Tracing stolen idols: An 'archival' method

For decades, the French Institute of Pondicherry has been archiving photographs and documents on Tamil Nadu temple art and idols. Now, this is helping retrieve stolen idols, which were largely neglected.

N Vinoth Kumar

06 March, 2020

"What are you going to do with this masterpiece?" asked Phylarkkas.

"What question is this? I am going to dedicate it to the temple in the King's palace," Saathan responded.

"What nonsense," hits back Phylarkkas, and suggests that it was so beautiful that it would be appreciated whether it was placed in a king’s harem or broken into pieces and thrown over a mountain.

This is a scene from the short story Sirpiyin Naragam (The Sculptor's Hell) written by Pudumaippittan, who is considered a pioneer of modern short story in Tamil. First published in the magazine Manikodi on August 25, 1935, the story is set in Kaveripoompattinam, an erstwhile port city in Tamil Nadu in the 11th century CE and revolves around Saathan, a sculptor who has just completed a life-sized Nataraja idol.

Phylarkkas, a Greek who was in town for business, had come to know Saathan through an unnamed Hindu hermit, who was a common friend. And Phylarkkas, on seeing the beautiful idol, is unhappy that Saathan is planning to dedicate it to the temple. He says that if the idol is kept inside the sanctum sanctorum of a temple in darkness, no one is going to appreciate its beauty.

However, the hermit views the Nataraja idol as an answer by Hinduism to defy Jainism which was growing fast at that time in the state.

According to author Gopinath Sricandane, this short story brings out the conflicting viewpoints of temple art. It also essentially captures how a beautiful idol, though a work of art, gains the quality of worship potential, even with the passage of time and irrespective of where it is kept, including inside a dilapidated temple.

This antiquity is highly valued by all, and is especially appreciated by collectors and idol thieves across the world.

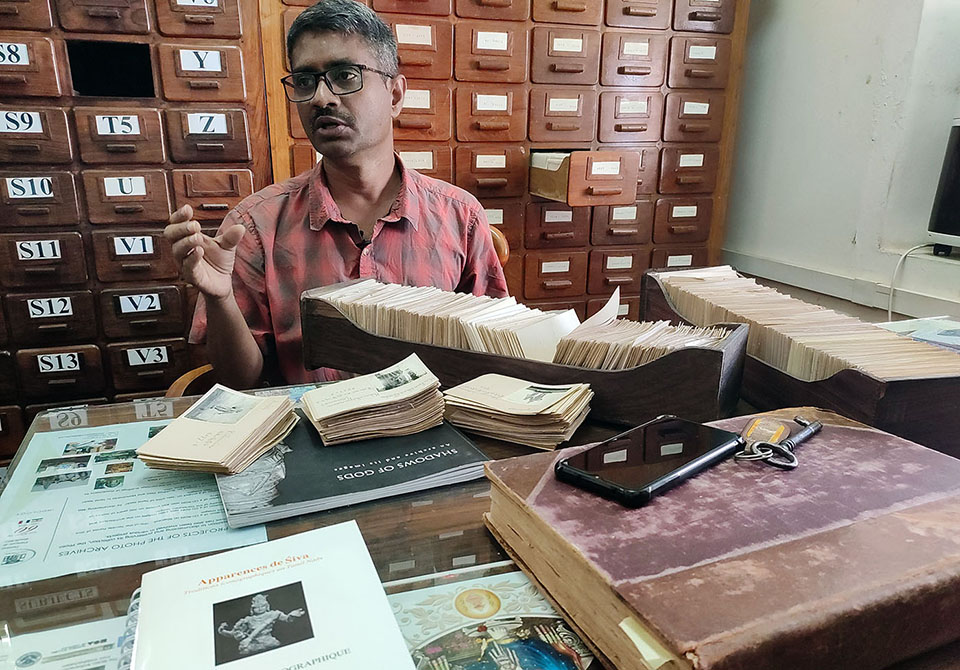

K Ramesh Kumar, photographer-turned-archivist, French Institute of Pondicherry, notes that each and every information of an idol has its antique value.

"The shape, the material used, the period it was made and the name of the idol, (everything) has its own value. The value of an idol increases according to its antiquity," he says.

History of idol care

There is an adage in Tamil that says 'Don't live in a village, where there is no temple'. People of ancient Tamil Nadu lived up to this maxim so much, that they built as many temples as possible, big and small, across the state. The triumvirate dynasty — Chera, Chola, and Pandya — built many temples using traditional knowledge and any material that they laid their hands on. As a result, the state has more than 44,000 temples, which are managed by Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowments (HR & CE) department of the state government.

In ancient times, when kings raided rival kingdoms, they used to steal idols after demolishing temples there. Since the 17th century, when the British entered India, idol theft became rampant and the British used to take them to the UK, legally.

