handling of the COVID-19 crisis impacting very adversely on China’s international image, Beijing can ill afford to be seen as the sole and principal backer of a brutal military regime which is killing its own citizens like flies. On the day the protesters flaunted placards holding China responsible for the coup, the foreign spokesperson in Beijing sent out a mild message for “return of stability through dialogue” in Myanmar.

The Burmese army may have their own motivation for the military takeover but if China stops backing them strongly, the signal will go out to the West and Myanmar’s neighbours, India and ASEAN, and the global push for return to parliamentary democracy will intensify.

That is exactly what the NLD politicians, now in jail or house arrest with Suu Kyi, or the Burmese protesters on the streets of Yangon and Mandalay are hoping for — a furious global push to bring down the SAC and bring back the parliament.

Related news | The sanctions game and Myanmar: Will it work?

The US has already started pushing China to work on the Burmese military to step down, even as it sanctioned some generals. State Department spokesman Ned Price said in a statement that the US’ Biden administration has asked China directly to “use its influence with the Burmese generals” to bring an end to the crisis.

The options before the Burmese military is clearly limited. It cannot resort to the 1988 type massacre of thousands to quell the uprising, the Burmese people have tasted democracy and they know the world is watching, so their will to fight it out on the streets remain undiminished by the killings over the last one week.

China may not be able to shamelessly back the SAC as it backed the junta in 1988-89. In that case, India and ASEAN will have lesser compulsions to look the other way and may join the West in raising the pitch for a restoration of democracy. The Islamic World, upset with Myanmar for its treatment of the Muslim Rohingyas, will bay for blood — ever-greater sanctions against Burmese generals and more pressure to accept Rohingya refugees back as one of 135 registered races of Myanmar.

Already world rights groups are raising the pitch for an arms embargo on Myanmar, something that impacts the military. So the Tatmadaw’s decision to keep parliament in suspension for one whole year by exercising its Emergency powers looks difficult. They may resort to a drastic change in electoral rolls in a few months, call for fresh elections, unleash a crackdown on NLD and hope Suu Kyi will not return with the kind of landslide that she got in November 2020. That will weaken her capacity and resolve to amend the 2008 military-drafted Constitution and help the military retain the 2015-20 status quo.

The generals will also have to reckon with a possible revolt in the lower ranks of the army — a crackdown in Burmese-dominated cities means the soldiers are possibly having to shoot at their own brothers and sisters. That may not be acceptable to a new generation of soldiers and officers who aspire to a powerful and professional army but not one that waste its energies in trying to run the government. After all, the Bangladesh effect may be rubbing on to the Burmese army.

(Subir Bhaumik is a veteran BBC and Reuters correspondent who has worked for Mizzima Media in Myanmar as Consulting Editor)