Unmasking a new plastic problem during COVID-19

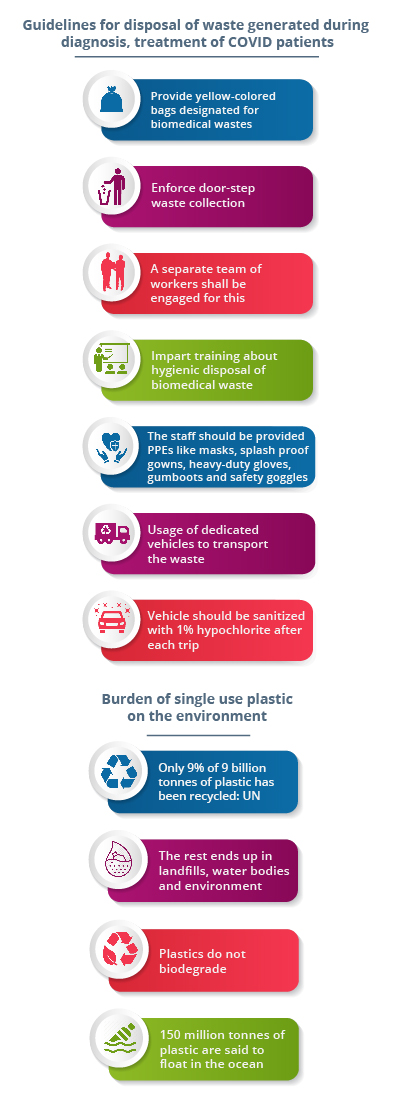

Now with the increase in movement and gradual unlocking of the country, the problem of non-biodegradable plastic is back to haunt the environment, in the form of disposable masks.

A month after the lockdown was imposed in India to battle COVID-19, a sweeping change was noticed—in the absence of vehicular movement and industrial effluents, the air cleared up and water bodies purified.

However, now with the increase in movement and gradual unlocking of the country, the problem of non-biodegradable plastic is back to haunt the environment, in the form of disposable masks.

Seen as a global issue, the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) has warned that given the spike in demand for the gloves and masks post lockdown, a country like Italy would need close to one billion masks, and even if a small percentage is not recycled or disposed appropriately, 10 million of them would land in the oceans.

Closer to home, in states like Tamil Nadu, which is among the 18 states that have banned single use plastic with effect from January 2019, the plastic challenge remains. The concern regarding the rising use has triggered Ripu Daman Bevli, also known as Plogman of India, who popularised picking up litter while jogging in the country, to start a campaign on change.org against the single use surgical gloves and masks.

Cheaper options

By April, wearing a face mask was made mandatory for all, in India. Disposable masks which are relatively cheaper as compared to the other options have become popular even among households. While the disposable ones– non-woven and made of polypropylene– are priced at ₹3-4 per piece, the cloth ones cost ₹30 per piece. The demand for disposable masks is set to increase, with people beginning to travel in cities for work and errands, amid talks of learning to live with COVID-19.

Environmental activists observe that indiscriminate disposal of the masks are a big concern. Sultan Ahmed Ismail, an ecologist, says, “these will reach water bodies and landfills because there is no system in place to collect them for a uniform disposal. I have also seen some petrol stations making it compulsory for customers to wear masks, if not they are made to pay ₹5 to get one. This makes it all the more easy for them to avail them and use them more often. They add to the garbage woes and become potential carriers of infections.”

In fact, the gradual increase of its usage, triggered Jawahar Shanmugham, a Chennai-based public interest litigant and social activist to take it up with the authorities. He says that while he was assured that separate collection mechanism would be in place for them, on the ground, little has happened.

RELATED NEWS: Coronavirus lasts on face masks for a week, currency for days: Study

“These come under bio medical waste and have to be disposed of in the ways prescribed under Bio Medical Waste Management Rules. We have these coming from the quarantine centres and households, apart from hospitals. Even for the bio medical waste generated in hospitals in Tamil Nadu, there are just two treatment plants for five districts— Chennai, Cuddalore, Chengalpattu, Kancheepuram and Tiruvallur. Now, the added waste from households will be landing in the corporation dustbins, increasing the risk of spread of the disease through the disposed masks”, he adds.

More protective than cloth

The exemption given to non-woven and polypropylene in Tamil Nadu for medical goods has kickstarted several factories that closed due to the ban on single use plastics last year in the state, points out S Rakkappan President, Tamil Nadu Plastic Manufacturers Association.

He says, “these masks give a better protection from the spread of virus because they do not allow the air to escape. However, they cannot be used more than once and bring a lot of concerns about waste management.” He points out that while allowing its use, the government should also have come up with a concrete plan for waste management.

