On 'Dream Factories' and Booker prizes: Madhavan Narayanan on India's tryst with translations

The Indian translated literature sphere is blossoming, says the translator of one of Tamil writer Sujata's most popular works

Kanavu Thozhirsalai, a novel by Sujatha, the late popular and prolific Tamil writer, is set in the colourful Tamil film industry of the 1980s. It revolves around the lives of 24-year-old Arun Vijay, an impetuous, self-obsessed matinee idol; a poor waiter and his singular obsession to become a music composer; Premlatha, an actress who feels time is running out for her on the big screen; and Manonmani, a hapless struggling actress trying to get a foothold in the chaotic, patriarchal Tamil film industry.

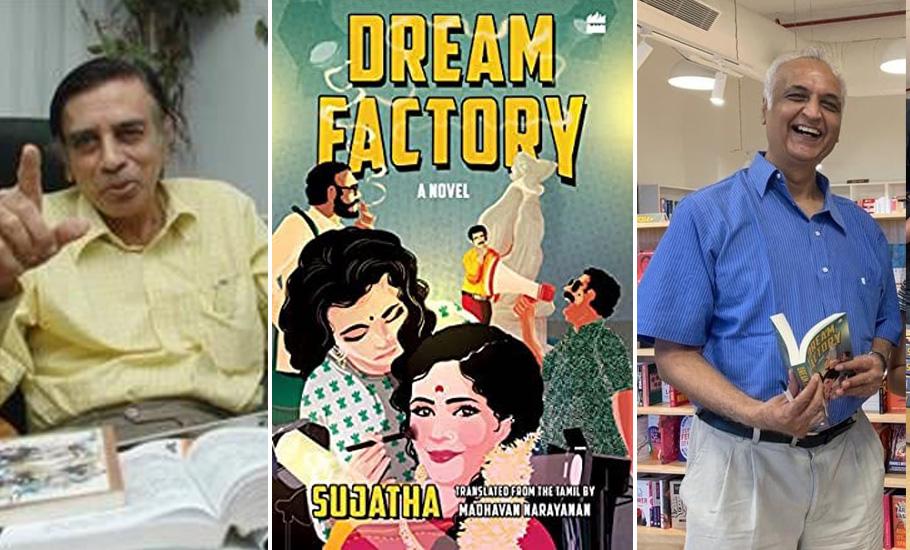

This book has now been translated into English as Dream Factory by a Delhi-based senior journalist Madhavan Narayanan. Published by HarperCollins, this racy, pulp fiction read is interestingly prefaced by an interview of Sujata by veteran actress Lakshmi and director Mahendran. Conducted after the first chapter appeared in a serialised form in Ananda Viketan magazine in 1979, they grill the author about Kanavu Thozhirsalai.

In that interview, Sujatha, whose real name was S Rangarajan (1935-2008), admits he got to interact “a lot” with the film world which obviously gave him copious material to pen this work. And, Sujata narrates how while travelling along with a film hero in his car, he saw fans crowding around the vehicle pressing their faces against the windows asking the hero to sing a song. They even slid a hand into the car to caress his cheeks and pinch it hard. This piquant incident makes its way into the book Dream Factory, with Sujata using it to show how the film hero gets angry with this invasion of his privacy.

Peek into dark side of Tamil film industry

In Dream Factory, Sujatha also gives a no-holds barred peek into the dark side of the industry through his characters whose choices lead them into ugly and uncomfortable spaces. “There is a certain poignancy in the book which attracted me,” admits Madhavan Narayanan, the translator, on why he chose to translate this particular work.

“Kanavu Thozhirsalai, besides being one of Sujatha’s best, has literary merit, a racy plot, a poignancy that I really liked. It is a rare combination of literary work and pulp fiction. It also gives insights into a disorganised film industry functioning in an ad hoc manner. It has three female characters and their exploitation in a man’s world. It is no fairy tale, but a realistic novel exposing the underbelly of a patriarchal film industry,” he says in an interview with The Federal.

