JCB Prize for Literature: In a first, five translated works on the shortlist

It’s a record of sorts. All the novels on the shortlist of the 2022 JCB Prize for Literature, which were announced at the Glenburn Penthouse in Kolkata on Friday, are translations from South Asian languages: Urdu, Hindi, Bangla, Malayalam, and Nepali. This is unprecedented in the five-year-long history of the Rs 25 lakh Prize, which will be announced on November 19; even though it has awarded more works in translation than books originally written in English so far. The last two winners were books in Malayalam: S. Hareesh’s Moustache (translated by Jayasree Kalathil) and M. Mukundan’s Delhi: A Soliloquy (translated by Fathima EV and Nandakumar K).

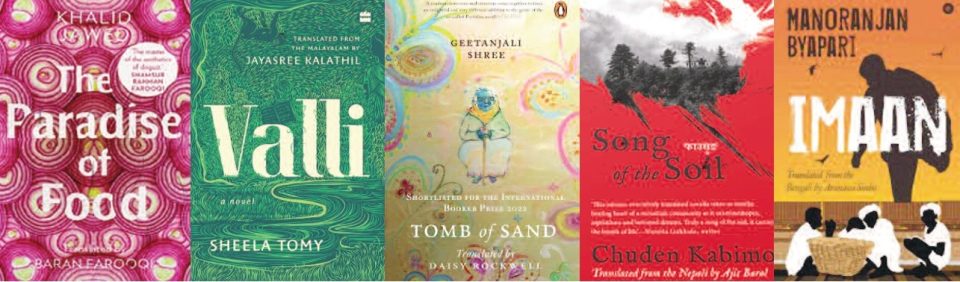

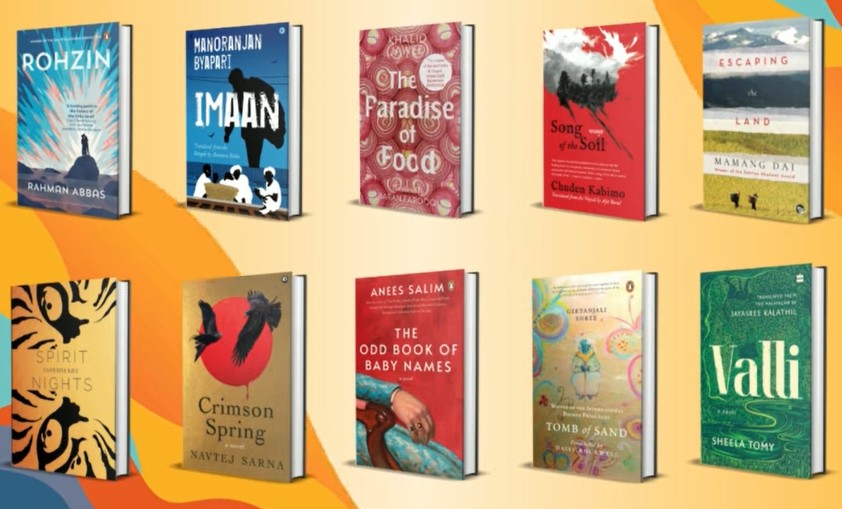

The winner of the inaugural Prize, which was started in 2018, too, was a Malayalam-language author: Benyamin for Jasmine Days (translated by Shahnaz Habib). Only one English-language has so far won the award: Debutante writer Madhuri Vijay for The Far Field in 2019. In this year’s race, there are two translators and an author vying for the award for a second time: Kalathil for Valli: A Novel by Sheela Tomy (Malayalam, HarperCollins India) and Arunava Sinha, who was shortlisted for Manoranjan Byapari’s There’s Gunpowder in the Air (Bengali) for the latter’s another title, Imaan, published by Eka (Westland).

