Haruki Murakami’s fictional universe is one giant fever dream

As a reader of fiction, oftentimes you yearn to travel, vicariously, to a somewhere place, a place that takes you away from the monotony of the familiar to the strangeness of the unseen and the unfamiliar. A place where the physical and the metaphysical, the mythical and the magical coalesce, unravelling worlds upon worlds. The fictional universe of Haruki Murakami, arguably the most famous Japanese Modernist writer, who turned 74 on January 12, offers that realm, at once weird and wonderful.

Murakami’s dream-like stories, forbidding yet familiar, are set in the named and unnamed mysterious alleys of urban Tokyo — invariably fraught with sociocultural displacement, disconnection and disorientation. They intersect with the axes of time and space. His archetypal characters, mostly lonesome, dissatisfied and disoriented men — normal and yet not quite normal — are as eccentric as their creator, given to myriad idiosyncrasies of his own.

The novelist, essayist and translator is seen as Japan’s next Nobel laureate in literature, after Ōe Kenzaburō (1994) and Kawabata Yasunari (1968); he is a perennial favourite of the bookies in the prelude to the announcement of the Nobel Prize for Literature every year. In a literary career spanning over four decades, he has emerged as a cultural icon, coming a long way since he made his debut on the Japanese literary firmament at the age of 30 with the publication of his laconic novel, la Kaze no uta o kike (1979), which was translated as Hear the Wind Sing.

Until then he had been running a jazz bar in downtown Tokyo, where the impulse to write a novel had struck him while he was watching a baseball game. The first of the “Trilogy of the Rat” series, Hear the Wind Sing is set in 1970 and is narrated by a 21-year-old unnamed student and bar patron, who is filled with overwhelming disenchantment towards society. He meditates on the craft of writing, relationship and loss. Like Murakami’s later novels, it’s replete with prosaic, everyday acts of cooking, eating, drinking, and listening to jazz.

Also read: ‘Novelist as a Vocation’ review: How Murakami animates the surreal world of his fiction