To Narayanan, this translation is a way of telling the world about his favourite writer Sujatha, who is not that well known beyond Tamil Nadu. Sujatha maybe known nationally for creating the Electronic Voting Machine during his tenure at Bharat Electronics Ltd, but he enjoys a cult figure status in Tamil Nadu as a novelist. A pioneer of science fiction in Tamil, he was also a famous scriptwriter having worked on movies like Boys, Thiruda Thiruda, Roja etc. Sujatha’s sci-fi novels would imaginatively craft a Chennai post-2020, where air-taxis and gigolos reign.

According to Narayanan, whose first choice would have been to translate Sujatha’s Srirangaththu Devadhaigal (‘Goddesses of Srirangan’), on his childhood experiences in Srirangam. But, along with his publishers and agent, Narayanan decided on Kanavu Thozhirsalai, which he now believes was the right choice.

“Kanavu Thozhirsalai is an ideal way of getting a segue into the author’s works because they straddle the literary and popular very well. They have elements of visual delight, social comment and literary observations on human conditions alongside engaging plots,” he says.

Also read: Ex-Outlook Editor narrates tale of sacking in book ominous for India’s media

Sujata’s novel meets a screenplay

Sujatha seems to be taking “baby steps” towards writing screenplays when he wrote Kanavu Thozhirsalai, says Narayanan. Therefore, some of the conversations in the book seem like scenes from a screenplay. “It was like a novel meets a screenplay. I see the beginning of Sujatha as a scriptwriter in Dream Factory, his mind was already ticking, as he wrote the story in a slightly filmy style with a sense of drama, visualisation and conversation,” he asserts.

Sujatha’s descriptions of his characters tussling with their emotions, and effectively translated by Narayanan, are evocative. For example, the insecure, lonely actor Arun constantly questions the kind of meaningless films he is churning out. He mulls over his contribution in life with his secretary, his Man Friday Bhaskar, saying he feels “spread out like a shadow on a screen in the dark”.

Sujatha too nails the stereotypical characters that people the film world. There’s the banian-wholesaler-turned-celebrated filmmaker with one superhit, graduating from Berkeley cigarettes to the national brand of the film world – the 555 State Express. And, there are the vibhuti-splashed-across-their-foreheads producers committing all kinds of sins against young starlets called ‘Paapa’ and ‘Baby’.

His vivid sense of imagery pops up now and then, as he describes “the airbus jet crawled slowly like a python that had just swallowed its prey, had ladders attached to its body, opened its doors and spewed out two hundred and fifty passengers”. But, some may not take kindly to a misogynistic explanation on Arun’s height. Standing at five feet ten inches height, Sujatha wrote, Arun “could look down at his female co-stars from where he could see the parting in hair or peep into their brassieres”.

To this criticism, Narayanan says: “Sujatha took a writer’s licence to mildly titillate – he was probably influenced by popular writers of that time like James Hadley Chase, Sidney Sheldon, etc., who had bits of risqué stuff in their work. Also, we have to see the times in which he wrote. I personally feel he was self critical. Sujatha is lampooning himself when he writes about the character Arumairajan, who is obsessed with writing music lyrics. I’ve talked to Mrs Sujatha, who gave interviews after his death and one gleans that though he respected his wife a lot and even took her name, he was conscious that he was obsessed with writing. And, combined with a regular career as an engineer, he probably had no time for home. To me, he’s an extremely honest writer.”

The Kollywood hero that inspired Sujata

On the question to which Kollywood actor inspired Sujatha to frame the hero Arun Vijay’s character, an unlikely Tamil hero with a penchant for French new wave filmmaker Godard, Narayanan replies, “My gut feeling is that the character had elements of Sujatha, Kamal Hasaan and Rajnikanth. These stars were coming up in the film industry at that time and he was probably inspired by them.” It is well known that Sujata considered Kamal as a well-read man, and they were close acquaintances if not close friends.