The Longlist: Stories that surprise and delight

The longlist of 10 books was announced on September 3: it comprised six translation titles, along with four books written in English: Anees Salim’s The Odd Books of Baby Names (Penguin Random House), Navtej Sarna’s Crimson Spring: A Novel (Aleph Book Company), Mamang Dai’s Escaping the Land (Speaking Tiger), and Eastern Kire’s Spirit Nights (Simon & Schuster). For the first time, two Urdu novels made the cut, whittled down from scores of books from 16 states in 8 languages that entered for the Prize this year: Rohzin by Rahman Abbas (translated by Sabika Abbas, Penguin) and The Paradise of Food by Khalid Jawed (translated by Baran Farooqi; Juggernaut).

“All the longlisted books have a common denominator — a rich and varied story, and language that surprises and delights. By creating new and engrossing realities they took us back to when we were younger and just discovering the world,” said Mita Kapur, Literary Director of the JCB Prize for Literature, when the longlist was announced.

Also read: Sri Lankan author Shehan Karunatilaka wins Booker Prize

The shortlist: A representative of the many Indias across time and geography

Announcing the shortlist on Friday, Kapur said: “The list brings forth the many Indias across time and geography, [and is] representative of the spectrum of languages… that India has to offer.”

Commenting on the shortlist, the chair of jury 2022, AS Panneerselvan said, “Judging literature is a challenge. From exploring new content and deploying various literary devices, authors constantly try to push the boundary. Every step is crucial and every innovation is precious. However, when the final evaluation happened, these wonders of the mind gave space to the power of the heart, where empathy became the criteria for creating the shortlist. All the novels in the shortlist exemplify the idea of empathy, concern for fellow humans, and in a sense a worldview in which the head does not subsume the heart.”

Baran Farooqi, a professor of English at Jamia Millia Islamia, who is on the shortlist, told The Federal: “The shortlist for the JCB Prize this time is a landmark in itself for this has shown that translations are what the world is looking out to read, they are the way to go. Why? Because fiction in the languages of India is a fiction worth reading, and it is writing in the language of one’s own culture and region that has the potential to deliver. I’m delighted that the translation of an Urdu contemporary novel has gone down so well with the jury, with the showcasing of Khalid Jawed’s writing, an immense hope has built up in me for Urdu fiction getting a more vigorous and visible lease of life.”

The two other books on the shortlist are Tomb of Sand by Geetanjali Shree translated from Hindi by Daisy Rockwell (Penguin Random House India), which won the International Booker Prize this year, and Song of the Soil by Chuden Kabimo Lepcha, translated from Nepali by Ajit Baral (Rachna Books).

The Paradise of Food: An account of body, home and nation

Translated from Jawed’s Urdu novel, Nemat Khana, The Paradise of Food tells the story of a middle-class Muslim joint family over a span of fifty years. As India – and Islamic culture – hardens, the narrator, whose life we follow from boyhood to old age, struggles to find a place for himself, at odds in his home and in the world outside.

But to describe the novel in its plot is to do its originality no justice. In this profoundly daring work – tense, mysterious, even unfathomable on occasion – Jawed builds an atmosphere of gloom and grotesqueness to draw out his themes. And in doing so he penetrates deep into the dark heart of middle-class Muslims today.

The Jury says: “It is a brutal and mesmerizing account of the contemporary body, home and nation told through the food and kitchen. In a world consumed by hyper-consumerism, the book provides a bracing counter-narrative making it an important piece of work. The incredibly skillful translation highlights the poetry and music of the original text.”

Also read: Annie Ernaux is an ethnographer of memories, a master of autofiction

Valli: Stories of the land and its people

Spanning the time between the 1970s and the present, Valli is a tale of four generations who made Wayanad in Kerala their home. It is told through a diary that Susan – the daughter of two teachers, Thommichan and Sara, who eloped to Wayanad so that they could live together – leaves for her own daughter, Tessa.

And in telling their story, Valli tells us stories of the land and its people, of interdependence and abuse, repression and resistance, despair and contentment — stories as vast and magical as the forest itself once was.