Post-Independence, when the nation was busy reconstructing itself, temples were left unattended. In 1972, India passed the Antiquities and Art Treasure Act, banning the trading of artefacts made a century ago.

However, in Tamil Nadu, it was only in the 80s that the government started taking serious note of idol thefts, particularly under the MG Ramachandran (MGR) regime, which was said to be more pious, and tried to retrieve some idols.

The first instance was in 1982, when the state government recovered idols, including a Nataraja unearthed from Thanjavur in 1976, which were smuggled to London. All thanks to Dr R Nagaswamy, the then-director of archaeology department.

Since then, idols have been traced to some country occasionally. According to HR&CE data, between 1992 and 2017, 1,204 idols were stolen from 387 temples and 56 were retrieved till 2017.

Archives and its service

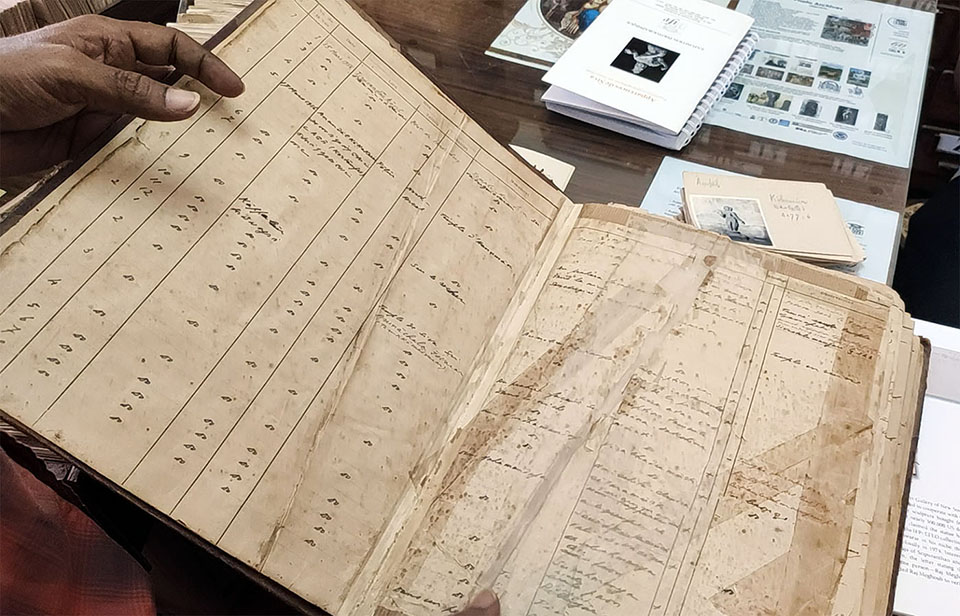

The French Institute of Pondicherry (IFP) was established in 1955, a year after the French territory was merged with the Indian Union. Dr Jean Filliozat, its first director, along with member NR Bhatt, initiated the studying of Saiva Agamas. Today, there are about 8,000 bundles of Agama scripts, thanks to this initiative.

To complement the study, Filliozat started a project to document temples and idols with the aid of photography. That initiative has resulted in the 1.7 lakh archive photographs.

“This vast database was possible because of the researchers. During the initial years, many PhD students from France came to Puducherry and researched about south Indian temples and photographers went with them. Over a period, it was decided to document popular temples through some funded projects. And that is how the archive was built," says Kumar, who has been working at the institute for more than 25 years.

