Tamil film legacy disappearing into a blackhole

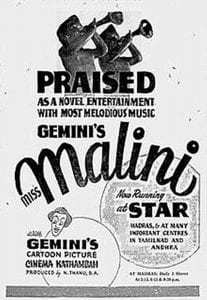

Recently, a group of history enthusiasts in Chennai, on a Facebook group that engages in conversations and exchanges information about all aspects of the city’s history, wondered about the whereabouts of the film ‘Miss Malini’. Was it available on YouTube? Did anyone have a copy of it, in any obscure format?

The film, released in 1947, was produced by Gemini Studios and directed by Kothamangalam Subbu. It is considered a landmark film for many reasons. It was the only movie for which the renowned writer RK Narayan wielded the pen as a story writer. The charlatan in the movie, called ‘Sampath’ (played by Subbu), became a recurrent one in his future works and novels like ‘Mr Sampath – The Printer of Malgudi’ and ‘The Guide’. The movie starred Gemini Ganesan in his debut role, albeit a minor one, while Pushpavalli played the title role.

Everyone wondered how, in the day and age of digitisation, an iconic movie can get lost. However, like one of them pointed out, ‘Miss Malini’ was not the first or the last movie to get lost. Some of the finest and landmark works in Tamil cinema have met with a similar fate.

Documenting the lost legacy

Sugeeth Krishnamoorthy likes to call himself an agriculturist based in Cumbum, Theni. While he indulges in the green field sowing and reaping, living the elusive dream of urbanic youngsters, catching up on the latest films and web series, he is also an off-beat film aficionado who keeps looking for the remnants of a forgotten flick, trying to unearth them  from archives. Having worked on a documentary ‘The Missing Reels of Thamizh Cinema (1916-2016)’, Krishnamoorthy is filing an RTI appeal seeking the status of several Tamil films that were sent to the National Film Archives of India (NFAI).

from archives. Having worked on a documentary ‘The Missing Reels of Thamizh Cinema (1916-2016)’, Krishnamoorthy is filing an RTI appeal seeking the status of several Tamil films that were sent to the National Film Archives of India (NFAI).

Krishnamoorthy says the extent of loss of reels could be measured from how of the 100-odd films made in the silent era (1916-1934) only one survives till date from the South. Even the first film of the era, ‘Keechaka Vadam’, released in 1916, directed by R Nataraja Mudaliar, has gone down the annals as a lost film.

He explained, “However, ‘Marthanda Varma’ (1933) survived because of a copyright dispute and it is considered to be a Malayalam film as it presented the Malayali culture. It was found locked up in a book depot by none other than the legendary filmmaker Adoor Gopalakrishnan who took the initiative to preserve it in 1964. The other film was a Christian propaganda film called ‘Catechist of Kil-Arni’ by a priest called Thomas Gavan Duffy in Thindivanam. He has chronicled the life of people in and around the place.”

He added that ‘Pavalakkodi’, which starred the first superstar of Tamil cinema MK Thyagaraja Bhagavathar in his debut film, and was directed by K Subramanyam, and ‘Sati Sulochana’, are the oldest known surviving films. Incidentally, both were released in 1934.

How were they lost?

However, while one can blame the lack of technology for the films being lost, experts opine that the nature of the reels were largely the reason. Film historian Theodore Baskaran said, “Britishers were concerned about their films and they didn’t give much importance to indigenous films made during the silent era. However, after the talkies took over, the films received an exclusive marking — Tamil, Telugu, etc — so they couldn’t compete. Yet, till 1940s, the industry never got any support from the government. Even Gandhi, Rajaji, and Periyar condemned cinema. It was Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s initiative to set up an institute promoting films in the 1960s. Contrast this with the Soviet Union’s support that resulted in works like ‘Battleship Potemkin’.”

Nitrate-based reels crumbled and self-destroyed in hot and tropical climate. He cites space constraints as another reason. “After the films had one run, the reels were destroyed for extracting the silver in them. The films were made by entrepreneurs and not studios, making them focus on the returns of their investments. The Naattukottai Chettiars were involved in the industry not for the art form but for the returns,” he added.