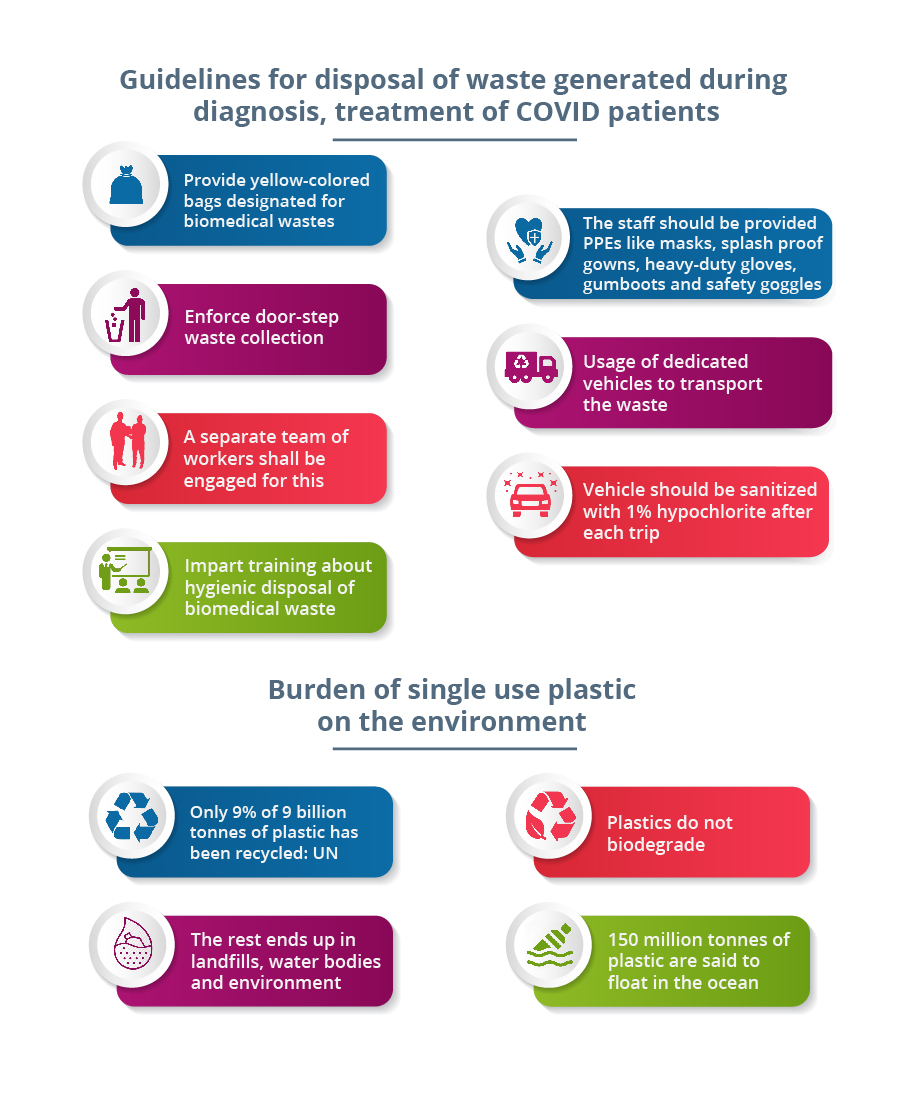

Urban local bodies like Greater Chennai Corporation has been following the guidelines issued by the Central Pollution Control Board, regarding the collection of used gloves and masks in yellow bags through authorised waste collectors.

N Mahesan, Chief Engineer, Solid Waste Management, Greater Chennai Corporation, says, “we have been sending in teams to collect the gloves and masks from those in quarantine and containment areas, every day. These are sent to the incinerator in Manali. The team is equipped to collect them, donning PPE. However, we are unable to keep a tab on the usage of single use masks in common households,” he adds.

A movement that tries to make a difference

Amid the scramble to buy disposable masks, Namma Ooru Foundation, an organisation based in Chennai, batting for the environment is on a mission to reach out to at least 10,000 people with 20,000 cloth masks. P Natarajan, founder and chief volunteer of the organisation, explains that they have been crowd sourcing cloth from citizens to make these masks by a tailor who is also getting an opportunity to earn income.

He adds, “the masks used by COVID-19 patients and their caregivers are supposed to be soaked in a bleach and buried in a pit dug deep or burnt, in order to dispose them. But many are not aware of this and are continuing to use them, even as we have a solid waste management system that is ineffective not just in Chennai but across India. There is no infrastructure available as a standard operating procedure for their disposal. The disposable masks are being handled by sanitary workers and rag pickers, who are directly exposed to the perils of infected masks.”

RELATED NEWS: COVID-19: Govt asks people to wear homemade face masks

Ganga Sridhar, who is part of Eco-Konnectors a group creating awareness on the bane of plastic and to adopt greener practices in Chennai, says that promoting cloth masks are also a part of the government’s duties.

“There are PDS outlets distributing these masks to the people, who come there to collect their monthly ration. That is a good sign for things to come and can ensure that people stick to cloth options,” she adds. “Those who use disposable masks in the hospital set ups are aware of ways to dispose them. Moreover, over dependence on disposable masks could result in a shortage for those who need it—like the frontline healthcare workers.”

Ismail bats for alternatives to be made available at a cheaper rate. “If pricing is the issue, we must have alternatives that are reasonably priced to ensure that we do not flood our water bodies or soil with these masks.”