Narayanan says, “Sujatha himself said a writer knows how to mix reality with fiction. And that clearly is his forte, to bring out reality in a fictional format.”

Also read: Rumi, Aristotle titles snapped up at Asiatic Library’s maiden book sale

Translations are the flavour of the season

Geetanjali Shree’s Tomb of Sand, translated by Daisy Rockwell, has won the International Booker Award, marking a milestone for Indian translations in the literature sphere.

On the reason why translated works from regional writers in India are the “flavour of the season”, he says: “Translated books are going through a golden age largely because there is a trend for cultural intersectionality worldwide. Also, today, there is a huge population in India that is young and literate. This generation is also not about low self-esteem, they are proud of their own culture and want to rediscover their culture. It is a journey of self discovery for Indo-Anglian kids—it also has to do with a resurgent India keen to tell the richness of Indian languages.”

Further, Narayanan adds, “Translations have been happening earlier too. Before Daisy Rockwell translated Gitajanli Shree’s Tomb of Sand, Gillian Wright did the translation of Shrilal Shukla’s Raag Darbari. We have had translated works by Sahitya Akademi; Perumal Murugan’s works; Blaft publications in Chennai published translations of pulp novels and Arunava Roy, another business journalist has emerged as a significant translator of Bengali literature. “

However, he acknowledges, the Booker Prize nomination (at the time of interview, the book had been shortlisted for the prize) is “symbolic” of the peak translations of Indian language works have touched. Incidentally, Narayanan’s book agent Kanishka Gupta from Writer’s Side is also Daisy Rockwell’s agent.

“But, in my opinion, the revolution has just begun. There’s more has to be done, works by Ashokamitran, Jeyamohan, Jayakanthan, Sivasankari and other books of Sujata’s are yet to be translated,” he says.

Challenges for translators

Last year, the late Girish Karnad’s autobiography in English, ‘This Life at Play: Memoirs’, was translated by the playwright himself (before his death) along with Srinath Perur (who so beautifully translated Vivek Shanbag’s Ghachar Ghochar as well). It was so well translated that you cannot escape Karnad’s acerbic tone throughout the book! Usually, it is a challenge for translators of Indian languages to nail the context, the setting and the voice of the original author.

For Narayanan, the biggest challenge for a translator lies in trying to nail the strong cross-cultural feel. “Some of these literary translators are obsessed with human conditions, they don’t look at the fact that language has many, many dimensions. There are slang words, aspects of the city and village you write about, cultural details from dress to mannerisms, and a good translation should be able to do all that. It needs to transport a reader who probably belongs to another culture to be able to relate to it. It is a cross-cultural experience. Translation is hugely fulfilling but demanding, and makes you restless because you are not sure if you got it right.” It is like a trapeze act with no safety net below, he says eloquently.

“I wanted to get the sights, smells and sounds of Chennai in my book. It helps that Sujatha has a god’s gift in describing scenes like the aircraft, or a character in a dubbing studio. We have included words like the Tamil tchaih (an expression of disgust or exasperation), but there was a lot of thinking that went into adding it,” explains Narayanan.

But there were some words that stumped Narayanan. In Uttarmarkovil, a small village near Trichy from which the hero hails from, kids use nonsensical words while playing hopscotch. That was simply untranslatable, he says, pointing out that it was like trying to translate Alice in Wonderland in Tamil. What he enjoyed translating the most in Dream Factory, however, was the portions set in Ramanagaram or when the author describes a film shooting taking place in a rural Karnataka setting. “I loved his descriptions of a rural milieu. It is like sitting on the banks of Cauvery or at a rural film shooting spot. There was a certain idyllic quality I enjoyed and loved.”

If a translation work like Tomb of Sand manages to win the Booker prize, it would be a wonderful way of displaying India’s soft power, reckons Narayanan. “It will herald a translation revolution as the world will discover Indian writing,” he says, adding with a chuckle that he is happy with this surge in translation of regional writers, as he gets to see his name prominently displayed alongside his favourite writer – Sujatha – on the cover of Dream Factory.