Sino-India war 1962: What exactly caused Delhi's intelligence failure

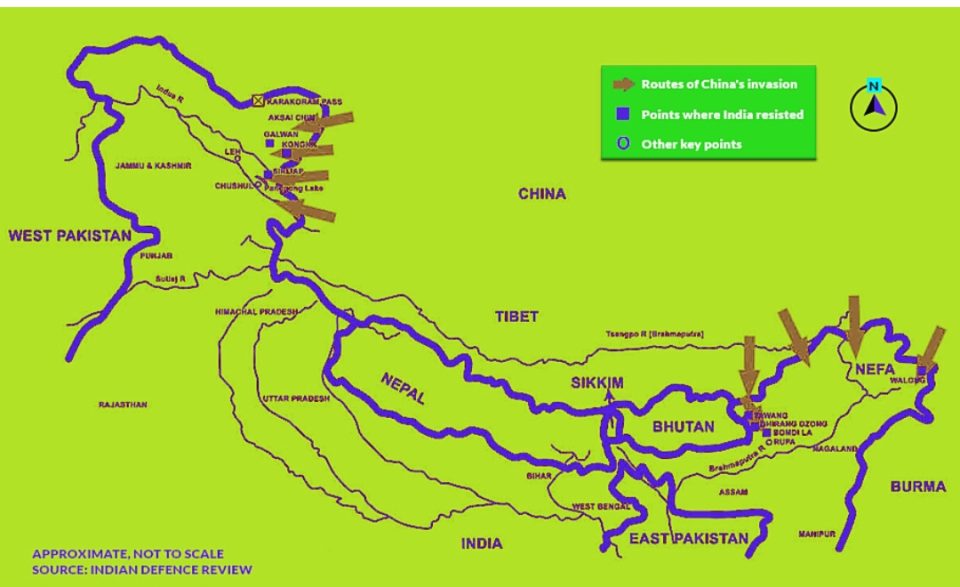

A look back at the war 60 years later suggests that while Indian intelligence assessed Chinese military capabilities accurately, it overlooked Beijing’s political-military intentions; the data was meticulously collected, but not adequately analysed

Looking back 60 years later, one key intelligence lesson that the 1962 India-China war teaches us is that collection capabilities – human, technical, and international intelligence cooperation – are vital for measuring an enemy’s capabilities. However, analytical capabilities built in peacetime are critical to develop an accurate estimation of the enemy’s intentions.

The Indian intelligence failure was that while the Intelligence Bureau (IB) assessed Chinese military capabilities correctly, it overlooked Beijing’s political-military intentions.

Nascent days of cross-border espionage

Prior to 1952, foreign intelligence in India was almost entirely the responsibility of the diplomats. In 1950, the Indian diplomat in Beijing failed to provide any warning of China’s plans to annex Tibet.

Following the annexation, the IB had produced a note titled “New Problems of Internal Security,” forecasting a potential nexus between Maoist China and communist insurgencies in India, which also became the basis for then Home Minister Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel’s famous letter to then Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, suggesting an alteration in India’s diplomatic relations with China.

Owing to these considerations, strategic intelligence – military, foreign (political and economic), besides internal – was entrusted to the IB. However, improvements in intelligence collection capabilities were only gradual.

Also read: India-China tension spikes as Dalai Lama reaches Ladakh

Between 1951 and 1962, the IB raised the number of border posts from 30 to 77. But these posts suffered from severe resource constraints and were merely symbolic and bereft of capabilities. Also, human intelligence coverage in the eastern sector favoured the Chinese over Indians. The Chinese in Tibet had their trained operatives to masquerade as pseudo-traders and imparted language skills in Hindi, Nepali and Bengali.

It was only closer to the war that the IB could develop a similar human intelligence network inside Tibet. This allowed the IB to monitor troop movements accurately, but strategic intentions could not be deduced due to lack of sources in Beijing. Thus, based on a source in Tibet, the IB could report on June 8, 1962 that an attack was imminent but got other finer aspects of China’s intentions wrong.

IB fell short of specialised knowledge

Despite the warning, the IB prescribed the “Forward Policy” (deployment of military presence until the Indian claim line), reflecting weak analysis. The agency had relied on observing past actions of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) on the borders to draw strategic estimates. Wherever there was an Indian post already set up within India’s claimed line, the PLA was observed to not attack despite numerical superiority. This pattern was projected by the IB into the future as well.

It is possible that the IB’s commitment to its analysis was strengthened by the Central Intelligence Agency’s (CIA) sharing an order from the PLA regional headquarters in Tibet, directing its border troops not to clash with the Indian troops, whatever the level of provocation.

Encouraged by this input, the IB projected previous behaviour patterns to the future. An offensive to capture territory was never hypothesised. This directly related to the IB’s complete lack of military knowledge. Reflecting the state of military analytical capability within the IB, an officer of the era regarded it “rudimentary and semi-amateurish” while another called the IB’s military analysts “clueless jokers”.

Therefore, even as collection capabilities improved and the IB’s monitoring of the PLA’s capabilities was accurate, estimation of China’s intentions required specialised knowledge, which the agency fell short of.

Blunder of mirror imaging

The second analytical blunder the IB committed was to project one’s own behaviour on others, also known as mirror-imaging. Although the IB’s top leadership were experts in international communism and its expansionist tendencies, understanding of Maoist China was limited. For instance, N Narasimhan, a former China analyst at the IB, recollected how much of their time was spent reading Chinese propaganda. An objective study of Mao would have shown significant cultural differences.

Prior to the war, there were strong voices in both countries calling for military action, while economic problems worsened on either side. The IB underplayed the influence of those opinions on China’s foreign policy and regarded economic challenges as a deterrent against military action.

By doing so, the IB analysts were only projecting what they would have done in such a situation. Immersed in a democratic culture, the idea of an authoritarian like Mao using war as a diversion from internal troubles did not occur to the IB.

Language hiccups

Similar to the lack of area and military specialisation was the state of language skills. Despite the obvious weaknesses in decryption technology, the real issue was that there were only half-a-dozen Chinese speakers in India to interpret the intercepted communications. A notification put out by the Federal Public Service Commission (FPSC) seeking Chinese language trainers for the Armed Forces Academy had no takers while ad-hoc measures were taken by the IB to train its analysts in foreign languages.

The IB then began to rely on the US and the UK to fill vital gaps in its strategic assessments. However, two principal reasons caused hiccups in relying on the western agencies for analysis. First was the suspicion among the western agencies regarding information security in India, owing to the appointment of Krishna Menon as Defence Minister.

There were suspicions in Washington that Menon was a Soviet agent and had directed London also to restrict sharing of intelligence with India. It was only after Menon was deposed that the British Joint Intelligence Committee (JIC) assessed that the information security situation in India had improved, and that Washington also would be willing to share intelligence with India.

Also read: Five in 4 months: China blocks India-US bid to sanction another LeT terrorist

The second major challenge in liaising with the western agencies was the nature of analysis itself. Not sharing borders with China, the priorities of the western intelligence agencies were different from that of India. Therefore, while the western agencies saw it fit to share pieces of intelligence, they were always sanitised according to their perception of India’s interests.

Therefore, as memories of the 1962 war continue to invoke intelligence failure as a causality, deeper analysis suggests that there were both failures of collection and analysis. Essentially analytical failures exacerbated the impact of collection weaknesses.

(The writer is the author of ‘India’s Intelligence Culture and Strategic Surprises: Spying for South Block’)