The Jury says: “Valli is a beautifully written work that transports us into another time and place. It presents a world gone by in which the natural world is an extension of the human world. The prose has many textures, with letters and quotes from scriptures, making for deeply satisfying reading.”

Tomb of Sand: Transcending barriers

In northern India, an eighty-year-old woman slips into a deep depression after the death of her husband, and then resurfaces to gain a new lease on life. Her determination to fly in the face of convention – including striking up a friendship with a transgender person – confuses her bohemian daughter, who is used to thinking of herself as the more ‘modern’ of the two. To her family’s consternation, Ma insists on travelling to Pakistan, simultaneously confronting the unresolved trauma of her teenage experiences of Partition, and re-evaluating what it means to be a mother, a daughter, a woman, a feminist.

Rather than respond to tragedy with seriousness, Geetanjali Shree’s playful tone and exuberant wordplay results in a book that is engaging, funny, and utterly original, at the same time as being an urgent and timely protest against the destructive impact of borders and boundaries, whether between religions, countries, or genders.

The Jury says: “Wild and unruly, Tomb of Sand challenges our notions of what a novel should be. The impression of several novels within one give it a carnivalesque atmosphere. This novel is witty and irreverent yet filled with tenderness and psychological insight.”

Song of the Soil: The story of the revolution

Set in the foothill town of Kalimpong in the Himalaya, Song of the Soil brings alive the story of the revolution for a separate state of Gorkhaland in the late 1980s. Clear-sightedly, it lays bare the many faces of violence. And in doing so, it asks the vital question: Who, ultimately, wins in a revolution—and who loses?

Also read: French novelist Annie Ernaux wins the 2022 Nobel Prize for Literature

On a day of earthquake and rain, a young man gets bad news. Ripden, his childhood friend, has been swept away by a landslide. So he makes his way back to Malbung, the village of his birth. The memories come rushing back. Of growing up together; the harsh teachers at school and playing truant; bullies and backyard fights. Nasim narrates to them an extraordinary tale from his younger days. Of himself and other child soldiers of the revolution; building pipe guns and homemade bombs; fighting pitched battles with the police; training in jungle camps and enduring drink-fuelled night time raids; witnessing a massacre in the town square; and suffering a final, unforgivable betrayal.

The Jury says: “Song of the Soil is a shining example of how one can write about a violent incident without recreating the violence. The author blends bildungsroman with a conflict story with great dexterity, bringing out new aspects of both forms. This book is able to make poetry out of brutal situations but does so with honesty, humour, and gentleness.

Imaan: A searing examination of the faceless

Written in Manoranjan Byapari’s inimitable style, where irony and wry humour are never too far from bitter truths, this new novel is a searing exploration of the lives of the faceless millions who get by in our towns and cities, making it through one day at a time.

Imaan entered Central Jail as an infant—in the arms of Zahura Bibi, his mother, who was charged with the murder of his father and who died when he was six. He left twenty years later, having spent his time thus far shuttling between a juvenile home and prison. With no home to return to, Imaan ends up at the Jadavpur railway station, becoming a ragpicker on the advice of a consummate pickpocket. The folk of the railside—rickshaw-pullers, scrap dealers, tea-stall owners, those who sell corpses for a little bit of money—welcome him into their fold, but the world of the free still baffles him.

Life on the platform is disillusioning and far more frightening than the jail he knew so well. This free world too is a prison, like the one he came from, only disconcertingly large. But no one went hungry in jail. And everyone had a roof over their heads. Unable to cope in this odd world, Imaan wishes to return to the security of a prison cell. He is told that, while there is only one door out of prison, there are a thousand through which to return. Imaan—whose name means honesty, conscience—is he up to the task?

The Jury says: “Imaan is a completely novel iteration of the humanist tradition of Bengali literature. It presents a vivid portrait of people from the periphery but is neither voyeuristic nor patronising. Each character has agency no matter how circumscribed their life may be. A raw, deeply authentic and honest story which is also well-paced, poignant and eloquent.”