Asterix and the generation gap

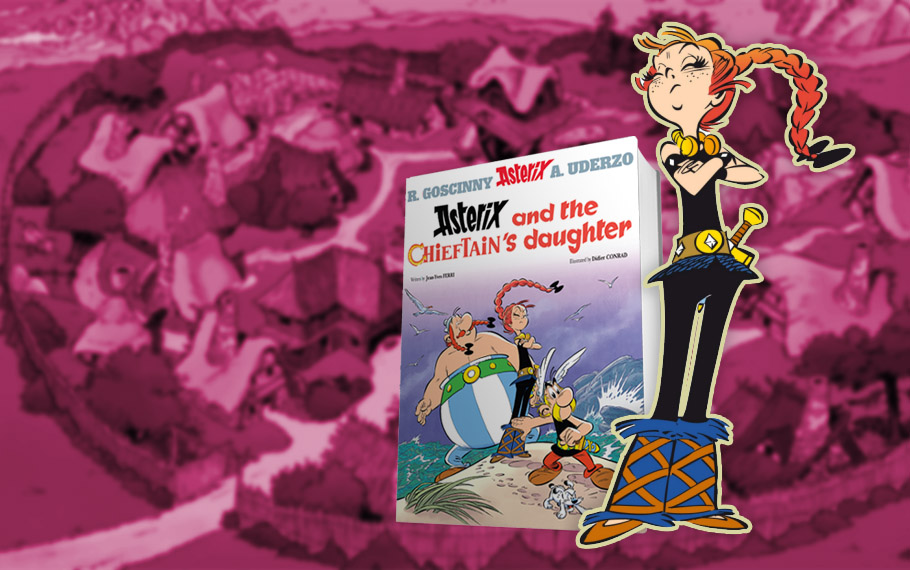

The newest Astérix album came out on October 24, 2019. This 38th title seems all set to

introduce even more upheavals in the world of the Gauls.

Stable for close to 50 years, the series underwent a number of significant changes over the past few years. In 2013, Astérix chez les Pictes (Asterix and the Picts) became the first-ever Asterix and Obelix album that had neither Goscinny nor Uderzo’s name on the cover. Instead, Uderzo (Goscinny died in 1977) authorised a new duo to take up the baton, following his own health problems that made drawing difficult. Thus, the writer Jean-Yves Ferri and the artist Didier Conrad (whose work Uderzo closely tracks) came in.

In 2017, Asterix and the Race through Italy (French: Astérix et la Transitalique) was the first Astérix album in English not to be translated by Anthea Bell, who had worked on the series until she retired in 2016. Adriana Hunter took up the translator’s pen, both excited and apprehensive about filling Anthea Bell’s shoes. While the 2017 comic itself was not a great success, Hunter’s translation proves that the spirit of Anthea Bell and Derek Hockeridge’s translations live on. And all books still end with the familiar banquet, without which, it is certain, none of us would really believe the story was over.

This newest title seems to be in line with the constant theme of change – it is a book that focuses a great deal on the next generation, something that the titles have so far not done. The village is protecting and babysitting the daughter of a famous chieftain (Vercingétorix, of course, the real-life historical figure who defied Caesar and inspired Uderzo and Goscinny to create the suffix ‘ix/-rix’ for all their characters).

The girl and her friends are typical adolescents, questioning and challenging established practices (including the magic potion! As a blasé young boy asks, “Who knows what goes into that?”) and promoting peace and challenging unfair or problematic practices. While the early reviews suggest that the story promises an interesting inter-generational conflict without fully exploring it or delivering, it still lands several punches. Alas, for all those who read or believed that Adrenaline (the young heroine) was based on Greta Thunberg, the creators have dismissed the rumours stating that there are certain characteristics in common, certainly, but these are in retrospect, given that they created Adrenaline two years ago and she’s based instead on their own daughters.

Even as we gear up, then, to explore the fascinating world of Asterix no. 38, let us pause a bit and look back over its history, to see how this series it made its way out of France and into our lives and interests – and possible reasons it continues to flourish.

A British translator, Anthea Bell, was first approached by a publishing firm to translate the comics in the 1960s, about 10 years after they released. This task had seemed rather daunting to the literary world until then. She was paired with Derek Hockeridge, a professor of French who was able to help her navigate the various cultural and social references in the books.

Bell’s approach to translation, which she has stated in many different places, was to offer the readers a text that they read absolutely fluently, without it registering that it’s a translation. The creative and fabulous translations she used, especially with respect to the names of various characters are excellent examples of what she meant. While she often went beyond the original text, she also ran her translations past Réné Goscinny, who spoke fluent English, to ensure that she was not violating the spirit of the original. Almost all English readers of the series who fell in love with them fell in love as much with Anthea Bell’s clever puns and deft wordplay as they did with the original stories and dialogues (through her translations).

Bell named over 400 characters, sometimes translating the concept from the French (like the beautiful ‘Dogmatix’, working off the English word ‘Dogma’; the French name is idéefix meaning ‘fixed idea/obsession’) or just inventing new words that seemed appropriate to the occasion/function.

One of the examples she herself often cited, of going beyond the text and creating her own name, was that of ‘Getafix’. While the French name for the Druid (Panoramix) would have worked in English, the instant associations English speakers would make with ‘Get a fix’ (mixing up things, a chemist, obtaining a cure/drug) were perfect for the functions the Druid performed.

These translations introduced Astérix to various corners of the Anglophone world, including to India, where the series has a strong and passionate fan base. Further, not only are they available in English, but they have also more recently been translated into various Indian languages, which brings with it its own challenges and rewards.

Translating comics is a significant double-challenge: not only must one translate puns and pithy, punchy phrases, the translations must also match the length of the original because they have to fit in the same speech bubble or text-box. This is much harder when the script of the translated language is itself different from the original.

The Hindi translators of the series (working directly from French into Hindi) have often spoken about the difficulty in fitting the Devanagari script with its diacritics or maatras (the marks that indicate the ‘ee’ and ‘oo’ sounds as well as the addition of the symbols that add a nasal sound). But these very restrictions often force translators to arrive at creative solutions they might never have thought of if they had had a wider field.

[One of my personal favourites is the Hindi translation for the character known in English as Cacafonix: ‘Besuratalix’. This is a brilliant rendition of his key characteristics in very idiomatic usage (a direct translation of this into Tamil could be ‘Abaswaratalix’)]

Given the number of countries the books spread to (various titles translated into over 80 languages) what is it about these stories that resonate so strongly across cultures, languages and time-periods? (Remember – the first book came out in the 1950s)

Is it the universal sentiments of friendship, resistance, fighting against injustice, adventure and travel (Asterix and Obelix travel to many parts of the world in their different adventures), satire and gentle mockery of stereotypes, as well as the groan-worthy bad puns and the undeniable fact that good food and drink abound through the pages?

More relevant in today’s time perhaps: the Gauls symbolise a resistance to tyrants who surround them (or other allies) with armed forces, always outwitting and thwarting these destructive, occupying forces. Secondly, their village is cheerfully chaotic, with dysfunctional yet closely-knit residents. They may go hammer and tongs at each other, but they form a solid, united phalanx in the face of opposition. And at the end of the day, they all gather around the same table and share food and drink and general happiness. It would be nice, in today’s India, to believe that we see in these characteristics, resistance and the love of harmony and community, the values that Indians proclaim to treasure and that we may one day truly display.

(The writer is a freelance translator who holds master’s degrees in Translation Studies from Durham University, UK, and in Psychology from Madras University, Chennai.)