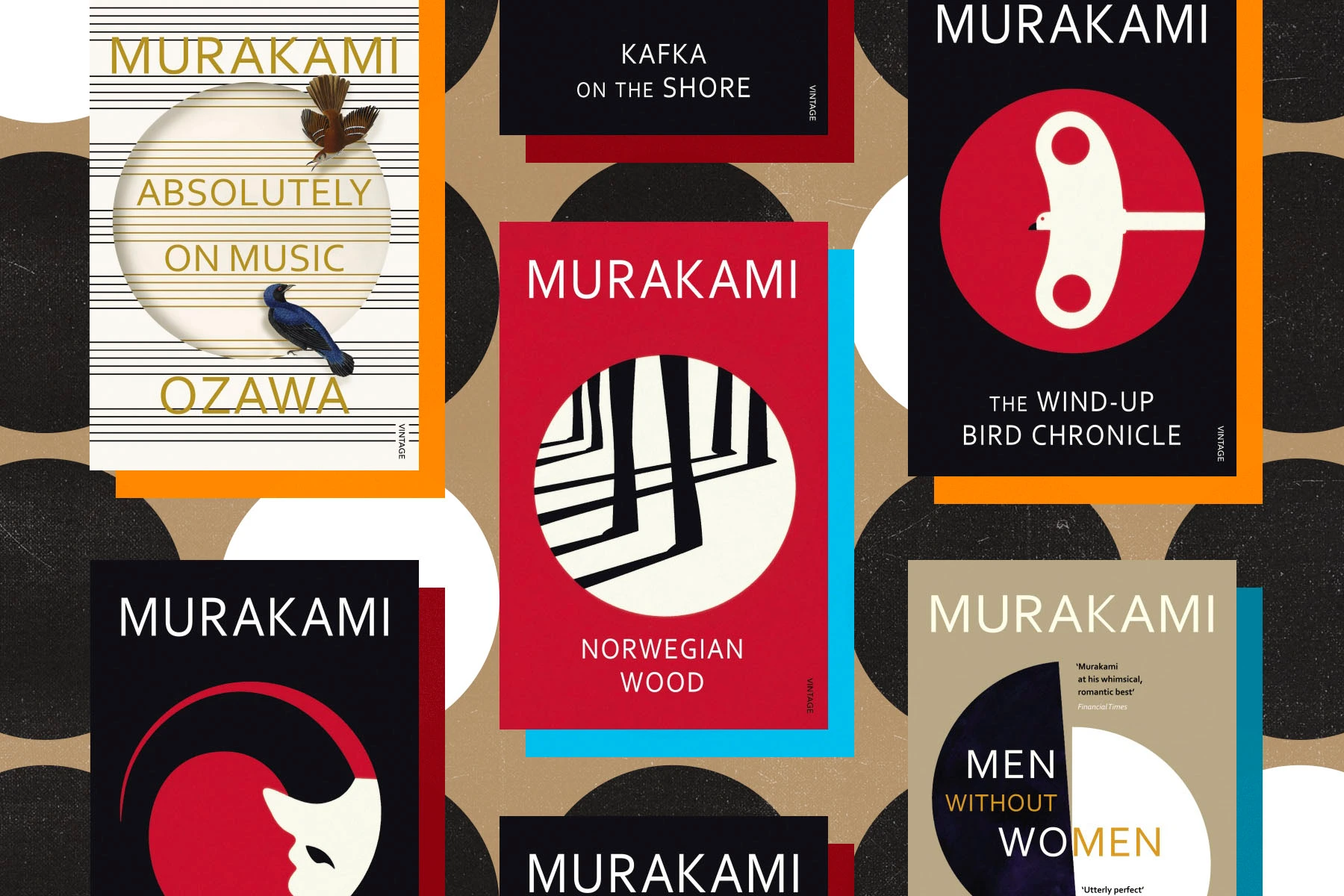

Hear the Wind Sing was followed by Pinball, 1973 (1980) and A Wild Sheep Chase (1982); Dance Dance Dance (1988) serves as the epilogue of the trilogy. Many more novels followed, including Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World (1985), but it was not until he had published Norwegian Wood (1987) that Murakami turned from a writer into a phenomenon, with massive following around the globe. His blend of the mysterious and the everyday, and humour and melancholy has cemented his place as one of the best-loved writers, who enjoys trans-national and transmedial reception; his works have been translated into more than 50 languages.

The dream-like universe

“For me, writing a novel is like having a dream. Writing a novel lets me intentionally dream while I’m still awake. I can continue yesterday’s dream today, something you can’t normally do in everyday life. It’s also a way of descending deep into my own consciousness. So while I see it as dreamlike, it’s not fantasy. For me the dreamlike is very real,” Murakami said in an interview once. It’s no wonder then that his fictional landscape is one giant fever dream, where the eerie abounds. In another interview after the publication of his latest novel, Kishidanchō goroshi (2017), which was translated into English as Killing Commendatore, he revealed: “When I write fiction, I go to weird, secret places in myself.” In Murakami’s novels, these places take the form of dimly-lit alleys, dark tunnels, pits and dungeons.

Also read: When Hanif Kureishi, who may not hold a pen again, held court in Jaipur

When Murakami started his literary journey, the initial critical reception was mixed; most established critics and writers were nonplussed. Hardly any of them expected him to last long. Many found his prose lacking in depth. With his bizarre fictional world, his rejection of belles lettres (literature as Art), his deep probing into the human psyche and his play with the metaphysical through the trope of magic realism, he upended the conventions of the prevailing literary traditions.

The odd man out

Though writers like Abe Kōbō, Nakagami Kenji and Ōe Kenzaburō had drawn on surrealism, magical realism, and the grotesque, most readers and writers in post-war Japan believed in literary works with serious social, political or philosophical agenda; in short, they believed in creating literary Art for its own sake. Looking back on those days, Murakami admitted in a 2005 interview: “I was kind of an odd man out compared with other writers, and was almost totally shut out by the Bundan [literary guild] system in Japan. . . . The world of literary arts saw no value in me, and disliked me. . . . They said I would destroy the traditions of Japanese literature.”

Also read: Inside the violent, visceral world of Cormac McCarthy, one of America’s greatest writers

The enfant terrible of contemporary Japanese literature, Murakami doesn’t fit any pattern or follows any formula; he does not play the Japanese game by Japanese rules. If the critics saw little merit in him in his initial years, he has given them back in the same currency as Japan’s most recognised writer: he refuses to be a part of the Japanese literary establishment, the jun bungaku (“pure literature”) crowd that makes up the Bundan, which has lost the influence it once used to wield.

Having struck his own path, Murakami continues to live and write the way he wants, acutely aware of his position as a global writer whose conscience is clean. In 2019, when he went to Jerusalem to accept the Jerusalem Prize from the Israeli government, he did not refrain from criticising Israel for its military actions against civilians in Gaza. His message was clear: If Israel chose to bring its massive military and political power against the individuals protesting in the Gaza Strip, he would stand firmly against the government. Using the “wall and eggs” metaphor, he declared that the powerful political systems could be seen as the great stone wall, and individuals as eggs, hopelessly hurling themselves against its implacable might.

“Each of us is, more or less, an egg. Each of us is a unique, irreplaceable soul enclosed in a fragile shell. This is true of me, and it is true of each of you. And each of us, to a greater or lesser degree, is confronting a high, solid wall. The wall has a name: It is The System. The System is supposed to protect us, but sometimes it takes on a life of its own, and then it begins to kill us and causes us to kill others — coldly, efficiently, systematically. . . . Between a high, solid wall and an egg that breaks against it, I will always stand on the side of the egg,” Murakami said in his acceptance speech in Jerusalem.