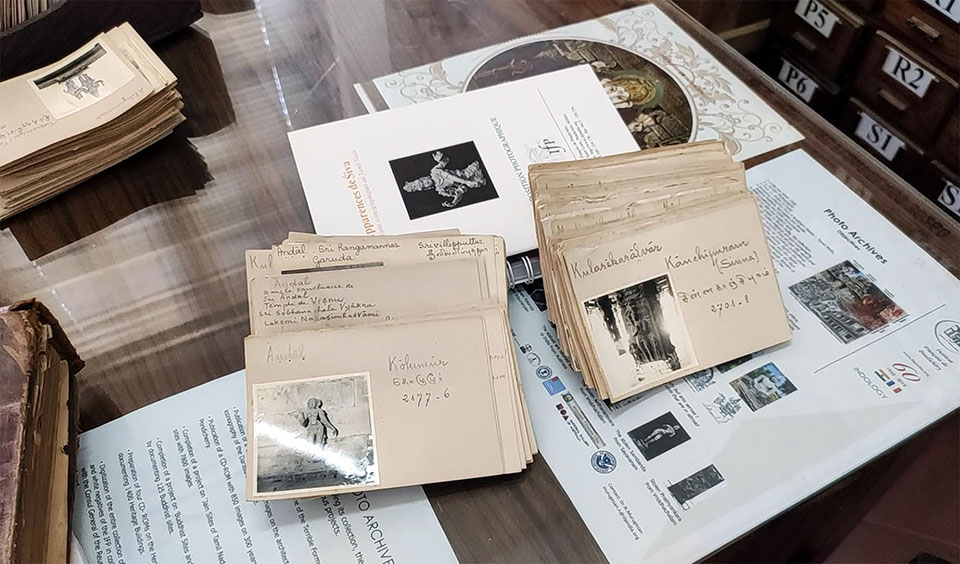

The photos are categorised as 'Sites' and 'Subjects'. Back then, the date, name of the researcher and the name of the temple were entered manually in a register. The negatives were developed and pasted in a 6x6 index card along with information like name of the idol, date when the image was taken, reference number, etc. Those index cards along with negatives are still protected in wooden drawers.

Modus Operandi

The masterminds of idol theft have two names —Subash Kapoor, a New York-based Indian-born American art dealer, and Sanjivi Asokan, a Chennai-based art dealer.

In his book Shadows of Gods, Sricandane says Kapoor met Asokan in 2006 in Chennai and introduced him to the international market for stolen idols. It is said that even before meeting Kapoor, Asokan had tried his hands at idol theft in a small way.

Since Asokan has a good knowledge of Tamil Nadu, he had an idea of ancient temples and idols, which were left unattended.

"As the first batch of stolen bronzes reached Asokan, he got replicas made. The originals were then mixed with replicas and sent to the Assistant Director, Handicrafts Development office of the Ministry of Textiles to obtain certificates declaring them as artistic handicraft products,” writes Sricandane in his book.

By getting the idols tagged as handicraft products, they were able to bypass the idol trade ban and export them to New York via London, where Kapoor would get another certificate from an organisation called 'Art Lost Register' which would say that the particular product is not a stolen one.

Identification process

When an idol is found as duplicate, two cases are filed. One saying the idol that is kept in the temple is a duplicate and two, that the original was stolen.

When police come across a suspected case of theft, they approach institute with the details — that could include a photograph, temple or idol name — which are mostly poor.

"The police bring a photo which is captured in a poor light. Most of the times, the idol would have lost some of its body parts, jewellery or tools. It increases the confusion. Sometimes they know the idol's or the temple's name,” says Kumar.

“We compare the idol with every photo we have. We then analyse each and every part of the idol in the picture and decide whether the idol is an original or duplicate," he says.

Case studies

During a routine vehicle check in 2008, Kerala police caught Pitchaimani, Marisamy and Sriram — all Asokan's aides — with a Ganesha idol that they were smuggling from a temple in Suthamalli village in Ariyalur district.

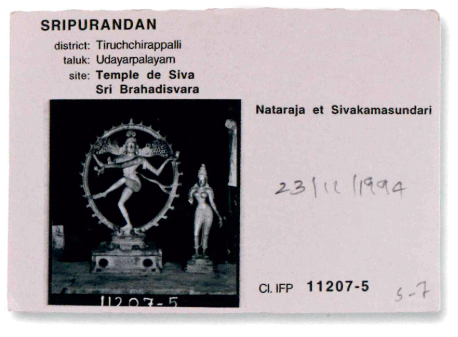

The investigation led to another major idol theft — that of a life-size Nataraja idol from a 9th century Brihadishwarar temple in neighbouring Sripuranthan in 2006. With Asokan’s help, Kapoor had stolen the idol and used a fake document claiming the idol was out of India since 1971 (as the law to ban idol trade came into force in 1972), to sell it abroad.

HR&CE officials realised the theft only in 2008 when they planned to install an iron gate for the temple. By then, the idol had reached the National Gallery of Australia (NGA).

The police then did not have a clue about the idol, especially since HR&CE did not allow photography and photo evidence was lacking. And they didn’t know about the French Institute’s archives.

Case study 1

Idol: Nataraja

Location: Sripuranthan, Ariyalur

Status: Retrieved

Image of Nataraja from IFP-EFEO archive

Image of Nataraja from the Australian museum

The Nataraja idol was stolen from a temple in Sripuranthan, Ariyalur, and was traced to the National Gallery of Australia (NGA). On establishment of identification, Australian government returned the idol to India, with its Prime Minister Tony Abbott himself handing over the idol to his Indian counterpart. Due to security reasons, the idol is now kept in a Tamil Nadu government safe-house in Kumbakonam.

When they went to Sripuranthan, locals told them that some people from the institute had taken photographs around 1994. Soon, the cops landed at Puducherry where the institute’s officials immediately dug out the photographs.

