Three reasons behind India’s wheat shortage, and ways to avert future crises

Sweltering heat, the Ukraine war and loopholes in supply-demand management are some of the factors for the sudden crisis India finds itself in

Intense heatwave, the Russia-Ukraine war and loopholes in supply-demand management are some of the factors that have resulted in wheat crisis in India in particular and the world in general.

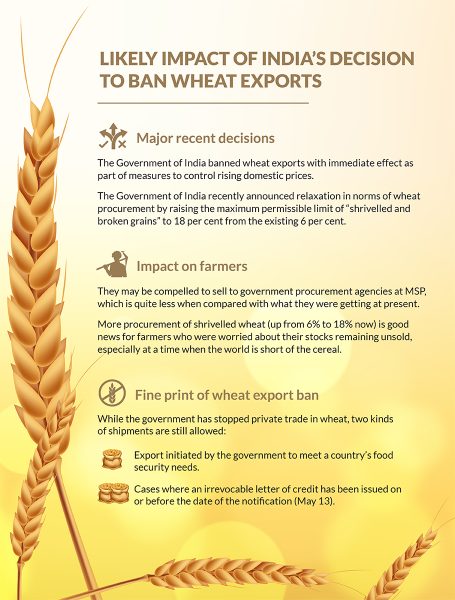

The problem was compounded after the Centre’s sudden decision to ban wheat exports last week, just days after saying it was targeting record shipments this year. India has already exported 7 million metric tonnes (mmt) of wheat in 2021-22 and looked all set to hit a record export of 10 mmt. However, domestic price pressures and rising food inflation compelled the government to curtail exports.

India, though the second largest wheat producer in the world after China, is not even considered a major wheat exporter. So, when India’s sudden decision to ban wheat exports shook the world, analysts viewed this as an unprecedented food crisis unfolding in the backdrop of extreme wheat shortage.

Heatwave played spoilsport

The Centre’s emphasis on promoting wheat export throughout April and early May was based on estimated production of 111.32 mmt of wheat this time. But excess heat between February and March this year dealt a big blow to its plans. As per private assessments, the crop yield could be less than 100 mmt, which is likely to have changed government projections.

Dealers say that government procurement is down by about 50% and spot markets are struggling to get supplies. This is essentially because of lower production, which can be attributed to the heat factor.

Desperate to control domestic food inflation, the Centre on Sunday (May 15) declared significant relaxation in the Fair and Average Quality (FAQ) norms of wheat by raising the maximum permissible limit of “shrivelled and broken grains” to 18 per cent from the existing 6 per cent.

Lessons from the 2006 crisis

The temperatures went soaring in the north-west regions of the country during February-March in the year 2006. The Agriculture Ministry then could not estimate the upcoming crisis, but the traders did. The government estimated production of 75 mmt but the actual production fell by 10%, compelling India to import wheat, a practice which had almost stopped after the successful launch of the Green Revolution in the 1960s. The traders smartly sensed the crisis that was unfolding by buying at higher than minimum support price (MSP) and later making big profits as the market demand soared.

Podcast: ‘Govt shifting burden onto farmers with wheat export ban’

The situation this time is no different. The Centre has estimated wheat production at 111 mmt, but the prevailing heatwave could result in approx. 15% drop in production. In a repeat of 2006, traders have become active, buying at higher than MSP. The government is unable to stock enough wheat at MSP because the market is offering a higher price.

All these factors worried the government which hit the panic button by banning exports, resulting in a loss of opportunity for farmers to make profits even as the world wheat prices go through the roof mainly because of short supply from Russia-Ukraine — the two countries account for 50 mmt of wheat exports in the global export market of 190 mmt.

Ban on exports could be a knee-jerk reaction, which could have been avoided. As on April 1, India had wheat stock of 19 mmt — a number significantly higher than the buffer stock requirement of 7.4 mmt. In comparison, the country has sufficient rice stocks (57.2 mmt). Despite allocations to various government welfare schemes for the poor and needy, this year’s requirement would be about 20.5 mmt while the country requires 82 mmt under public distribution system (PDS) and other schemes for the year 2022-23. For 2023-24, the requirement is likely to go down to 62 mmt. So even if wheat purchase by the government is lower this time, say up to 20 mmt, we have enough reserves of rice and wheat for the year. What is required is efficient resource allocation and smart supply-demand management.

It makes sense to extend the export window further because despite less production of wheat this year, the stocks with farmers and private traders is high enough to sustain at least for a year.

What should the government do?

As wheat production dips, the Centre could reduce procurement and encourage open market sales to cut prices, thus helping keep food inflation in control.

By giving a free hand to the private sector to export, and not releasing buffer stocks from the Food Corporation of India (FCI) godowns, the government can help Indian farmers realise higher price and the world meet its wheat deficit. Such a move will be in sync with India’s commitments to the World Trade Organisations (WTO)— especially the ‘peace clause’ of the Bali ministerial agreement.

Also read: Fortified rice is nice, but the Centre’s plan to promote it is flawed

In a way the Centre can release more wheat stocks for the open market. Additionally, it should divert its attention to rice, which is held in the buffer stocks in excess. Distributing rice through PDS can easily compensate for the shortfall of wheat.

The government should also promote coarse grains like jowar, bajra, kodo, raagi and other millets in mid-day meals or government welfare programmes because of their high nutrition value.

The government will do well by keeping a close eye on private stocks. Depending on the situation, anonymised stock reporting (over 1,000 tons) should be made compulsory along with efficient supply and demand management.