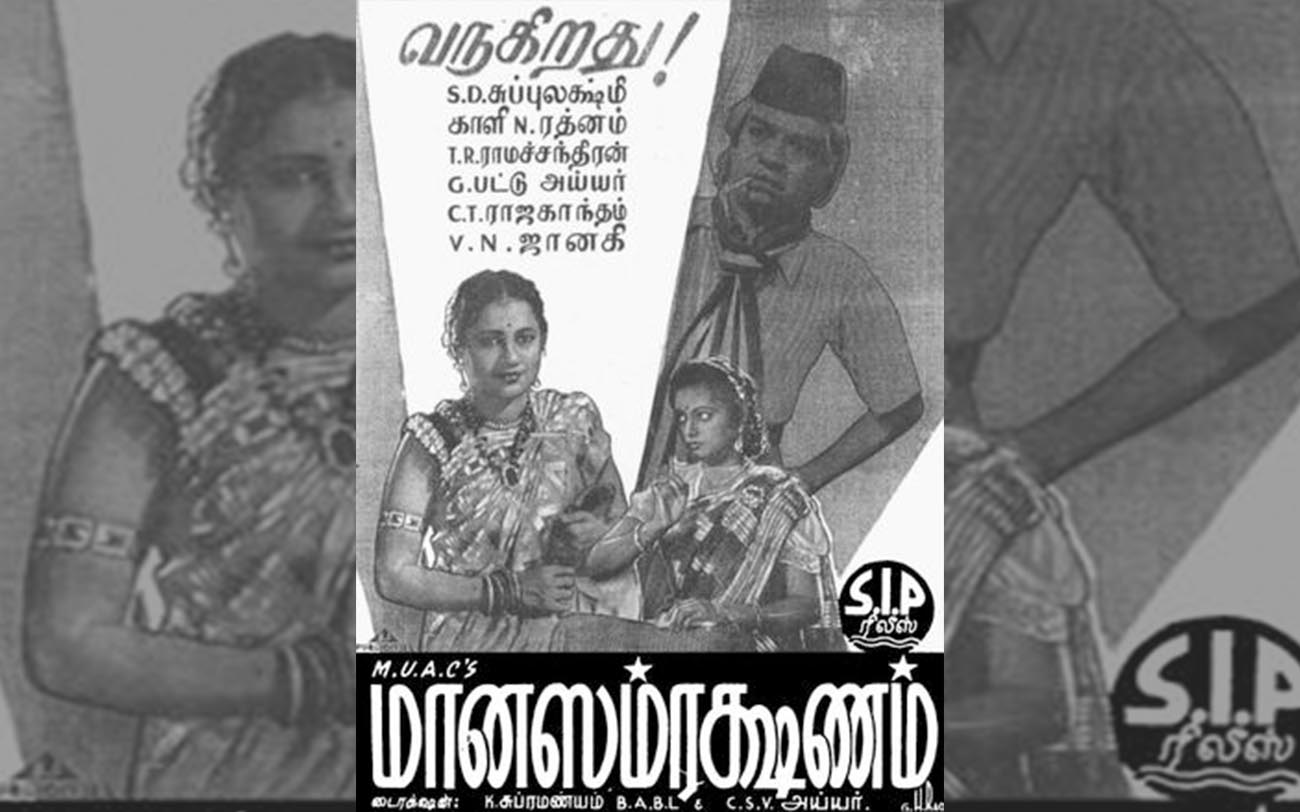

In the meanwhile, we have lost several gems that documented significant events, but were not considered of great value back then. He said, “’Manasamrakshanam’ was released in 1945 by K Subrahmanyam about the invasion of Burma by Japan, but we do not have a copy of it today, and even his family hasn’t preserved it.”

Krishnamoorthy says that filmmakers lacked motivation to preserve their work. Even though a creator assigns his/her copyrights to a publisher for commercial exploitation, under the Copyright Amendment Act 2012, it is mandatory for the publisher to come back to the creator and sign a new agreement for the commercial exploitation of the same content in a new medium.

“This additional potential for revenue generation in the future, should serve as a motivation for film preservation today, something that sadly the film makers of the 30s and 40s, never knew, as the concept of ‘storage’ and ‘private home watching’ may not have been conceivable for them, back then,” he says.

So, whatever happened to Miss Malini?

According to PK Nair, who headed the government-run NFAI and has been responsible for the preservation of several films, SS Vasan of Gemini Studios had sent a copy that the latter called ‘of not good quality’ to the NFAI, after Nair sought for it. “However, we do not know what happened to it after that. Even as Nair admitted that he received the copy in an interview in 2011, today there is no news or trace of it. “NFAI doesn’t not have an answer. The irony here is that, we are losing films sans accountability at the very same mother institution which was created for film preservation,” he pointed out.

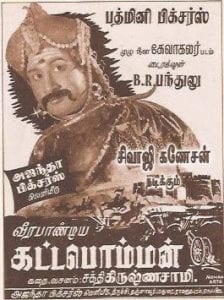

Writer-historian Venkatesh Ramakrishnan says that Miss Malini represents a time when several female oriented films were being made. “Gnana Soundari and the grandeur called Chandralekha were made at the same time. Most importantly, a lullaby in the film has the lines, ‘Gandhi mahaan, Nethaji, Kattabomman kathai koori (narrating the stories of Gandhi, Nethaji and Kattabomman) and it started a flurry of works and a film was made on Kattabomman in the next 10 years. It did for the glory of Veerapandiya Kattabomman exactly what Kalki’s Ponninyin Selvan did for the Pandavas and Pallavas.”

Writer-historian Venkatesh Ramakrishnan says that Miss Malini represents a time when several female oriented films were being made. “Gnana Soundari and the grandeur called Chandralekha were made at the same time. Most importantly, a lullaby in the film has the lines, ‘Gandhi mahaan, Nethaji, Kattabomman kathai koori (narrating the stories of Gandhi, Nethaji and Kattabomman) and it started a flurry of works and a film was made on Kattabomman in the next 10 years. It did for the glory of Veerapandiya Kattabomman exactly what Kalki’s Ponninyin Selvan did for the Pandavas and Pallavas.”

Why we will continue to lose?

However, experts also view the loss as something that will continue. Baskaran says this is because the Tamil Nadu government views as cinema as plebeian art. “We do not have a cinema department at the university as a choice of studies. Though we had chief ministers from the industry in the state, they were largely associated with the entertainment side and the criticism is always of the films made and there is hardly any focus on the medium of cinema,” he added.

Krishnamoorthy also questions the future of whatever remains. “Today, if we have to watch Pavalakkodi, one has to go to Pune and rent it at the NFAI for as much as ₹2,500. This is absurd considering that we are in the age of Amazon Prime, Netflix, and mobiles. The film along with Sati Sulochana are there in 35 mm reel form at the NFAI. They should digitize and put these films for free like archive.org or at least make it available for streaming at reasonable costs like it has been done with Sri Lankan films.

There have been no proper answers to the level of damage in 2002-03 fire at NFAI. So, applying the same logic, what if something similar happens to Pavalakkodi or Sati Sulochana?” he wonders.