Interestingly, these photographs established that the document prepared by Kapoor claiming that the idol was out of India since 1971, was fake. But the Australian authorities were hesitant to accept this.

Moreover, after stealing the idol, Kapoor removed some features of the idol such as the pedestal, and then took another photo of that idol. He also changed the colour of the idol and sold it to the National Gallery of Australia (NGA). There the idol was photographed again. During investigation, when all the three photos of the idol were compared, almost seven features matched with the photo taken by IFP. The NGA had no other go and returned the idol in September 2014, which came to a rousing reception in Tamil Nadu.

Case study 2

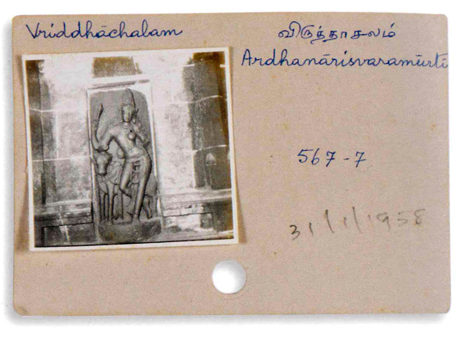

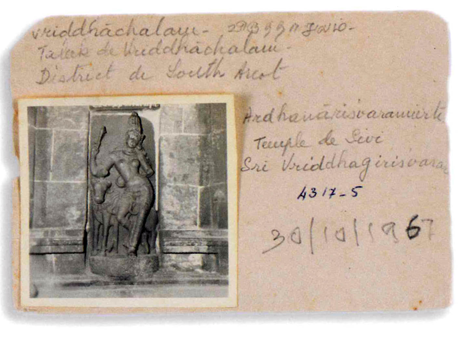

Idol: Ardhanarishwarar

Location: Virudachalam, Cuddalore

Status: Retrieved

The idol of Ardhanarishwarar (half-male Shiva and half-female, Parvathy) was stolen from Virudachalam and exhibited at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. It has now been returned to India. The IFP/EFEO had photographed the idol thrice in 1958, 1967 and 1974, which helped to prove that the idol was not stolen before 1971.

Similar photo evidence played a role in retrieving the Ardhanarishwarar idol from the Art Gallery of New South Wales. The idol was stolen from a temple in Virudhachalam in Cuddalore district. The documents prepared by Kapoor said that the idols were out of India since 1971. But interestingly the IFP had photographed the idol in 1958, 1967 and 1974, which busted his claim.

The recent investigations into the Tirumangai Alwar too followed the same modus operandi. In this case, the IFP was able to establish, after detailed examination, that the idol kept in the Kumbakonam temple was a duplicate.

Also read: Thirumangai Alwar idol in Kumbakonam temple a duplicate. Here’s why

For example, in the crown of the idol, the curvature is different as compared to the original. Also the eyebrows in the replica were drawn crudely. In the original idol, the sacred thread pass above the navel, whereas in the duplicate, it passes by the side of the navel. And there are quite a few changes in the cloth on the lower part of the body, especially the width of the strip and its uneven height.

Case study 3

Idol: Thirumangai Alwar

Location: Kumbakonam, Thanjavur

Status: In the process of retrieving

Image of Thirumangai Alwar from IFP-EFEO archive

The idol currently in posession with Ashmolean Museum

The Idol presently at Kumbakonam temple

Index cards, sized 6x6” have names of the researcher, temple, idol along with a small photo of the idol.

Scope for improvement

Frederic Landy, director, IFP, tells The Federal that France has taken an initiative of returning the artefacts to the respective countries.

"When the French colonised many parts of the world, including African countries, it had taken some antiquities like idols from churches. But after the end of colonisation and the countries became independent, France decided to either return the antiquities to the respective countries or to maintain them well. Many African countries asked the French government to keep some antiquities with them,” he says.

This is because many of the antiquities have lost their importance of being worshipped. So, stealing such idols now does not have any impact. “But that is not the case with India,” Landy stresses. “Here, each and every idol still has the capacity of being worshipped and that is why many steal the idols.”

Landy says the process of retrieving idols can be improved but given the number of temples in the state and the shortage of manpower and money, it has practical difficulties.

Kumar too underlines this aspect. “If we have more funds, we can conserve the archives in a better way.”

On why recoveries are not done government-to-government, Sricandane says in many cases, museums of international repute did not do their due diligence in checking the provenance of the artefacts that they were buying from dealers.

In some cases, however, he says governments do exchange, sell or offer cultural artefacts to other countries.

Kumar notes that nations want to showcase that they have something valuable from history and that's why they are showing interest in collecting such artefacts.

Looking back, Landy notes that when the archives were established, none of the founders had thought it would be of help in such a way.

"The usage of the archives has been realised more than ever now," he says.